Dementia simulator: My experience of the Virtual Dementia Tour

All that I could hear was static and haze. All that I could see were dark outlines, with occasional flashes of strobe lighting. All that I could feel were my poor feet suffering from the worst pins and needles I have ever experienced. I truly had stepped into the shoes of someone with dementia.

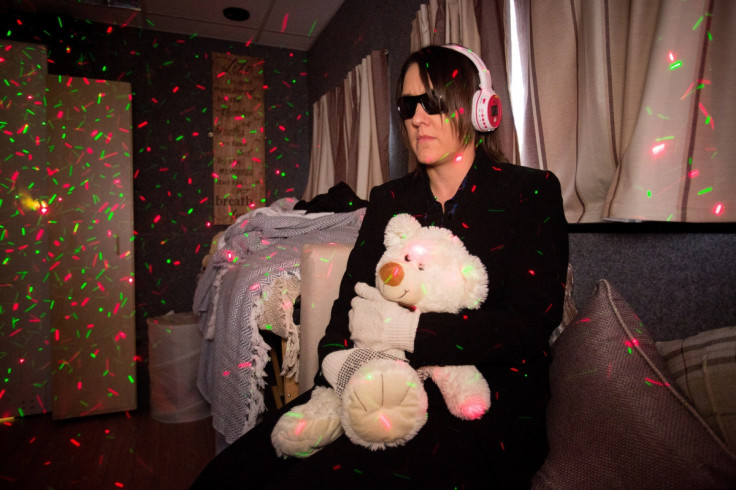

The Virtual Dementia Tour was designed to not just show people what it is like to have dementia, but also to sense it. With large headphones covering my ears, blasting out all kinds of noises – from loud sirens, to alarm clocks – and makeshift sunglasses with the central vision distorted, it was a hard-hitting experience.

Invited along to Abbeyfield residential care home for dementia patients, I was admittedly a little sceptical about how someone could truly experience what it is like to have the neurological condition; albeit slightly nervous at the same time.

The simulator had been taken to New Malden, south west London. It is one of just three mobile-simulators, which scientists have begun touring the country with in attempt to change perceptions to dementia.

The Tardis-like mobile home was already stationed outside of the care residence on my arrival, complete with balloons and a slightly intimidating zipped-up annex. I was ushered in, and spoken at quickly, yet firmly, about what I may experience in the next room.

I was told to place spiky in-soles into my shoes (so that the weight of my body presses my feet right down onto the hard surface), and then put on glasses, gardening gloves and bulky headphones. Without any other words, somebody flicked a switch on my headphones and I was shepherded in to the next room.

The first thing that hit me was the noise. Screeching, yelling, pounding, banging; basically all of the –ing's. It was enough to confuse all of my senses alone, as it became apparent dementia patients endure this torment every day.

Next came the darkness. All of the curtains were shut, my sunglasses shaded the little remaining natural light, and every now and then I would get green or red nightclub-esque strobe lights hit me right in the eye – and in that darkness, it felt as if it were being physically pressed against my optical nerve there and then.

While I was struggling to comprehend what I was actually experiencing, a faint shadow of a human outline stood in front of me and read a list of chores for me to complete. In my dazed state, I picked up maybe one or two of these tasks out of a possible eight or so – write a letter and put it in an envelope, and set a table for four. I asked the shadow to repeat itself so I could catch the other bits, but it just stared back at me without responding.

I wandered over to a table after standing in the same spot for a good 20 seconds – trying to think about my next move. Trying to write a letter – with handwriting a four year old could rival – I failed to fold the paper into an envelope. It must have been obvious that I was getting frustrated, because the shadow re-emerged from behind me, and shouted at me: "Find something useful to do."

All that I could do was apologise, and feel that I was wasting people's time by being so useless. I began to panic, and did not know what to do next – just as an ear-shattering police car decided to drive past in my headphones.

After the seven longest minutes of my life the ordeal was over, and I was grateful to take off my headphones and sunglasses to view the room I was standing in. It looked like any other normal studio flat (just built into a mobile home), and it was difficult to believe that this was the same place that I had been wandering about aimlessly, trying to find a piece of paper.

PK Beville designed the simulator in 2001, with the hope that the public could experience the difficulties of living with dementia. This does not just include trying to move around and carry out everyday tasks, but it shows how some dementia patients are treated, as the impatience of the human shadow serves as a model for some family members and carers.

Beville said that unlike some people who create these types of revolutionary idea, she did not have any personal experience that led her to create the simulator. It was purely out of frustration of seeing no changes in the behaviour towards dementia patients.

"I tried interactive videos, I tried role-playing, I tried everything I possibly could and nothing was changing," said Beville. "I even gave key note speeches, and at the end I would physically transform into an elderly woman with dementia. I'd get the obligatory standing ovations, and then they'd go straight out and do the same things that I was trying to tell them not to do.

"I'm hoping here towards the end of my career, that this is something that will live long past me and [help] make some major changes."

As the only dementia simulator of its kind in the UK, the team is touring the UK to try and implement these major changes, with two ultimate goals; engaging carers, family and friends with the struggle of living with dementia, and also getting the prime minister to have a go.

"We've got around 500 homes and houses across the country," said April Dobson from the Abbeyfield Society. "We'll try to group them together so the bus can park up in one location, and all of the staff can have a go. Then we'll try and get all of the members of the community to have a go as well, and family members which is really, really important."

Dementia currently affects around 850,000 people in the UK – one in six in the over-80s. With the sad reality that a cure any time soon is unlikely, experts believe that instead of changing the patients themselves, it is time to change the people around them.

Dobson said: "There is no cure in sight, and that can be very disheartening for all people who are diagnosed, and their families. We want to make it more positive; so don't think it's the end of their life. The person is still there, with all the things that they bring, all of their experiences and life history, they're still that person, and we have to see through the condition."

The Virtual Dementia Tour certainly changed my perception of how to treat patients. If everybody could experience it, I am sure the nationwide attitude towards dementia would improve, and Beville will finally realise her dream.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.