Dinosaur-Destroying Meteorite 'Pushed Reset Button' On Forests

The famed meteorite that ended the age of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago restructured our forests and gave us the trees we have today, researchers believe.

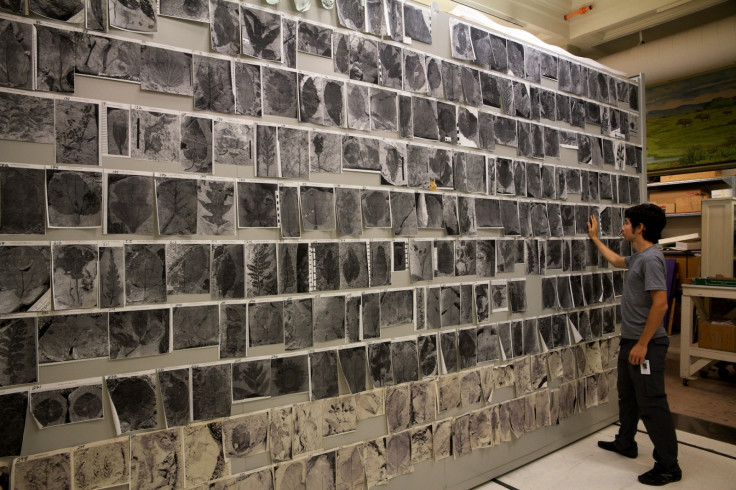

A team of scientists from the University of Arizona studied a collection of thousands of fossilised leaves from plants and found that the impact of the meteorite decimated the slow-growing evergreen species, allowing them to be replaced by the fast-growing deciduous trees.

The scientists were able to reconstruct the complex ecology of a thriving plant community over the 2.2 million years spanning the devastating meteorite impact. It is thought that this event wiped out more than half of the plant species living on Earth at the time.

This has left the world dominated by forests made of deciduous plants, and only a few with a high evergreen population.

"When you look at forests around the world today, you don't see many forests dominated by evergreen flowering plants," said the study's lead author, Benjamin Blonder. "Instead, they are dominated by deciduous species, plants that lose their leaves at some point during the year."

The 1,000 fossilised plant leaves were taken from a location in North Dakota, where they were embedded in rock layers known as the Hell Creek Formation.

By studying the leaves, researchers were able to predict how plant species used carbon and water, helping them understand the ecological strategies of plants from millions of years ago.

The mass of a leaf in relation to its area is a good indicator about how much carbon had been invested in it. The bigger the leaf, the more carbon was put into it.

The density of the leaf's vein network is used to determine how much water has moved through the leaf. The more veins there are, the more water has passed through it and the more carbon it was able to take on.

The two parameters are then compared to get an idea of the amount of resources contributed, to the amount that were put back out.

Evergreen plants are more likely to raise leaves which require a lot of carbon and water, but last a long time, whereas deciduous plants use a lot less with a higher metabolic rate and a shorter life-span.

As the deciduous plants are faster growing and require less resources, scientists believe this enabled them to beat out the evergreen species.

Evolutionary Theory

Although it was known that there was a great shift in the plant species of the world from before to after the impact, there has not been much evidence on how the event affected plant communities at the time.

The two theories, according to Blonder, are that either the meteorite that hit the Earth was like a reset button which killed off all species, or that some species had special traits which allowed them to survive and flourish where the others had died off.

"Our study provides evidence of a dramatic shift from slow-growing plants to fast-growing species," he said. "This tells us that the extinction was not random, and the way in which a plant acquires resources predicts how it can respond to a major disturbance. And potentially this also tells us why we find that modern forests are generally deciduous and not evergreen."

Previously, scientists found that dust from the impact caused a dramatic drop in temperature, or 'impact winter'. Many plants would have struggled to thrive in this environment due to the lack of sunlight to promote their metabolism and growth.

"The hypothesis is that the impact winter introduced a very variable climate," Blonder said. "That would have favoured plants that grew quickly and could take advantage of changing conditions, such as deciduous plants."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.