Emotional scenes as relatives who fled Mosul separately are reunited at refugee camp

Relatives hold hands and try to embrace through the wire fence around the camp, lifting up new babies so that their families can meet them.

The wire fence around an Iraqi refugee camp has become the scene of many emotional reunions between family members who fled Mosul separately. Relatives hold hands and try to embrace through the fence, lifting up new babies so that their families can meet them. For some, this is the first time they have seen their loved ones in more than two years.

More than 70,000 people have left Mosul since the campaign to retake the city from Isis began. Most of the residents escaping through the east side of the city are being held temporarily at the government-run Khazer camp, home to almost 30,000 people. Authorities require fleeing civilians to stay in camps even if they have family outside, so that males can be checked for ties to Islamic State (Isis/Daesh).

Family members who got out just in time before Isis took over Mosul in 2014, gather at the fence around the camp, impatient for the new arrivals to be released.

Winter has brought freezing temperatures, so concerned relatives have been bringing blankets and pillows. "My relatives have ice on their tent at night," a man named Salah told Reuters, as he waited for his cousins and their five children to pick up the bags. "They don't get enough blankets so I brought them from my house." Soldiers only occasionally open the gate to allow civilians to bring supplies to relatives inside.

The camps set up for people fleeing Mosul have basic facilities. Tent are often equipped with solar-powered lamps and sockets that can recharge mobile phones and other electronic devices. Expecting a longer stay as the battle drags on, many families bring in stoves and kitchen utensils. While women of the family cook meals, men and children fetch water and bring it over to their respective tents. The international aid supply trucks arrive around noon every day with food.

The tents are often decorated with the few possessions the refugees could carry, reminders of life before the violence.

Many parents register their children to attend schools inside the camps, often their first opportunity for regular schooling in years. "Children lost two years because schools were closed under Daesh or taught only Islamic law," a teacher who gave his name as Ali told Reuters.

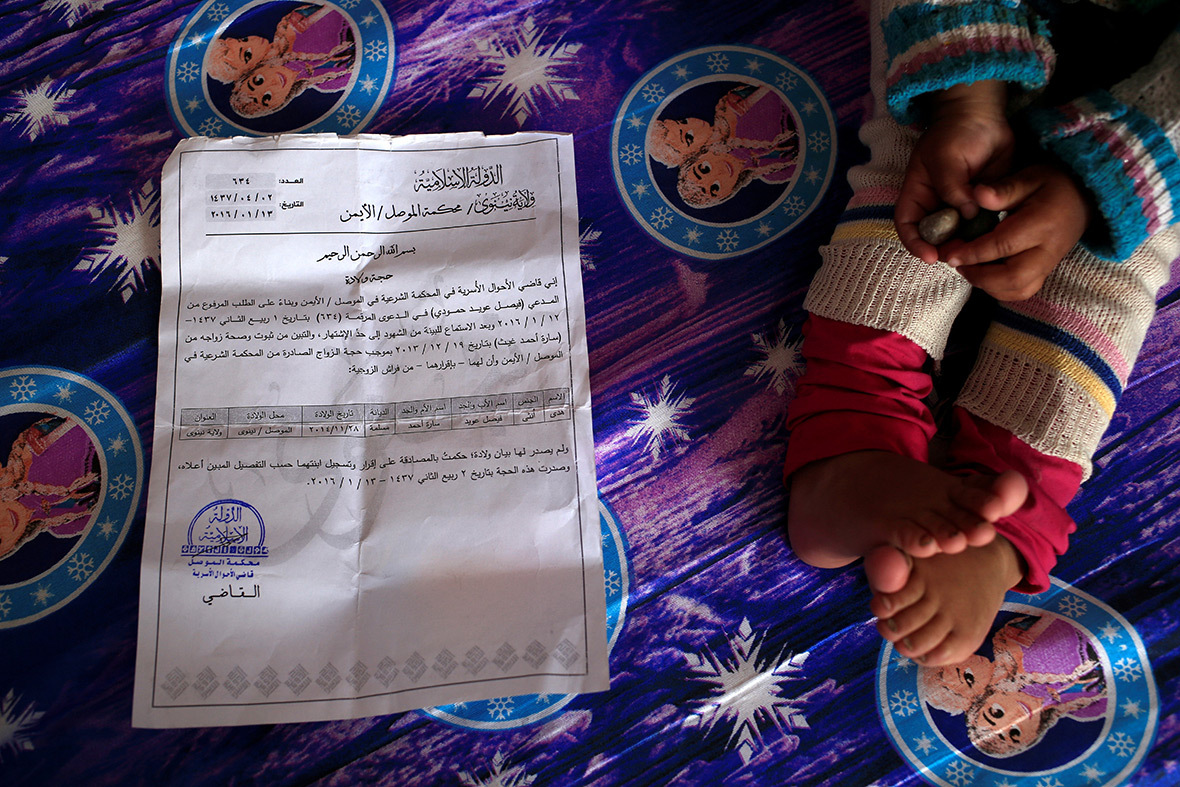

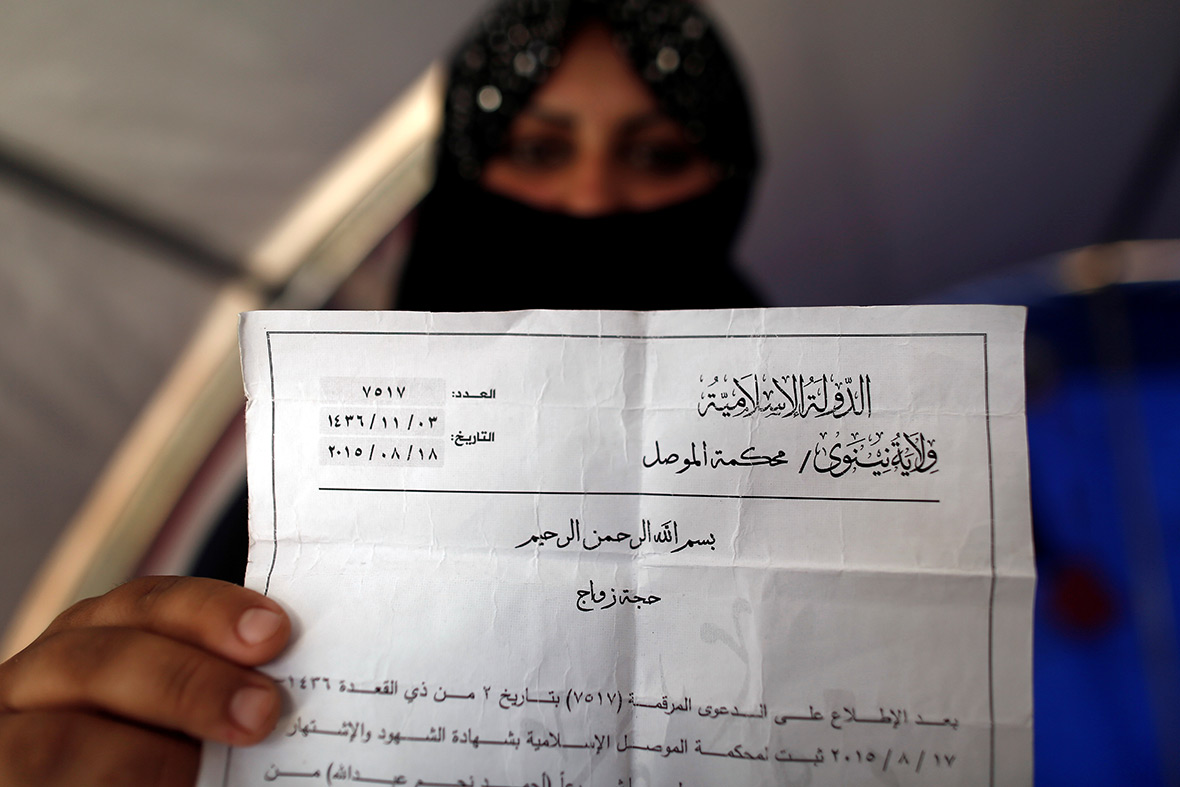

Some of the youngest children in the camp have no identity documents because births in Islamic State-controlled areas were registered with authorities that are not considered valid outside the shrinking territory – or not registered at all. There are hundreds and perhaps thousands of children across the Middle East under the age of two-and-a-half who are stateless – lacking legal recognition as a citizen of any country.

Iraqi officials are anticipating a surge in the number of displaced residents fleeing Mosul once the street battles expand from the east bank of the Tigris to the more populated west bank. The United Nations has warned that the Mosul offensive could trigger a humanitarian crisis and a possible refugee exodus, with up to one million people fleeing the city.

Visit the International Business Times UK Pictures page to see our latest picture galleries.

More from IBTimes UK

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.