Before Google Earth: First Nasa Satellite Images of Europe and Arctic from Space Unearthed

Two scientists from the University of Colorado (CU) have discovered important long-lost 50-year-old polar satellite images from Nasa's Nimbus 1 satellite, the first ever Earth observation mission which operated from 1964-1974.

After a tremendous amount of effort analysing "dark data", ie information that is stuck in an unusable format, the scientists have found the oldest ever photo of Europe taken from space, showing the Aral Sea drainage basin between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan before the water dried up.

They have also found the largest and the smallest Antarctic sea ice extent ever recorded in 1964 and 1965, as well as the earliest sea ice maximum from 1968, according to the Barents Observer.

David Gallaher works as a technical services manager in the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), which is part of CU's Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, studying data shot over a long series of time in order to understand more about how the Earth's climate changes.

In 2009, he stumbled across a Nasa conference poster stating that the old film from the Nimbus 1 had been found in a secure storage facility in North Carolina.

Gallaher began wondering if the old film might contain records of Arctic sea ice earlier than 1978, which is the earliest known full record of the northern hemisphere in existence.

Searching through tonnes of old footage

While the film had been found, no one had ever sorted through it, so Gallaher was told that he would have to sort through it himself, and a huge pallet of 25 boxes containing several thousand reels of 35-millimetre film and data tapes were delivered to the NSIDC from the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC).

"There were 50 cardboard boxes. Each contained 10 rusty, dusty canisters, each containing 500 feet of 35-millimetre negative film," said Gallaher. "We really wanted these."

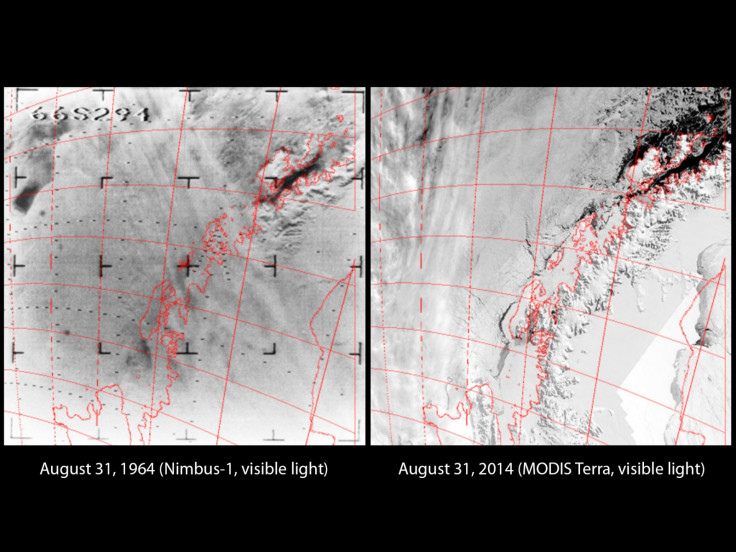

Gallaher and his colleague Garrett Campbell have spent two years digitising over 750,000 long-lost images, which weren't even originals – in 1964, Nasa's scientists had had to use the complicated and primitive method of playing the satellite footage on a TV monitor and then taking photos of the TV monitor with the data displayed on it.

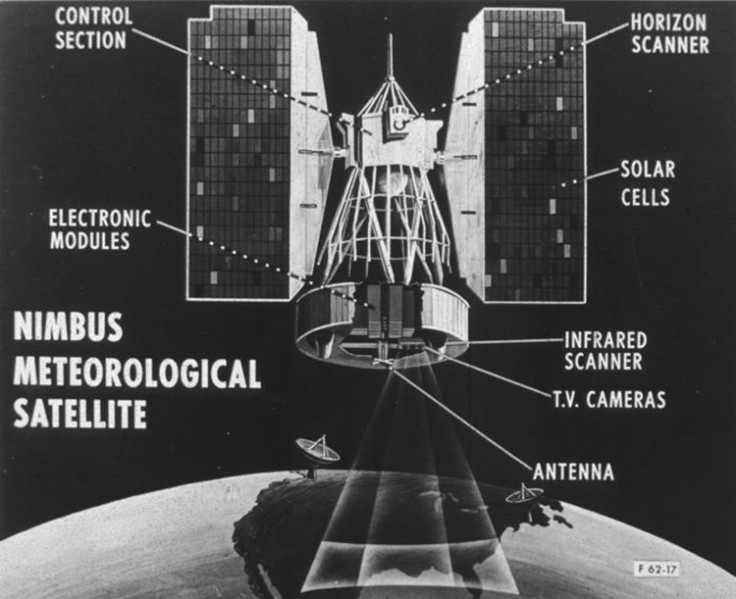

"There were no fancy satellite sensors in 1964," he said. "Scientists strapped a video camera to the Nimbus 1 satellite, sent it into orbit, and hoped for the best."

Digitising the data for a new generation of scientists

A Canadian video production company rescued and converted the film rolls containing infrared data, while Gallaher had to print out visible light images from the many negatives.

Then, with two undergraduate students, Gallaher scanned all the images into the computer at close to 40,000 frames.

They checked that all of the images had the correct latitude and longitude, and then stitched the images together using an image editing program on computers to produce full satellite maps of the 1964 data.

"In 1964, researchers would have had to develop every single frame as a photograph and lay it out on the floor of a large room," said Gallaher.

The original cost of sending the Nimbus 1 satellite into space in the sixties and the project to analyse its data cost tax-payers billions of US dollars, but the whole project to retrieve the data has cost much less and fits onto a tiny memory stick.

Best of all, Nasa has decided to release all the satellite data for free on the NSIDC website, so scientists all around the world can use it in their research to answer important questions about climate change and deforestation.

Gallaher now hopes to set up a company to retrieve more dark data, if he can obtain enough funds.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.