Gamechangers: 'Stressful and dangerous' conventional IVF should be abandoned, says Dr Geeta Nargund

Dr Geeta Nargund is uncompromising. She wants an end to Conventional IVF.

To meet Dr Geeta Nargund you go into the basement of a glass office block at St Paul's, London and enter what looks like a dentist's waiting room. Less high-end spa, more the sensible practicality of the NHS, the reception has three extremely anxious looking couples waiting and fidgeting.

They glance up at me - 40 years old and the only person alone - with silent curiosity and I am surprised and ashamed to admit the desire to shout "No, no, I'm a journalist, I have three kids". The realisation of the dark secrecy of infertility winds me. No one wants to need this help.

I pop to the loo where the sign on the door says 'Please do not empty your bladder before embryo transfer or endometrial scratching'. Bloody hell, no wonder they look nervous.

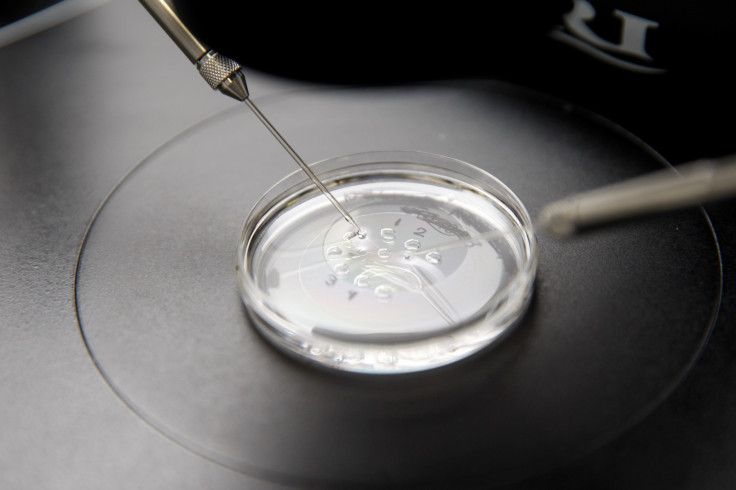

Nargund arrives late and flustered by delayed trains. She talks passionately and at helter-skelter pace. "Conventional IVF involves the shutting down of ovarian hormones followed by higher doses of drug stimulation. This approach is outdated and should be abandoned as safer, healthier alternatives now exist," she announces emphatically. I am so surprised I check she has actually said this.

Harsh sacrifices

"Yes, it is too stressful physically, emotionally and financially", Nargund continues. For every 50 cycles, one woman can be admitted to hospital due to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Although rare, it is potentially life-threatening. Some women can die if they develop severe OHSS: "It is unacceptable that women should risk life just as we try to create it."

As a junior doctor in the late 1980s she was part of the team that introduced the first IVF clinic in Ireland. Since then she has worked in a number of hospitals around the world before becoming at consultant at St George's Hospital, London.

Her work is motivated by her desire to help people have children but she talks less of babies; she is more interested in the women she is treating. She explains that men don't suffer during infertility treatment like women do, injecting themselves while at work, going through forced menopause followed by the over-stimulation of ovaries.

She clearly relates strongly to the struggles of her patients. She speaks of women who have had to give up their jobs to cope with the treatment - meanwhile needing those jobs to be able to afford to do it.

A gentler approach

Her step forward is informed by something I hadn't realised: women's bodies know which the healthiest eggs are and they get the advantage in the race to conception. One problem with traditional IVF is that, while you get lots eggs, they may not be the best quality ones.

Implantation from cycles where a high number of eggs - more than 15 - are collected can lead to the risk of lower birth weights and ongoing health problems. But Nargund is changing that. She has worked out how to identify healthy eggs with good blood flow.

She has conducted research and published papers on her findings and honed her attention on a more natural, gentler form of IVF. Her approach is also cheaper than traditional methods – coming in at around £6,450 for three cycles plus a few extras.

Her energy rises dramatically when she talks about hosting annual meetings to share her research. She is very proud that "the father of IVF" Bob Edwards congratulated her on her work and opened her first annual congress on the subject.

As we come to a close, I admit I have a burning question, which I suspect is not the one you're supposed to ask. "The people who come to see you, the ones who have no medical explanation for their problems... are they having enough sex?"

I half expect a bollocking about the seriousness of fertility issues. But she smiles: "It's hard to say. Sometimes they've been trying for a year. But when I question more they admit that they have only tried during ovulation in four of the 12 months." She sighs. "They may well not be having enough sex but many of them are working against the clock. We must try for them."

I leave in no doubt that Nargund is striving for the very best for her patients. I reflect on the determination it takes to challenge the medical establishment: thank goodness she is up for the fight.

Christine Armstrong is a contributing editor of Management Today, author of Power Mums (interviews with high-profile mothers) and founder of www.villas4kids.com

She can be found on Twitter at @hannisarmstrong

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.