Gas Hydrate: China to Start Commercial Production of 'Flammable Ice' by 2030

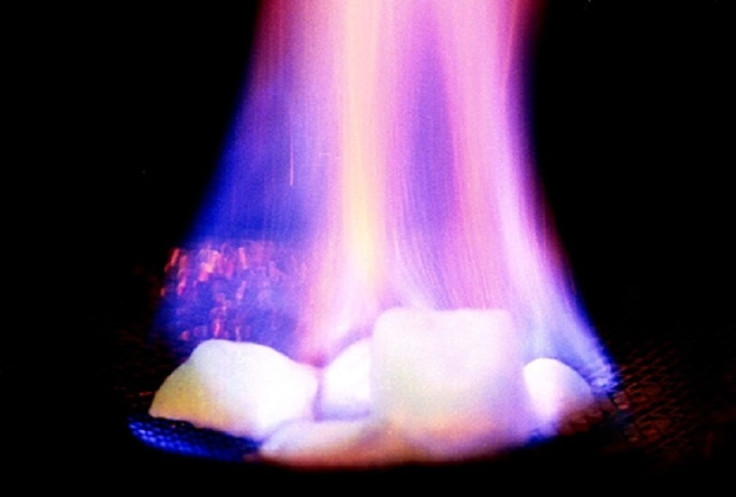

China is set to begin producing 'flammable ice', an unconventional untapped energy source found in permafrost and ocean sediment.

According to the Xinhua news agency, the nation will begin commercial production of gas hydrate by 2030.

Gas hydrate, or flammable ice, is ice crystals with methane gas locked inside. It is formed under high pressure and low temperatures. In China, it can be found in the Qilian Mountains, Qinghai province, as well as beneath the South China Sea.

When it is exposed to normal air pressure, the substance expands up to 164 times its volume, providing natural gas – a cleaner energy source than carbon dioxide – and water. However, the environmental impact of such a process is unknown.

It is estimated that China has the equivalent of 110 billion tonnes of oil in gas hydrate. Li Jinfa, deputy director of China Geological Survey, said the energy source will allow China to keep up with other countries in developing new energy solutions.

He said gas hydrate will change China's energy structure. Since 2010, China has been the biggest global energy consumer.

At present, no country has been able to produce gas hydrate on a commercial scale because of the difficult conditions of the gas and the risk to the environment.

China will start to increase its research and development in testing gas hydrate from 2017: "The production testing will help improve mining technology and equipment, laying the foundation for future commercial production," Li said.

He added that these exploratory tests will help provide information on the potential impact to the environment: "The sudden release of gas hydrate during improper drilling can influence the stability of seabed structures, even triggering geological disasters such as tsunamis and small earthquakes under the sea, posing severe challenges for future exploration."

In 2012, the US Geological Society addressed concerns about the use of gas hydrates, saying it is unlikely methane will become unstable and significantly increase the effects of climate change.

Speaking to the New York Times last year, Hideo Narita, the director of the research laboratory, part of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, said: "We need to know more about the physical properties of hydrates themselves, and of the sediments as well."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.