Hidden treasure trove of Osiris, Ptah and Sphinx idols discovered in Ancient Egyptian temple

The figurines were found in the temple of Ptah.

An unusual collection of statues depicting Egyptian deities and mythical creatures has been discovered in an Egyptian temple.

The collection – known as a favissa – was first unearthed by archaeologists in 2014, with the statues now being described for the first time in detail in a study in the journal Antiquity.

Favissae, which contain sacred objects in foundation trenches, are particularly rare in Egypt. This favissa includes figurines of Osiris, the god of rebirth, arranged around a central statue of Ptah, the god of craftsmanship and creation.

It was found during excavation of the temple of Ptah at the northern edge of Amun-Re in Karnak. It was discovered close behind an edifice of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Thutmosis III. The statues were found in an oval pit about 1.5m long, 1m wide and almost 1m deep.

A total of 38 objects were found in the pit, made of limestone, greywacke, copper alloy, tin-glazed pottery and ceramics. They included:

- 14 statuettes and figurines of Osiris

- Three baboon statuettes representing the god Thoth

- Two statuettes of the goddess Mut, one with hieroglyphic inscriptions

- Two unidentified statuette bases

- One head and one fragmentary statuette of the cat goddess Bastet

- One small fragmentary faience stele recording the name of the god Ptah

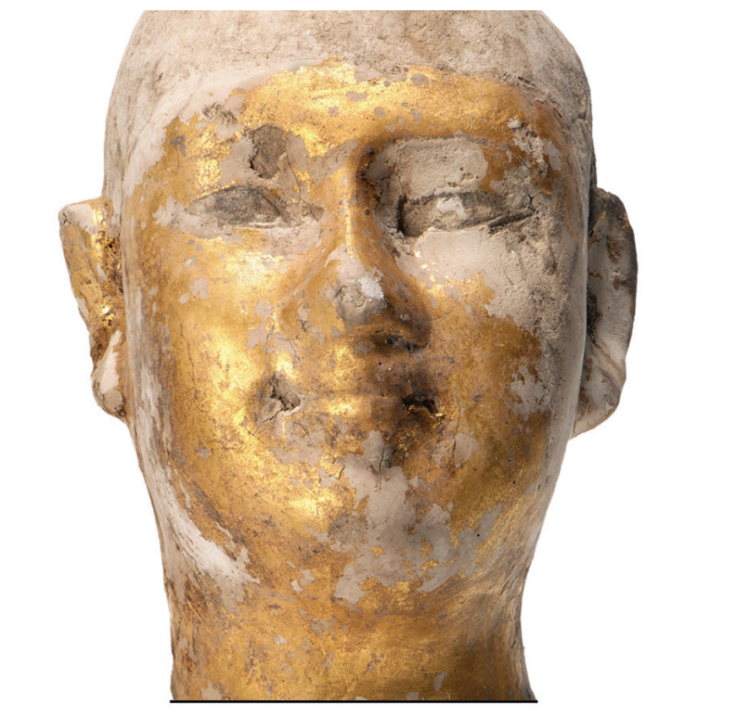

- One head of a statuette of a man in gilded limestone

- One lower part of a statue of the seated god Ptah, sawn and repaired

- One sphinx

- One unidentified piece of metal

Many of the finds were damaged by the ravages of time. But several of the statues had intricate detail preserved, allowing them to be clearly identified. It's thought that the artefacts were made between the 25th and 30th dynasties, between 760 and 343 BCE.

Although the reasons for making this deposit of statues is not known, the fact that many were broken – most likely when they were placed in the pit – suggests they reached the end of their 'lives' as ritual objects.

"This 'death' of a statue was a crucial influence in its deposition; were the breakages intended to 'channel' the energy of the statues, or to 'deactivate' their power? Or did the simple state of being broken confer eligibility for inclusion in the ritual? Current evidence is clearly insufficient to explain the raison d'être of the deposits, or to determine the intentions of the depositors," the study authors conclude.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.