HIV: Latent reservoir of virus in rare immune cells could help develop cure

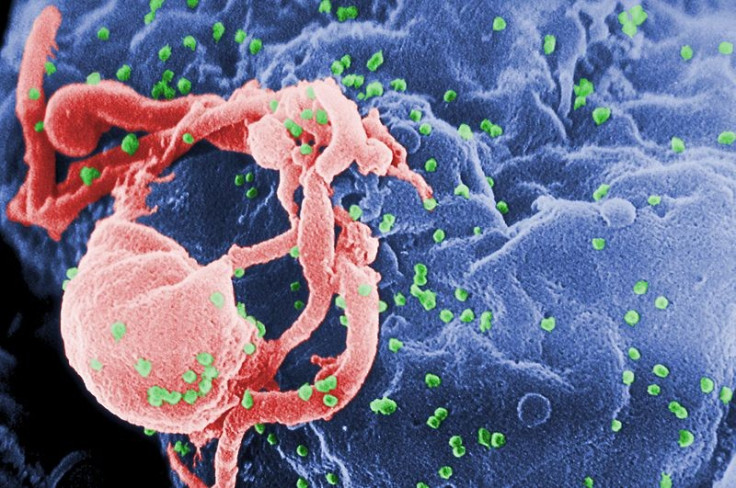

Hidden reserves of HIV viruses that lie dormant in infected white blood cells could provide the answer for a cure for the disease that has claimed over 39 million lives.

Research at Rockefeller University suggests that a quiet body of immune cells that do not divide could harbour a reserve of HIV virus, a potential target for therapies aimed at curing rather than managing the disease.

These are a type of CD4 T cells, a special kind of memory cells in the immune system that remember pathogens encountered earlier and alert the body by triggering a proliferation of T cells tuned to recognize the pathogen.

"It has recently been shown that infected white blood cells can proliferate over time, producing many clones, all containing HIV's genetic code. However, we found that these clones do not appear to harbour the latent reservoir of virus," says study author Lillian Cohn a graduate student in Nussenzweig's Laboratory of Molecular Immunology.

"Instead our analysis points to cells that have never divided as the source of the latent reservoir."

HIV belongs to a family of viruses that insert themselves directly into the host cell's genome where they linger long after the initial infection. HIV mostly targets CD4 T lymphocytes, a cell involved in initiating an immune response.

On integrating itself into the genetic code of a CD4 T cell, the virus hijacks the cell's reproductive process to produce more copies of itself which infect and kill other cells.

Most times the replication is not entirely successful but does enough damage to the immune system of the host leaving the person vulnerable to potentially fatal opportunistic infections years down the line.

Antiretroviral drugs in the market suppress HIV infection work by disrupting the host cell hijacking.

Fragment of DNA

However, a significant part of the virus remains a dormant, tiny fragment of DNA tucked within the host cell's genome. The infection remains latent.

The present study was looking for this reservoir of the virus.

Within the long human genome, the chances of the virus inserting itself in the same site are rare. Such identical cells are cloned cells while there are also the unique CD4 T cells with unique integration site.

The researchers examined cloned and unique CD4 T cells in blood samples from 13 people infected with HIV. An analytical computational technique identified the integration sites in the cells.

Tests on 75 viral sequences taken from the expanded clones of cells for dormant viruses yielded none.

This led the team to conclude that the latent reservoir resides in rare cells with unique integration sites.

The study was published in Cell.

Almost 78 million people have been infected with the HIV virus and about 39 million people have died of HIV the world over, says the World Health Organization. Almost 35 million people were living with the disease at the end of 2013 while 1.5 million died due to Aids related symptoms.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.