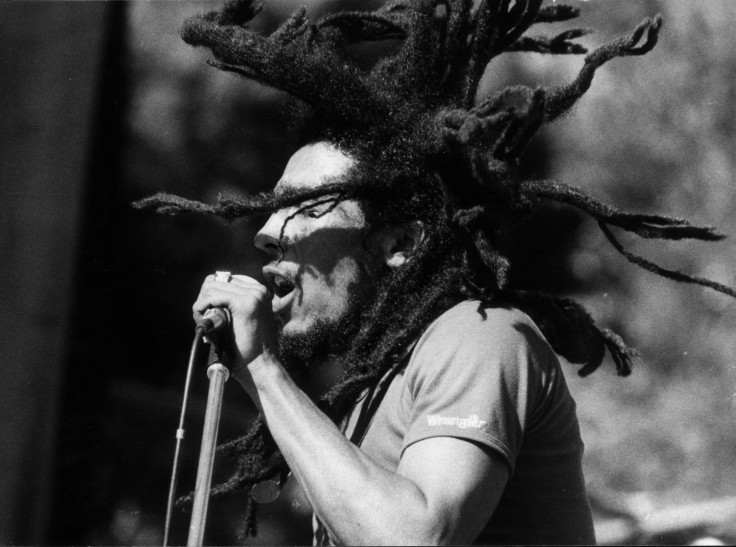

Lost Bob Marley recordings discovered in London hotel basement restored ahead of singer's birthday

The iconic reggae singer's birth anniversary is celebrated on 6 February.

More than 40 years after laying hidden away in a mouldy hotel basement in London, a collection of Bob Marley's recordings are finally getting the treatment they deserve. Discovered in a box at a property in Kensal Rise, north-west London, where Marley and The Wailers often stayed during their visits, the 13 reel-to-reel, analogue master tapes have been painstakingly restored at the White House Studios in the West of England.

"Frankly they were appalling. I almost didn't have the heart to tell the boys how bad they were because they were obviously so eager to get something off them," sound engineer Martin Nichols told BBC's Newshour.

He explained how the reels were damaged from being drenched in dirty water and had to be cleaned out inch by inch. "I wasn't too hopeful," he added.

"The end result has really surprised me, because they are now in a digital format and are very high quality. It shows the original recordings were very professionally made. From the current find of 13 tapes, 10 were restored, two were blank and one was damaged beyond repair."

The tapes feature some of Marley's original live recordings of his concerts in London and Paris between 1974 and 1978, and include songs like No Woman No Cry, Jammin, Exodus and I Shot the Sheriff.

Joe Gatt – a Marley fan got wind of the tapes from a friend and rescued them from being disposed off. "He was doing a building refuse clearance that included some discarded two-inch tapes from the 1970s. I couldn't just stand by and let these objects, damaged or not, be destroyed so I asked him not to throw them away," Gatt said according to The Guardian.

Jazz singer Louis Hoover, a friend of Gatt's then took a look at the "global artefacts" but was not optimistic of any restoration efforts. "When I saw the labels and footnotes on the tapes, I could not believe my eyes, but then I saw how severely water damaged they were," he explained. "There was literally plasticised gunk oozing from every inch and, in truth, saving the sound quality of the recordings, looked like it was going to be a hopeless task."

The restoration project cost £25,000 and Hoover compared the result to finding Vincent Van Gogh's painting equipment. "It made the hair on the back of our necks stand up and genuine shivers ran up our spines with joy," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.