Nasa's Messenger Spacecraft Reveals Mercury's Volatile Past of Ancient Volcanic Explosions

Ancient volcanic explosions rocked Mercury for a substantial portion of the planet's history, research from Nasa's Messenger spacecraft has revealed.

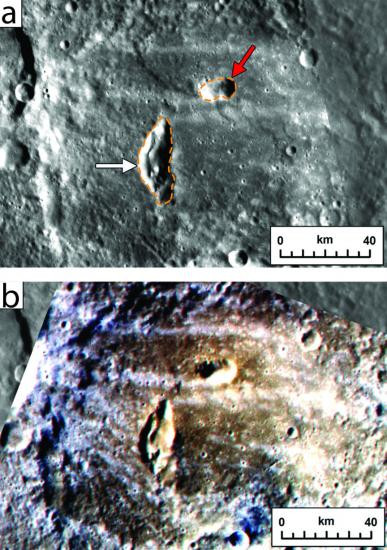

The ship, which has been orbiting the planet since 2005, has returned images of pyroclastic deposits - the telltale signature of volcanic explosions. The findings, led by researchers at Brown University, reveal how Mercury was first formed.

It was originally believed that Mercury lacked the volatile compounds that cause explosive volcanism, such as water, carbon dioxide and others with relatively low boiling points.

Tim Goudge, a graduate student from the Department of Geological Sciences at Brown, studied 51 pyroclastic sites distributed across Mercury's surface. The data was collected from Messenger's cameras and spectrometers.

The results revealed that some of the vents eroded to a much greater degree than others, indicating that the explosions occurred over a longer period, rather than a flurry of explosions early in the planet's history.

Goudge said: "If the explosions happened over a brief period and then stopped, you'd expect all the vents to be degraded by approximately the same amount. We don't see that; we see different degradation states. So the eruptions appear to have been taking place over an appreciable period of Mercury's history."

To work out a timeline of the explosions, the team examined the impact craters where most of the pyroclastic deposits are located.

The deposit has to be younger than its host crater, otherwise the it would have been destroyed by the impact that formed the crater. With this in mind, the age of the crater provides an upper limit on how old the pyroclastic deposit can be.

Results showed that the deposits were relatively young, dating between 3.5 and 1 billion years old. This finding rules out the possibility that pyroclastic activity happened shortly after the planet's formation around 4.5 billion years ago.

Goudge said: "These ages tell us that Mercury didn't degas all of its volatiles very early. It kept some of its volatiles around to more recent geological times."

The extent to which Mercury's volatiles stuck around could shed light on how the planet formed. Despite being the smallest planet in the solar system (since Pluto was demoted), Mercury has an abnormally large iron core. This led researchers to believe it was once much larger, but had outer layers removed by the heat of the Sun or in an impact.

Yet these theories have been disproved by the discovery of the volatile compounds. As traces of the substances - such as sulfur, potassium and sodium - still exist, the layers scenario seems unlikely.

Jim Head, a professor of geological sciences and Messenger mission co-investigator, explained: "Toegther with other results that suggest the Moon may have had more volatiles than previously thought, this research is revolutionising our thinking about the early history of the planets and satellites."

The research was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.