The NSA zero-day stockpile may only contain 'dozens' of vulnerabilities, researcher claims

Intelligence agencies collect unknown software vulnerabilities for their own use.

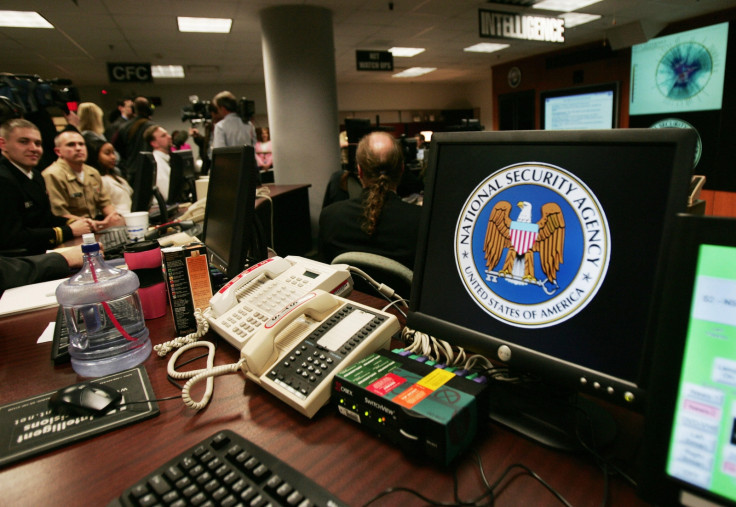

The US National Security Agency (NSA) spends millions of dollars every year stockpiling zero-day software vulnerabilities so the government can exploit them to conduct surveillance or stealthily hack into computer networks.

Yet despite public perception, especially in light of the Edward Snowden disclosures, the investment into his legally murky world may not yield as many computer flaws as many assume. That's the view of academic Jason Healey, who claims the true number of zero-days collective by the agency is in the "dozens".

Speaking during the Defcon hacking conference in Las Vegas, as reported by The Guardian, Healey – who is a senior research scholar at Columbia University – believes the NSA only adds a small number of computer flaws every year and the current rate is in "single digits".

Zero-day flaws are software security vulnerabilities that are unknown to the software vendor and can be easily exploited, often even with the most up-to-date patches installed. When security researchers, and white-hat hackers, uncover serious flaws they usually disclose their existence to the vendor so a fix can be released.

Governments and intelligence agencies, however, have other uses for them – usually under the guise of national security. The NSA itself claimed last year that over 90% of the vulnerabilities it was holding were eventually disclosed to the relevant developers. Of the other 9% at least some of those weren't disclosed because they had already been fixed by the time of release.

During his Defcon keynote, Healey asked the attendees how many vulnerabilities they believed the NSA was storing – and the results, perhaps unsurprisingly, ranged from one hundred to more than a thousand. The researcher claimed the real figure was far less in reality.

"I don't know if I have the answer, but I have got information," Healey said. "I tried to make a judgement based on my judging of evidence on technology and the policy side, and the reason we are suspicious has given us reason to research. I will not convince all of you and that is ok, what I prefer is [...] that we did the best job we could and if I got it wrong, someone can come on and give better answers."

Healey cited comments made by Michael Daniel, the US's cybersecurity coordinator, to support his assertions. In one interview with Wired from 2014, Daniel said the idea of "vast stockpiles" of vulnerabilities stored Raiders of the Lost Ark-style was "just not accurate".

He added: "The default position really is that we disclose most of the vulnerabilities that we find to the vendors. We just don't take credit for it for a variety of reasons and have no desire to take credit for it. However, later in the interview he did admit there was a "limited set" of software flaws the agency retained "in order to conduct legitimate national security intelligence and law enforcement missions".

Nevertheless, within the trove of NSA documents leaked by Edward Snowden it was revealed the agency spent $25 in 2013 to buy 'zero-day' software vulnerabilities from various "private malware vendors."

Furthermore, the NSA is not alone in its acquisition of these flaws. In one report by the Open Rights Group from 2013 – also based on analysis of the Snowden files – it was found that UK spy agency GCHQ also bought zero-days from what was described as a "thriving market."

The report said: "The NSA and GCHQ appear to make use of existing vulnerabilities in software and hardware that create risks to the wider Internet community. The agencies use any available opportunity to gather data, without a proper framework for analysing the risks and wider societal costs of their acts and omissions. Instead of clamping down on this market, security agencies and military businesses are becoming the main customers."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.