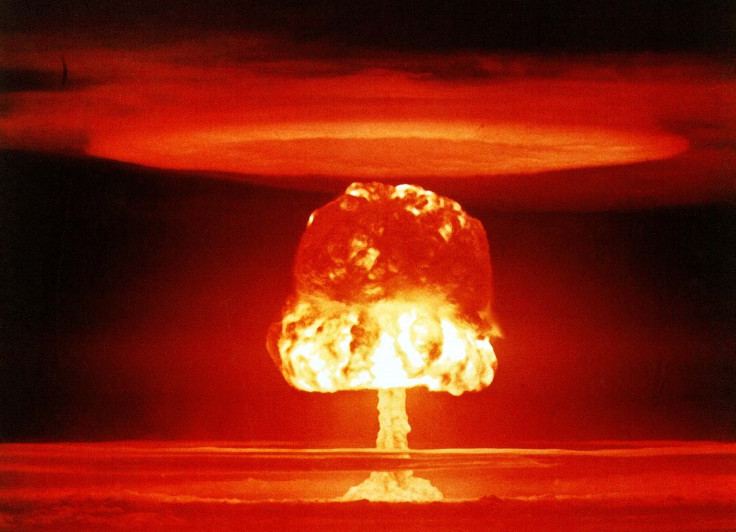

Nuclear radiation drugs offer protection up to 3 days after exposure to fallout

Drugs that can protect against the fallout from a nuclear disaster have been found to be effective up to three days after administration.

The Fukushima disaster in 2011 and the threat of radiation terrorism has highlighted the danger posed by nuclear fallout, and the need for effective drugs following exposure.

Scientists from the University of Tennessee Health Science Centre have found one drug candidate – DBIBB – protected mice effectively. Ninety-three per cent of those given the drug three days after exposure were still alive after 30 days, compared with just 20% that were not treated.

The findings, published in the Cell Press journal Chemistry & Biology, have the potential to lead to the first drug capable of treating acute radiation syndrome caused by nuclear explosions.

Senior author Gábor Tigyi told IBTimes UK that the highest radiation doses tested were 15.7 Gray (Gy). Gray is defined as the absorption of one joule of radiation by one kilogramme of matter. Normally, humans cannot survive more than three Gy.

At the Fukushima disaster, radiation at the base of the reactor was about 10 Gy.

Radiation does irreparable damage to the human body. The cells most sensitive to it are the stem cells of the bone marrow and intestine. "Radiation causes damage to the DNA and if the cell cannot effectively repair the damage done then it undergoes the process called programmed cell death," Tigyi said.

DBIBB performs three actions – it enhances the speed of DNA repair, it stalls programmed cell death and promotes cell protection and tissue regeneration.

The drug did not show any side effects in rats: "It doesn't mean there won't be side effects in non-human primates or humans – it's a huge difference in species," Tigyi noted, however.

Previously, researchers had found a molecule called lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), which is generated during the course of blood clotting, can activate the LPA2 receptor to protect against radiation induced death.

They also then found that cancer cells become resistant to radiation or chemotherapy. "If you put the two together you have something that protects the cancer cell from radiation, but it's a very active promoter of heeling, so that's why we got excited and put a drug discovery programme in place to harness this biology," he said.

"The US government showed a lot of interest because of 9/11 and radiation terrorism threat that we all face even today. There's a medical need – what happens if someone is exposed to high levels of radiation."

DBIBB is a third generation substance. The first generation, RX100, is currently in the FDA pipeline and it is hoped it will be approved within the next three years. The research was initially funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' (NIAID) radiation countermeasures programme.

While there is no nuclear war on, researchers believe the drug has potential to be used on cancer patients to prevent side effects from radiation therapy: "For example in breast cancer patients, damage to the skin of the legion that is being irrigated is a problem. With prostate cancer – if you have radiation therapy in the rectum – it gets damaged."

They are now working to find out how to deliver the drug in a localised fashion that does not protect the cancer cells.

In addition, Tigyi said the drugs would make nuclear technology more acceptable: "I'd like to say it's an issue for mankind because we would benefit a great deal from peaceful uses of radiation technologies, but we are afraid of using it for two reasons – one is the complexity and engineering that goes into these power plants and the other is that we are defenceless.

"I think that having something that protects humankind that would make these technologies more acceptable to the people."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.