Parasitic roundworm infections can increase fertility in women in the Amazon

Parasitic roundworms can increase fertility in women in the Amazon, scientists have discovered. The "unexpected" finding showed that roundworm infection led to earlier first births and shorter intervals between children.

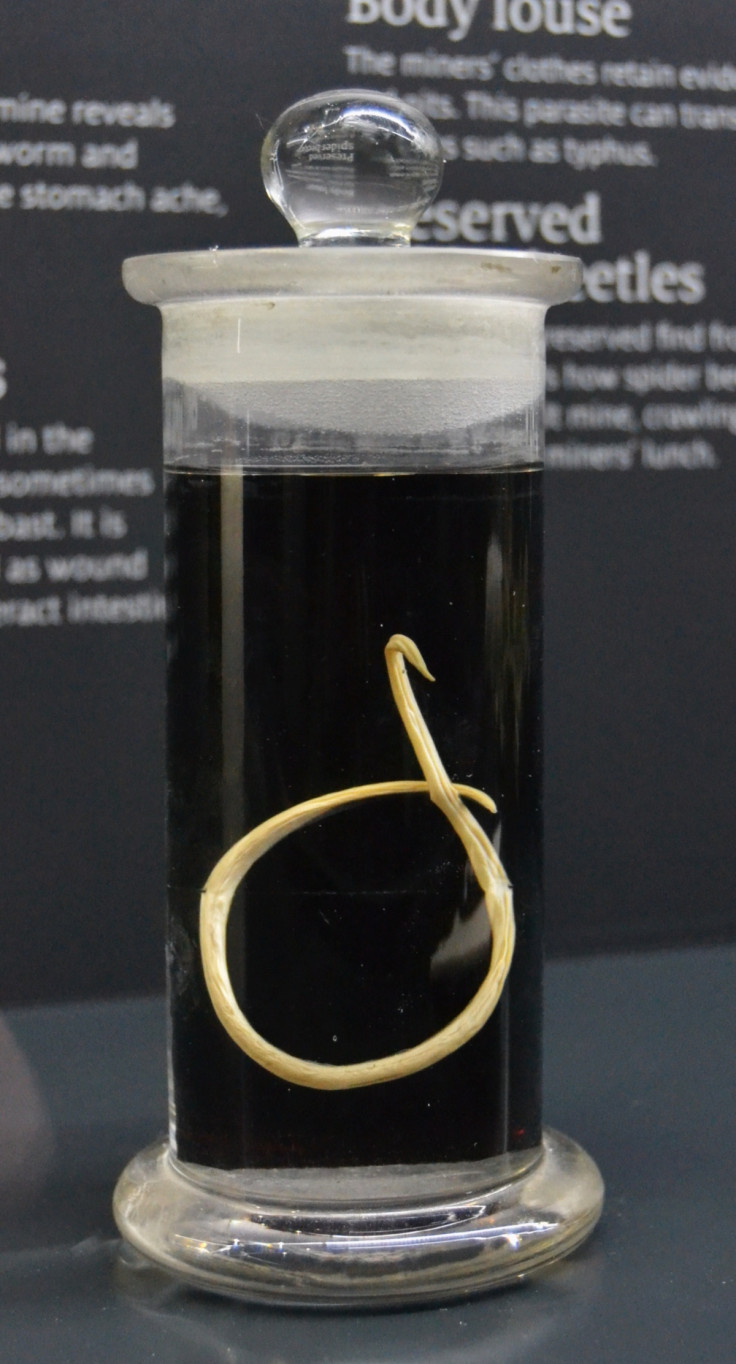

Research led by the University of California Santa Barbara showed that while roundworm infection could up fertility, hookworm infections can decrease it. The findings, published in the journal Science, showed that women who were repeatedly infected with roundworm had up to two more children than those who had no parasitic infections. In comparison, women who had repeated hookworm infections had three fewer children than women with no infections.

The team used nine years' worth of data from 986 Tsimane women living in the lowlands of Bolivia. They looked at natural fertility among the women, with 70% having parasitic infection. On average, the birth rate was nine children per woman.

Both parasites are known to result in different immune changes and reflect those that take place during pregnancy. During a normal menstrual cycles, level of Th2 T-cells increase. If conception takes place, Th2 levels increase throughout pregnancy and help to supress foetus rejection – an important factor in a successful pregnancy is that the maternal immune system does not reject the foetus. Th2 also helps to supress another type of T-Cell – Th1 – which appears to be associated with rejection.

Roundworms increase Th2 levels, while hookworms have been found to have a mixed Th1/Th2 response. Researchers believe these parasitic infections are indirectly affecting reproduction by changing the balance of these immune cells.

"Although consistent with our hypothesis, it is still unexpected to see positive associations between fecundity and A. lumbricoides [giant roundworm] infection, given that most parasites decrease reproduction," they wrote.

The team said, however, that this association might be the result of the suppression of responses that would normally decrease fertility – namely because it modulates an inflammatory response, it may limit reproductive suppression. Another idea is that the increased fertility is to do with fertility compensation, where reproduction is shifted to an earlier age in order to compensate for the increasing risk of mortality.

"Regardless of mechanism, these results indicate that across populations, helminths may have unappreciated effects on demographic patterns, particularly given their high global prevalence," they added.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.