Prehistoric Diet: Jurassic Dinosaurs Were Fussy Eaters

Dinosaurs from the Late Jurassic period were fussier eaters than their ancestors which led to a more peaceful co-existence, according to a study by the University of Bristol.

Research was carried out into a community of different species of sauropods, such as Diplodocus and Camarasaurus, from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation, an area of sedimentary rock in the western US, where over 10 species are known to have lived.

The prehistoric lands were dominated by sauropods between 210 and 65 million years ago. They were the biggest land animals at the time, weighing in at around 80 tonnes.

The size of these animals would mean that vast amounts of food would need to be consumed on a daily basis and it was a mystery how multiple types of sauropods were able to live alongside each other and still have enough food to go around.

This is especially because the harsh, semi-arid environment of the Morrison Formation would have made it difficult for plants to grow.

Another question raised was how such big dinosaurs were able to ingest enough food into their bodies to sustain themselves, with such small heads.

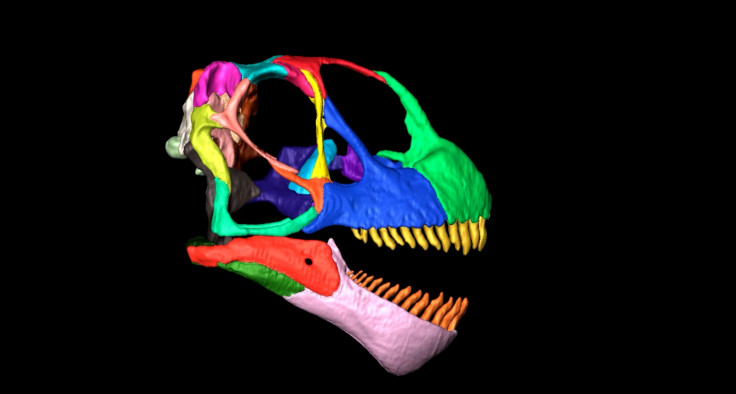

The scientists digitally reconstructed the skulls of a Camarasaurus and a Diplodocus through CT scans, along with the jaw and neck muscles of both species.

A computer model of a Camarasaurus skull was created using Finite Element Analysis (FEA), an engineering technique used to uncover stress and strain distribution.

The model was then compared to an existing model of a Diplodocus skull and biomechanical measurements from other sauropod species.

Scientists found that the differences in the animals' skulls and muscles meant that they were built to eat different types of vegetation.

"Our results show that although neither could chew, the skulls of both dinosaurs were sophisticated cropping tools," said David Button, a PhD student. "Camarasaurus had a robust skull and strong bite, which would have allowed it to feed on tough leaves and branches. Meanwhile, the weaker bite and more delicate skull of Diplodocus would have restricted it to softer foods like ferns."

The research has given scientists a better understanding of the evolution of sauropod feeding mechanisms and how they were able to eat enough food to sustain themselves.

"Our study provides insight not only into the ecology of dinosaurs but more generally into the mechanisms supporting species-richness in other animal communities, both from the fossil record and in the present-day," said co-author, Paul Barrett.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.