Scientists uncover the powerful role of scent in animal attraction

Study shows how smell is fundamental to forming a bond with others.

New research from the University of California has unravelled how animals form powerful attachment bonds with places or other animals early in their lives and the significant role that scent plays in this process.

These attachments, known as 'imprinting', have long been known to scientists. It explains how a baby lamb is able to locate its mother in a flock of identical animals; how salmon can migrate back to the exact spawning grounds where they were born after years at sea; and how ducklings know to follow their mother, despite just learning to walk.

However, researchers have been unable to explain the exact mechanisms of how this works until now. The findings, published in the journal Neuron, could have major implications for our understanding of social attraction and aversion in animals.

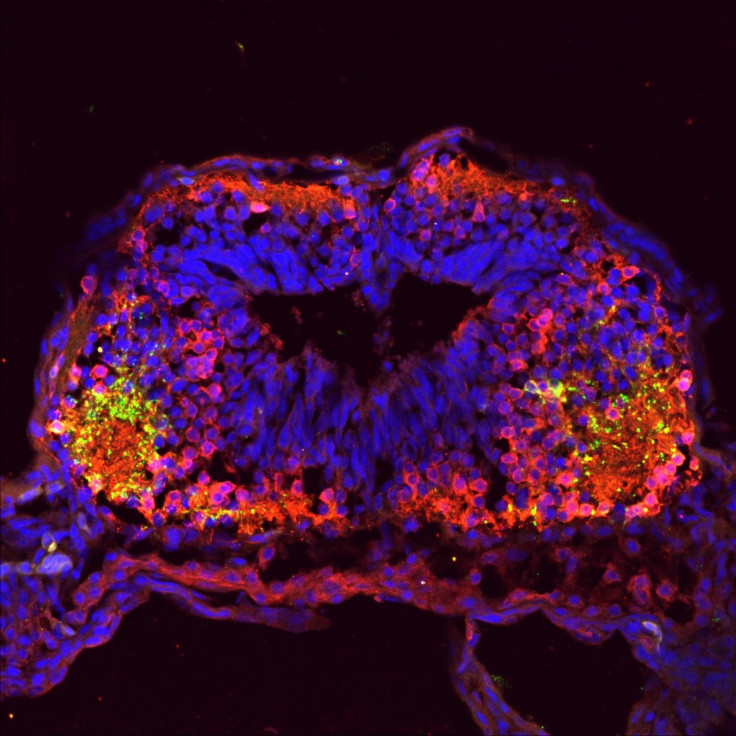

The neurobiological study examined tadpoles - which are known to swim in clusters – over eight years and focussed on scents produced by the frog family. The team identified the mechanisms by which very young tadpole chose to swim with their family members over non-family members. They found that those tadpoles that were exposed to scents from outside their family from very early on also tended to swim with the group that generated that smell, even if there was no relation.

The researchers discovered that this phenomenon was based on a process called "neurotransmitter switching" in which different neurotransmitters are activated in the animal's brain depending on whether the scent is coming from a related or unrelated animal. This strengthens the argument that smell and odour have a significant part to play in human interaction.

"You can imagine how important this is for social preference and behaviour. We have innate responses in relationships, falling in love and deciding whether we like someone. We use a variety of cues and these odorants can be part of the social preference equation", explained Davide Dulcis, an author of the study.

"Social interaction, whether it's with people in the workplace or with family and friends, has many determinants," noted Nick Spitzer, another author. "As human beings we are complicated and we have multiple mechanisms to achieve social bonding, but it seems likely that this mechanism for switching social preference in response to olfactory stimuli contributes to some extent."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.