Sepp Blatter reign over Fifa's multibillion pound football monopoly to continue despite arrests

Fifa's power relies on three things: the popularity of the game among millions of fans, the support of regional football federations and the billions of dollars the sport is awash with.

The figures are staggering. In 2014, Fifa raked in $5.7bn (£3.7bn) of revenue, the majority of which came from selling TV and marketing rights to the 2014 World Cup, which turned out to be the most lucrative sporting event in history. The organisation's cash reserves alone stand at $1.5bn (£977.6m).

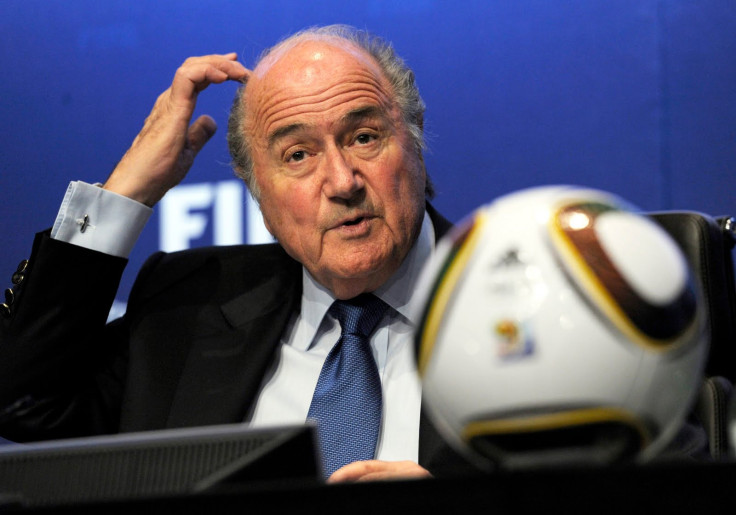

The man sitting atop this money mountain, Sepp Blatter, has been in power since 1998, serving four terms as its president. On 29 May, he will seek a fifth term amid yet another corruption controversy.

The US Justice Department and the Swiss government are probing Fifa officials on bribery charges and the legality of the bids for the 2018 and 2022 World Cups in Russia and Qatar respectively. Fifa's Zurich headquarters has also been raided.

But will this finally be enough to bring the money mountain crashing down and topple Blatter in the process?

What all the money is used for?

Despite the astronomical sums of money it makes, Switzerland-based Fifa pays no taxes because it is officially a non-profit organisation whose purpose is "to improve the game of football constantly and promote it globally, particularly through youth and development programmes". It must therefore spend all of its income on these things.

In theory, and with the correct corporate governance structures in place, this doesn't seem like such a bad thing. However, it gets murky when Blatter allegedly effectively uses Fifa's cash to buy support and keep himself in power. He does this by redistributing funds in the form of "development grants" to national football associations. They in turn vote for him, keep him in power and allegedly take a cut of the "grant".

The most recent example of this came only in April when it is said that Blatter caught wind of rebellion in the Caribbean and was worried he could no longer rely on the votes of the region's 25 nations in the 29 May election. A special trip to the Bahamas was then made where he promised up to $180m (£117m) in development grants over the next four years. Thus the merry-go-round continues.

More money, no problems

Even after development grants have been dished out, there is still a significant cash pile left. Outgoings for 2014 alone included $261m (£170m) in World Cup bonuses to member federations, $27m (£17.6m) splurged on a four-star hotel in Zurich and $39.7m (£25.8m) in executive committee wages and bonuses.

One of the most perverse aspects of the forthcoming election will be the fact that each of the 209 national football associations casts a single vote for the presidency. This means smaller countries, such as the Cayman Islands, have the same clout as more established footballing ones.

It has been argued the votes of some smaller nations, without a footballing tradition or infrastructure, can be "bought" with the promise of development grants.

The other B word

Alongside the prestige of hosting a World Cup, unscrupulous football associations and confederations are naturally keen to take a cut of the associated gravy train of merchandising, broadcast and match day income.

How keen? The latest arrests in New York relate to bribes allegedly given for football tournaments held in South America in the 1990s.

The Swiss investigation, meanwhile, involves proceedings "against persons unknown on suspicion of criminal mismanagement and of money laundering in connection with the allocation of the 2018 and 2022 football World Cups", according to the country's attorney-general.

A quick run down of some of the names: Jeffrey Webb, head of the confederation for North and Central America and the Caribbean (Concacaf), Jack Warner, former Fifa vice-president and Eugenio Figueredo, president of South American football governing body Conmebol.

It is not surprising. In 2010, two Fifa executive committee members were suspended for offering to sell their World Cup bid votes to undercover reporters, after which a whistleblower alleged Fifa members had offered to sell their votes for $1.5m (£977,746). Votes are seemingly available on the open market to the highest bidder.

Alongside allegations of bribery, Blatter himself has been accused of nepotism after awarding marketing rights for 2018 and 2022 to a company headed by his own nephew, Philippe.

What now?

Despite the arrests and investigations, the 29 May election is still scheduled go ahead. Blatter's only rival, Prince Ali Bin al-Hussein of Jordan, is unlikely to pose a serious threat precisely because of the money that could be at stake.

Corrupt football associations, confederations and their executives are unlikely to bite the hand that feeds them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.