'Super-fungus' carrying spider venom and scorpion toxins can kill malaria-carrying mosquitoes

The genetically engineered fungus can kill a mosquito with a single spore.

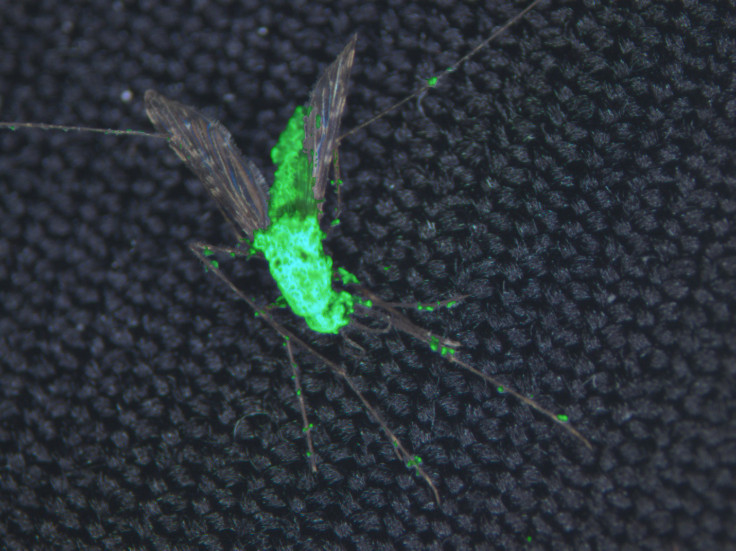

A genetically engineered fungus, designed to produce different potent toxins derived from spiders and scorpions, can infect and kill the mosquitoes that transmit malaria.

Malaria has proven to be an incredibly difficult disease to eradicate. There are several promising leads for a malaria vaccine, and trials are ongoing. Other efforts to halt the disease include releasing genetically modified mosquitoes.

Researchers have also been studying the fungus Metarhizium pingshaensei, which can kill mosquitoes. Its spores land on the insect's body and then penetrate the exoskeleton. The fungus grows inside the mosquito's body and eventually kills it.

But in the fungus' ordinary state it's not deadly enough to make enough of a dent in the mosquito population to stop them spreading malaria. A mosquito has to get a huge dose of the ordinary fungal spores in order to die.

In a study published in the journal Scientific Reports, scientists have now made the spores much more lethal, by introducing genes from scorpions and venomous spiders. Mosquitoes that were infected with 6 spores were completely unable to transmit malaria within 5 days, because it also reduced their ability to feed on blood.

"Our most potent fungal strains, engineered to express multiple toxins, are able to kill mosquitoes with a single spore," said study author Brian Lovett of the University of Maryland.

"We also report that our transgenic fungi stop mosquitoes from blood-feeding. Together, this means that our fungal strains are capable of preventing transmission of disease by more than 90% of mosquitoes after just five days."

Mosquitoes don't just transmit malaria, they also spread dengue fever, yellow fever, viral encephalitis and filariasis. Tackling them with a super-fungus could potentially reduce the risk of all these diseases, said Raymond St. Leger, also of the University of Maryland and a study author.

"The toxins we're using are potent, but totally specific to insects," he said. "They are only expressed by the fungus when in an insect," said Raymond St. Leger, another author of the study.

The toxins are not thought to affect insects such as bees, which do not transmit human diseases and are suffering population decline globally. The team's next steps are to test whether the super-fungus is safe against a range of common insects, such as gnats and midges, to ensure it only targets mosquitoes.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.