Technique to Detect Distant Earth-Like Planets Will Be Tested on Venus First

A Harvard-Smithsonian team hopes to identify Earth-like planets by calibrating the spectrograph to read very small Doppler shifts caused by the tug of these planets on their stars.

They plan to test this by rediscovering Venus through the planet's tug on the Sun.

So far astronomers have identified more than 1,700 exoplanets (planets outside our solar system).

Most of these were discovered by the traditional transit method, which measures the decrease in brightness when a planet moves in front of its star. This method only provides information about the planet's size, but not its mass.

The other method used is to measure the Doppler shift in frequency of light when an object moves relative to the earth. By watching this over a period of time, astronomers can assess the mass of the planet tugging at its parent star.

But this method works only for detecting massive planets as spectrographs cannot detect shifts below 1 metre per second.

Using 8000 lines of laser light to combine with starlight of the same wavelength, the duo Chih-Hao Li and David Phillips will be able to map the spectrograph down to 1/1000 of a pixel improving its performance.

They plan to use their 'green astro-comb' to detect small planets light years away but before that they will turn the spotlight on our sun to detect the tug of Venus and measure the Doppler shift.

Since the size and mass and period of revolution of Venus are already known, they will be able to check the efficiency of their comb in picking out distant Earth-like planets.

The Harvard-Smithsonian team is installing their device on the High-Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher-North (HARPS-N), a new spectrograph designed to search for exoplanets using the Italian National Telescope.

"We will look at the thousands of potential exoplanets identified by the Kepler satellite telescope by the transit method. Together, our two methods can tell us a lot about those worlds," Li said.

The duo will present their paper at a conference of The Optical Society.

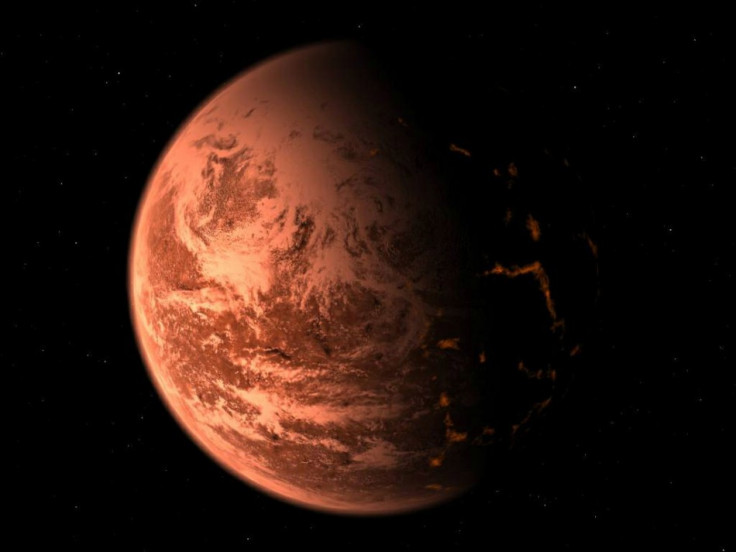

The method is precise enough to help astronomers identify Earth-like planets in the habitable 'Goldilocks zone,' the orbital distance where water exists as a liquid.

Recently, water was detected on a small planet 124 light years away.

While the discovery of four planets comparable to the size of earth and at the right distance from the star saw much excitement, finding out the chemical composition often becomes difficult with distance.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.