Uffington hill carving was worshipped as 'sun horse' in prehistoric Britain

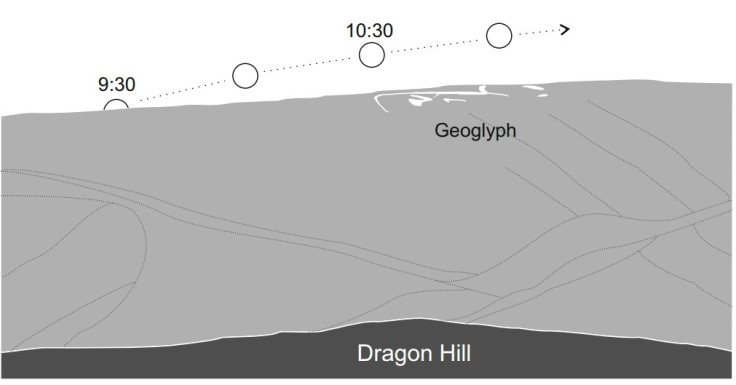

The location and orientation of the Uffington White Horse has been linked to the arc of the midwinter sun.

A huge prehistoric geoglyph depicting a galloping horse is traditionally thought to have been a symbol of ownership, territory or group identity for the prehistoric humans living on the Berkshire Downs. But now scholars are taking a second look at the 110-metre-long hillside carving. A new archaeological interpretation argues that it is a representation of a sun horse, a mythical beast that pulled the sun across the sky like a chariot.

The Uffington White Horse in the south of England is one of the oldest giant carved hill figures, or geoglyphs, in the world. The elongated, stylised horse is best visible from the sky, but was built millennia before a human would see it from that vantage point. It is thought to have been carved into the hillside, exposing the white chalk bedrock, in the late Second Millennium BCE or the early First Millennium BCE.

Archaeologist Joshua Pollard of the University of Southampton visited the site many times before it struck him that the traditional interpretation didn't quite fit. As a mark of ownership intended to be seen for miles around, it is positioned rather awkwardly. It sits on the gentler slope of a valley. It could just have easily have been carved into the steeper side of the valley, which would have made it much more easily to make out from the ground.

The horse's body does not lie parallel with the contours of the hill, but it instead it is turned to point slightly uphill, as though it is bounding up the slope. Ahead of it, several other prehistoric archaeological sites lie in its path, including a long mound, a round barrow and Uffington Castle, which was built in the Iron Age. Behind the horse is a site known as Dragon Hill. The view from this site makes it appear to bound up the hill towards the west.

Why was the horse carved into the gentler slope, making it more difficult to see from the ground? And why is it angled uphill? And why is the horse running, rather than standing still?

All of these questions are answered if the horse is seen not as a territorial mark, but as a sun horse.

"If you follow the horse's position and its track of movement, then that corresponds with the arc of the midwinter sun," Pollard told IBTimes UK.

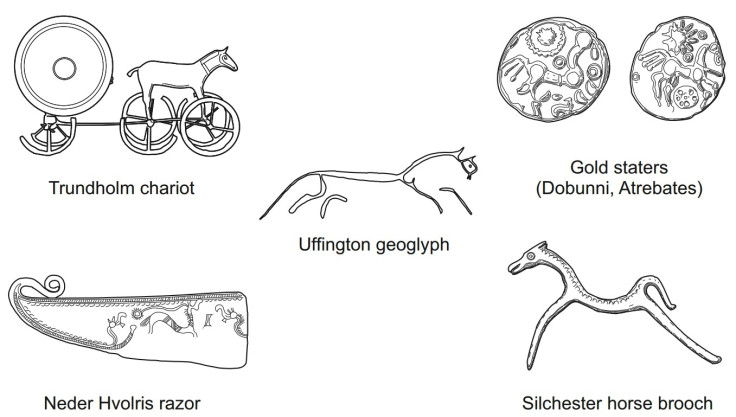

The sun horse was a widespread concept in Bronze Age Europe. Similar images can be found engraved on artefacts from bronze razors to gold and silver coins from the period. The tradition has much older roots in Indo-European cultures.

"The notion of the sun as divine, pulled across the sky by a horse or horse-drawn chariot during the day, and transported through the underworld at night by boat or chariot, is a recurrent feature of Indo-European mythologies and cosmologies," Pollard writes in a paper on the White Horse in the journal Antiquity.

This is the reason for the horse's otherwise counterintuitive position, Pollard says. It is a sun horse in motion, galloping along the line of the midwinter sun. The interpretation, if correct, offers a connection in cultural traditions between Britain and the rest of Europe at the time, and one stretching far back into prehistory.

"We're not necessarily seeing a different kind of religious tradition in southern Britain compared with the rest of Europe," Pollard said. "What we're hinting at is that that this particular location on the Berkshire Downs was perceived as having enormous sacred significance."

"We can perhaps think about the landscape itself and the very dramatic natural features we find at Uffington as being a focus for various kinds of innovation and religious activity. It may have acted as a regional or even inter-regional focus for ceremonial activity."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.