150 years after the Confederacy seceded, does South Sudan have a better chance than Dixie?

Last December saw the 150<sup>th anniversary of South Carolina's decision to secede from the United States of America, a move that was quickly copied by a string of southern states and led to the creation of the short-lived Confederate States of America.

A century and a half later and thousands of miles to the east, the African country of Sudan looks set to follow the U.S.A. in its own way and split between north and south and once again it's the south which is looking to secede.

Yesterday saw the beginning of a week long referendum in South Sudan to determine whether or not the region should remain part of a united single country. It is widely expected however that the result, due next month, will see secession roundly endorsed by southern Sudanese.

Already the President of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, a charming man wanted by the International Criminal Court for genocide, has said that the potential new polity of South Sudan is not a viable state and will not be able to provide for its people.

No doubt the new country, if and when it is formed, will face difficulties but it will almost certainly outlive the Confederate States of America that lasted a mere four years before being re-absorbed into the Union.

South Sudan's is likely to last a good deal longer because, unlike the C.S.A. it is seceding after its civil war and not before. The vote on secession was agreed six years ago in a 2005 peace treaty that brought a close to a war which spanned three decades and killed nearly two million people.

Despite decades of war the central government in northern Sudan could never cow the South into submission, despite the terrible suffering and destruction inflicted in the course of the conflict. Both sides, it seems, are tired of war, to the extent that even Mr Bashir has said he will allow the South to secede.

By contrast when the southern states of America attempted to secede, they were trying to do so from a Union which had just elected a fresh, energetic and strongly unionist president in the form of Abraham Lincoln, rather than from a tired old alleged war criminal.

The Confederacy might have lasted a good deal longer if it had attempted simply to defend its own borders, rather than indulging romantic and fanciful notions that a largely rural society could defeat an industrialised one with twice its population. Such a strategy would no doubt have claimed more lives on both sides than was already the case but would almost certainly have prolonged and perhaps even saved the C.S.A's short existence.

Having already fought their civil war the people of South Sudan look likely to be able to enjoy their independence should they vote for it, but they may still face pressure from the North that may undermine it.

President Bashir has already said that should the South secede its citizens will not be eligible for dual citizenship in the north. He has also warned that the war may be resumed if the South attempts to seize the oil rich Abyei region (which will hold a separate vote on whether to join the North or South) by force.

Despite this South Sudan will not be at the economic mercy of the North to the extent that the Confederacy was to the Union.

The Confederacy's main source of wealth was of course from its exports of cotton. But with the Union holding naval superiority the C.S.A found no major outlet for its exports, being boxed in by Union territory to the north and a Union naval blockade on the south and east. Such was the intensity of the blockade that some in the North believed the Confederacy would collapse without pursuing a long and destructive land war.

The south of Sudan by contrast will be bordered by five other African nations and will hold 75 per cent of Sudan's oil reserves, the revenue from which will be shared 50-50 with the North as part of the 2005 peace deal, thus minimising incentives for the North to sabotage the South's prospects.

Recognition for the new African nation is also unlikely to be a problem. The Confederacy was desperate to be recognised as a new state by even one of the major European powers, yet despite sympathies with the South and its cause none loved it so much that they wanted to risk aggravating the considerable power of the United States. It is unlikely that Mr Bashir commands so much fear and respect in the international community as did Mr Lincoln.

Finally South Sudan faces the best chance of beginning the long process of building itself as a nation if it can remain united internally, something that the Confederacy, with its emphasis on "states rights" failed to do as each state attempted to defend itself while neglecting the whole polity.

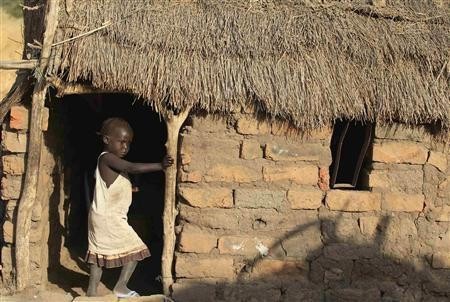

In all South Sudan, pitiful and ruined as it is after years of bloody war, still has a long road ahead of it before it becomes anything resembling a prosperous nation-state. But it can take comfort from the fact that, unlike the Confederacy, its decision to secede comes after rather than before the desolation of war and that from here on the only way can be up.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.