After Isis: Schools reopen and normality starts to return to eastern Mosul

Taking the west side could prove much tougher; the jihadists are expected to put up a fierce fight as they are cornered in a shrinking area.

Now that Iraqi forces have recaptured eastern Mosul, they are preparing to push into the western part of the largest city held by Islamic State (Isis). It took 100,000 Iraqi troops, members of regional Kurdish security forces and Shia paramilitaries, backed by air and ground support from a US-led coalition, almost 100 days to retake eastern Mosul.

Taking the west side could prove even tougher as it is criss-crossed by streets too narrow for armoured vehicles. The jihadists are expected to put up a fierce fight as they are cornered in a shrinking area, but the narrow streets could also deprive them of one of their most effective weapons: suicide car bombs.

If they lose Mosul, the self-described caliphate that once straddled parts of Iraq and Syria is widely expected to collapse. But the militants are likely to wage an insurgency in Iraq and inspire attacks in the West.

Many Iraqis worry that destructive forces such as sectarianism, which already provoked one civil war since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, would destabilise Iraq even if IS is completely removed from Mosul. The hardline jihadists were welcomed by some fellow Sunni Muslims when they seized Mosul in 2014 because the community, a majority in the city but a minority in Iraq, felt marginalised by the Shia-led government in Baghdad.

Those bitter feelings have not faded, adding to the sense of uncertainty in a city with rows of buildings pulverised by airstrikes and desperate for water and electricity supplies.

The city is coming back to life, with markets and shops reopening and people selling once-prohibited goods such as cigarettes openly on the streets. Yet the damage of battle is everywhere – and fighting rages just a few miles away.

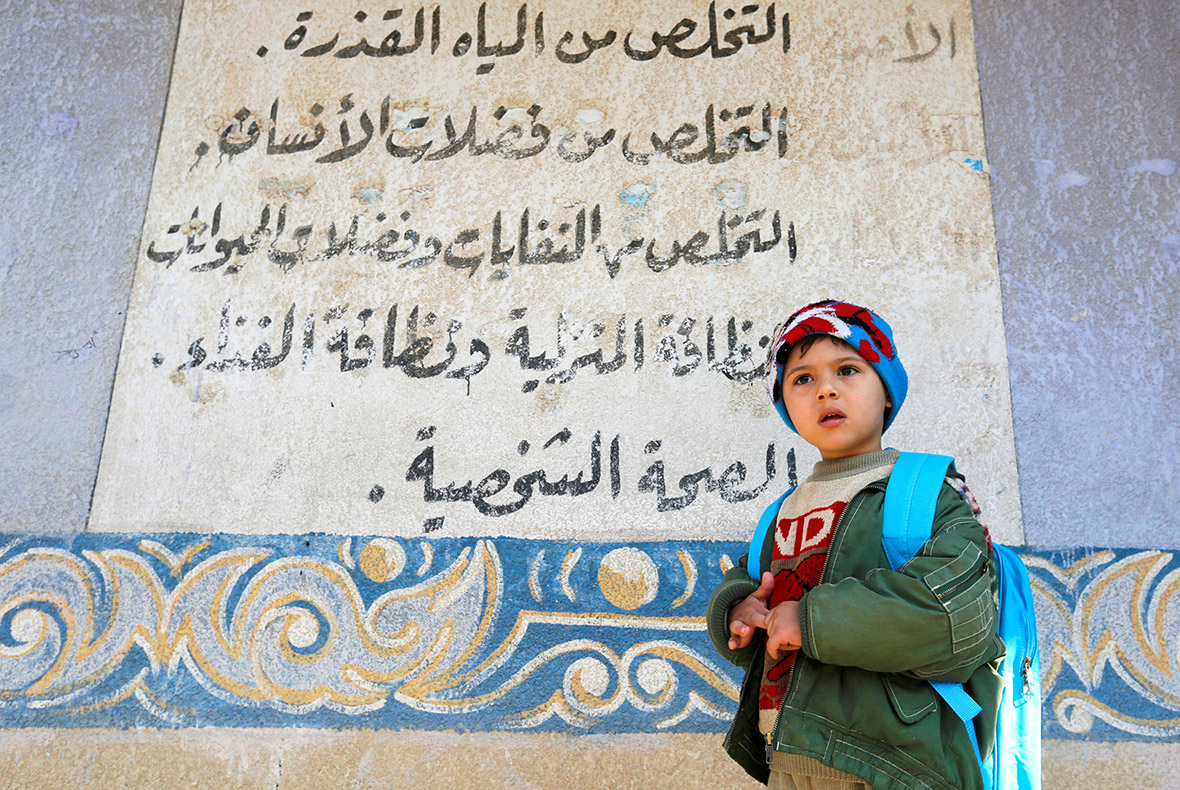

Schools in the east of the Iraqi city of Mosul are seeking to return to a semblance of normality after two years under IS rule when they were either shuttered or forced to teach a martial curriculum that included lessons in bomb making. Around 40,000 students – most of whom have been kept at home by their parents since the militants captured Mosul in 2014 – will attend around 70 schools in the coming weeks after the buildings have been checked for unexploded bombs.

A return to normality will not be easy for children, who bear the scars of living in the IS's de facto capital in Iraq and the bitter battle for the city. They could face psychological hurdles, as might their teachers, many of who told Reuters they had been threatened with being hung from their schools' walls if they did not continue teaching under IS. One schoolyard in the area has been turned into a cemetery covered with dozens of freshly dug graves.

A nearby house once served as a holding area for women, possibly some of the numerous people that IS forced into sex slavery. Baby strollers and clothes were abandoned in a room. Next door was a makeshift prison and torture centre.

Iraqi forces estimated the number of militants inside Mosul at 5,000-6,000 at the start of the battle, and have said 3,300 have been killed in the fighting.

Some 750,000 people live in western Mosul, according to the United Nations. More than 160,000 civilians have been displaced since the start of the offensive in Mosul, which had a pre-war population of around two million, UN officials say. Aid agencies estimate the dead and wounded – both civilian and military – at several thousand.

The UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Iraq, Lise Grande, expressed concern for civilians in the western half of Mosul in a statement signed by 20 international and local aid groups. She said the cost of food and basic goods is soaring, water and electricity are intermittent and that some residents are forced to burn furniture to keep warm.

"We hope that everything is done to protect the hundreds of thousands of people who are across the river in the west," Grande said in the statement. "We know that they are at extreme risk and we fear for their lives."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.