Battle of the Somme centenary: Soldiers' letters and photos reveal horrors of First World War

New book by historian Richard van Emden offers vivid impression of what it was like to serve in the Somme.

On Friday (1 July 2016), the world marks the 100th anniversary of the first battle of the Somme – one of the bloodiest battles in history. By the time it ended on 19 November 1916, British, French and German casualties totalled more than 1,250,000.

The first day of July 1916 was the heaviest single day in terms of British casualties in the whole war, with 21,392 killed and 35,493 wounded.

The British attacked with 15 divisions on a front 15 miles north of the Somme, and the French with five divisions on an eight-mile front, mainly south of the river. The absence of the element of surprise, combined with strong German resistance, turned most of the British attack into a failure.

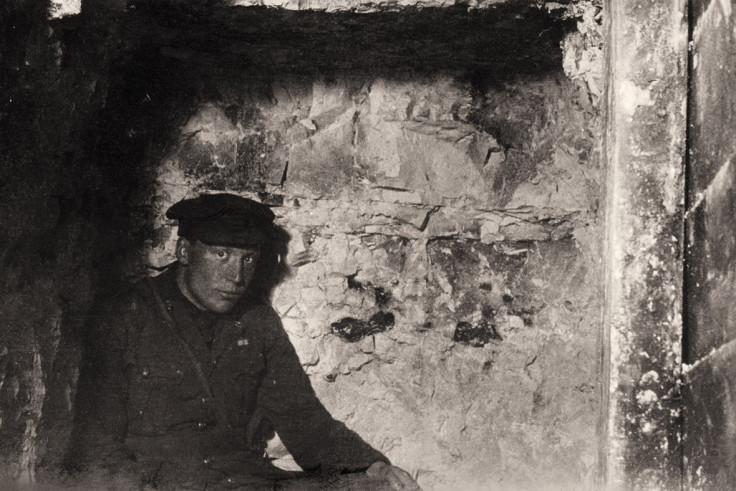

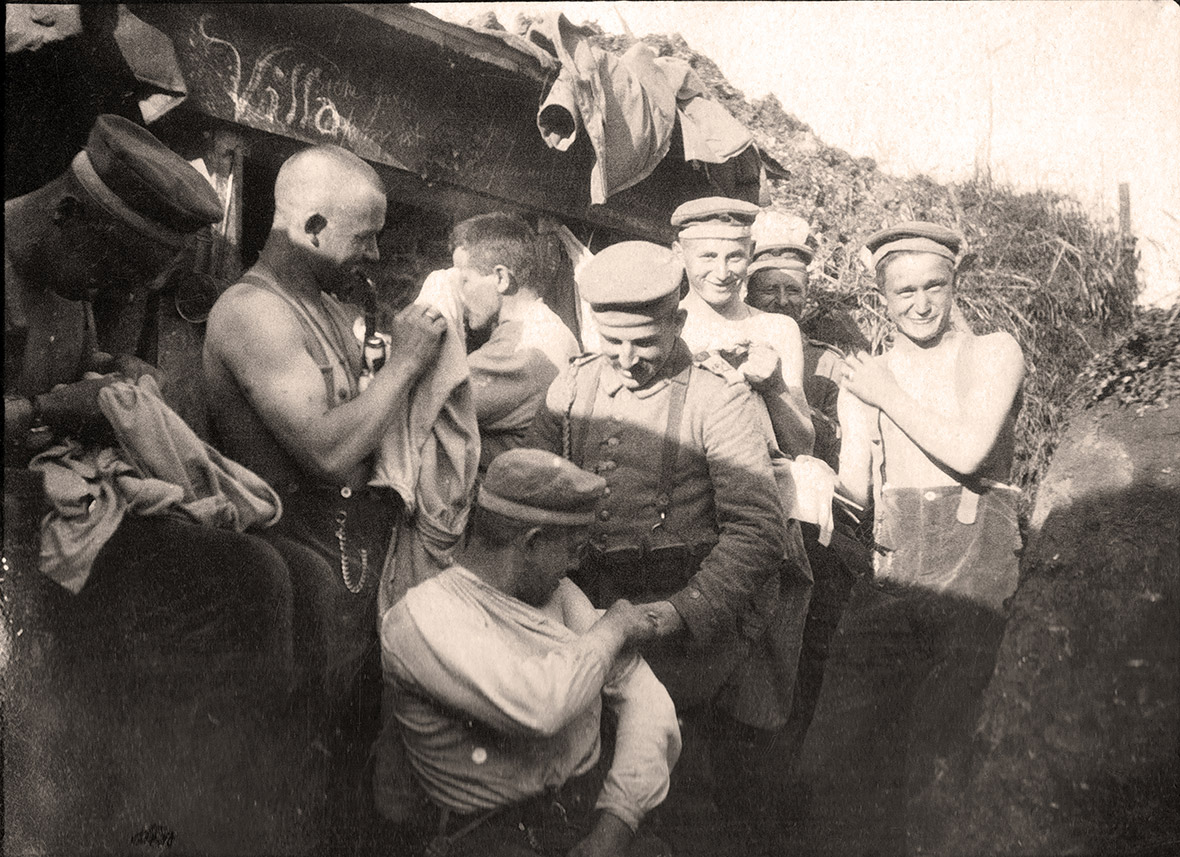

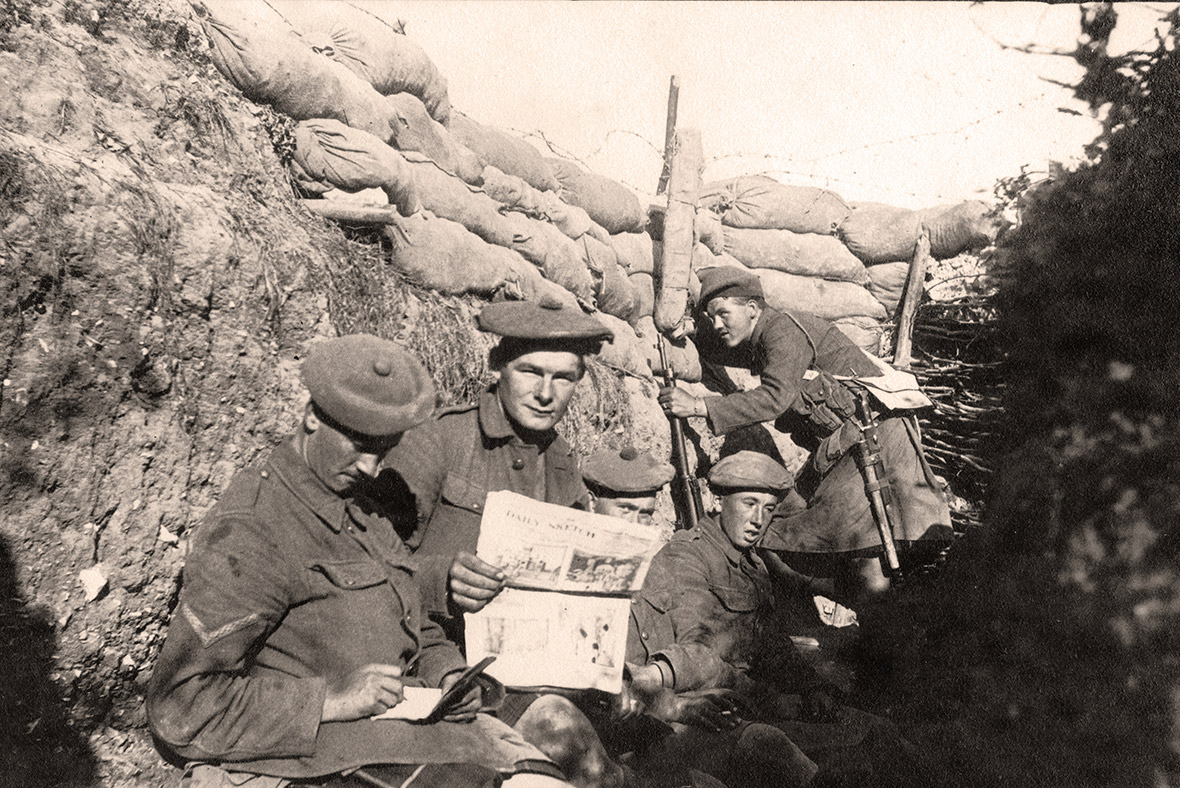

A new book offers a vivid impression of what it was like to serve on the Somme. Historian and First World War expert Richard van Emden tells the story of the Somme through the soldiers' own words – written in diaries, letters and memoirs – and photographs that the men themselves took on their own illegal cameras. The army banned cameras just before Christmas 1914 when it was discovered that soldiers – mainly officers – were selling their photographs to the British press.

In his introduction to The Somme: The Epic Battle in the Soldiers' Own Words and Photographs, Van Emden writes: "Men stopped taking pictures not simply for fear of army retribution, but because they were increasingly tired of the war. They had lost that sense of adventure and excitement that had encouraged so many to take their cameras in the first place." Fortunately, for posterity, cameras were still kept by a small number of men.

As winter 1915 approached, heavy rain turned the British trenches into hellish mudbaths. Second Lieutenant Frederick Roe, 1/6th Gloucestershire Regiment, wrote: "The German choice [of the high ground] naturally ensured that all the surface waters in rainy weather and throughout the winter drained downhill into our trenches because there was nowhere else for it to go."

In a letter home, Private Sydney Fuller, 8th Suffolk Regiment, wrote: "After these weeks of rain alternating with hard frosts, the state of what is left of the trenches is indescribable. Where our dugout emerges from below on to the trench bottom we have a dam either side. One side is 21⁄2 feet of water and another of mud, now all frozen, but not hard enough to bear; and the other is about a foot deep."

On 24 June, the British began their bombardment of enemy trenches. The day of the assault had been set for Thursday 29 June, but bad weather caused a 48-hour postponement, leaving the batteries and trench mortars to continue until the morning of 1 July.

Private Frank Williams, 88th Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps, wrote: "Very wet. Orders at last. Moved off 9.30pm, as we neared the line met huge columns of infantry marching up. Nearing Mesnil a horseman rode up and warned us to put on our goggles, which I did quickly. For my eyes had already started to run and a strong smell as of mustard and cress filled the air [tear gas]. The tears were running down my face so that I could hardly see at all and we practically felt our way along to Mesnil, where after a great deal of delay we got into dugouts, good deep ones I'm thankful to say, my ears splitting almost from the continuous burst of shells and roar of our artillery."

On 30 June, Second Lieutenant John Engall, 1/16th London Regiment, wrote: "My dearest Mother and Dad, I'm writing this letter the day before the most important moment in my life – a moment which I must admit I have never prayed for, like thousands of others have, but nevertheless a moment which, now it has come, I would not back out of for all the money in the world. The day has almost dawned when I shall really do my little bit in the cause of civilisation. Tomorrow morning I shall take my men – men whom I have got to love, and who, I think, have got to love me – over the top to do our bit in the first attack in which the London Territorials have taken part as a whole unit."

On 1 July, the British guns opened up a final hurricane bombardment on the enemy trenches, and a number of mines were detonated under the German lines. And then the infantry assault began. Private Frank Lindley, 14th York and Lancaster Regiment [2nd Barnsley Pals] wrote: "The birds were singing in the copses around. It was a beautiful day, beautiful. We had this morning chorus and then it all happened, just like a flash. We were stood there waiting, ready for the officer to blow his whistle, and our barrage lifted and then bang! A great big mine went up on the right-hand side. We saw it going sky-high, one huge mass of soil. It shouldn't have gone up till we were on the top because it alerted the Germans and they were up waiting for us and when we attacked they cut us to ribbons, totally ripped us to pieces ... Bullets were like a swarm of bees round you, you could almost feel them plucking at your clothes."

The 36th Ulster Division were in Thiepval Wood, the trees helping to conceal their presence. They made a dash across no-man's-land to a sunken lane. Lieutenant Colonel Frank Crozier, 9th Battalion Royal Irish Rifles, wrote: "This spirited dash across no-man's-land has cost us some fifty dead and seventy wounded. The dead no longer count. War has no use for dead men. With luck they will be buried later; the wounded try to crawl back to our lines. Some are hit again in doing so, but the majority lie out all day, sun-baked, parched, uncared for, often delirious and at any rate in great pain.

"All at once there is a shout, Lt Crozier continued. "Someone seizes a Lewis gun. ' Thee Germans are on us' goes round like wildfire. I see an advancing crowd. Fire is opened at 600 yards' range. The enemy fall like grass before the scythe. I look through my glasses. 'Good heavens,' I shout, 'those men are prisoners surrendering, and some of our own wounded men are escorting them! Cease fire, cease fire, for God's sake,' I command. The fire ripples on for a time. The target is too good to lose. 'After all, they are only Germans,' I hear a youngster say."

Many battalions would lose more than three-quarters of their strength in the assault, but few would be as hard hit as the 8th King's OwnYorkshire Light Infantry. Attacking up a steep slope they were cut down, the wounded being picked off by snipers. The battalion suffered 539 casualties.

The regiment's Sergeant Walter Popple wrote: "As I neared the enemy wire, I felt a sharp thud accompanied by a pain in my chest and I fell. A German was firing from an advanced post, picking off anyone he saw, including the wounded. As I glanced upwards, he saw me. He fired, a bullet taking the heel off my boot. I came to the terrible decision that it was better to get it over with quickly and die, rather than be picked off piece by piece, so I raised my head and pushed myself upwards, almost kneeling to look straight down the muzzle of his rifle. A sharp crack, and my helmet flew off and my neck stiffened. I sank to the ground. Utter silence. At first there was a buzzing sensation in my head and then sharp piercing darts of pain. Had I been killed as I first thought? I dared not lift my head and there I remained through the heat of the day, wondering if in fact part of my head had been blown away."

"You could hear the bullets whistling past and our lads were going down, flop, flop, flop in their waves, just as though they'd all gone to sleep,' wrote Private Frank Lindley, of the 14th York and Lancaster Regiment. "Second Lieutenant Hirst was near to me, almost touching. He had just got wed before we came away, and was a grand chap, but it wasn't long before he got his head knocked off."

In this gallery, IBTimes UK presents just a few of the photos published in the book. To see more, many of them previously unseen, and to read more of the soldiers' vivid accounts of the horrors of war, get The Somme: The Epic Battle in the Soldiers' Own Words and Photographs by Richard van Emden, published by Pen & Sword Books, recommended retail price £25 (also available in paperback for £14.99).

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.