Bring super-rich migrants to UK out of the shadows

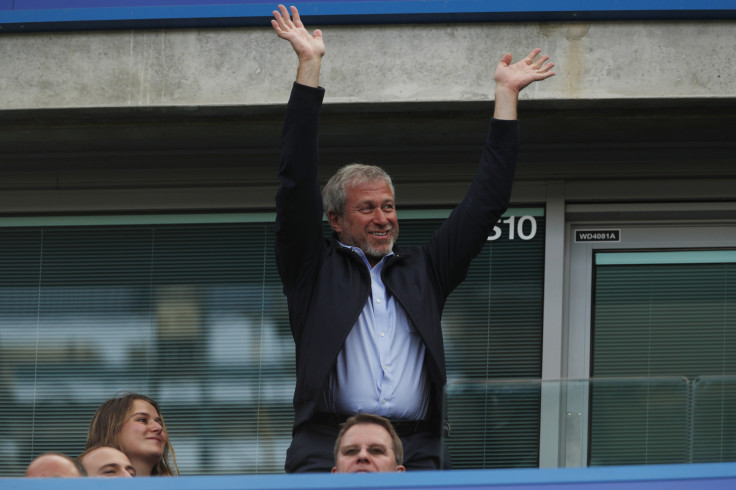

Chelsea FC owner Roman Abramovich's latest visa woes highlight the need for a code of ethics to make investment migration more transparent.

If, as many say, Brexit represents a risk to Britain trade and access to the customs union, then no-one has told the world's wealthy, who have never been so keen to come to this country and capitalise on its financial infrastructure.

In the third quarter of last year the Home Office issued 114 Tier 1 Investment Visas – a rise of 24 per cent over the previous quarter, and an astonishing increase of 247 per cent on the previous year. Simple maths will tell you that is just under a quarter of a billion pounds of investment into the UK economy, and that is before you consider visa extensions that cost up to £10 million. And then there is the investment made by individuals into the UK property market, the stock market, bonds or businesses. The list is endless.

Except the narrative around immigration rarely focuses on high-net worth individuals; when it does, it's seldomly positive. And there is sometimes a perception that people taking up the government's Tier 1 Visa are using their wealth to jump the immigration queue.

One of the topics at the very top of the media agenda currently is immigration, specifically the current situation concerning the Windrush generation. Yet just as the Windrush generation has made incredible contributions to this country – as have so many other of our citizens born overseas – this doesn't mean that others should be denied the same opportunity. Immigration should be fair to everyone who contributes to this country, and that means upholding the letter and the spirit of the law.

Before we go into this in more detail, let's be clear what the process actually entails. Investment migration enables anyone with £2 million to invest in the UK economy to be granted a Tier 1 Investment Visa. This money needs to be invested in a limited number of ways: in UK Government bonds, or share or loan capital in active, trading and UK-registered companies.

Naturally, this represents an important economic opportunity for the UK, especially at a time of such political and financial uncertainty. The money, which immigrants needs to invest within three months of landing in the UK, brings a major cash injection to the economy, helping to create jobs, sustain start-up businesses, and improve our productivity.

It's not just the UK that runs investment migration programmes. By the end of 2017 there were over 80 active programmes in most major world regions. Citizenship-by-investment is a $3bn global industry (residence-by-investment being worth considerably more), bringing major benefits to countries around the world. To take just one example, impoverished Greece has enjoyed a windfall of €1.5bn thanks to its own Golden Visa programme.

And we do these migrants a disservice if we only focus on their money. Along with their investment, they can bring a wealth of knowledge and contacts with their home countries that can be of enormous help to business and government.

Of course, having any unchecked investment migration programme is open to abuse, and without oversight and a rigid code of ethics it leaves itself open to claims of corruption, or the potential to circumvent global regulation standards, such as The Common Reporting Standard (CRS), in addition to others.

Where does one start with a code of ethics? We believe that such a document should cover such issues such as integrity and ethical practice, competence and objectivity, confidentiality, conflicts of interest and regulatory compliance – among other issues.

Who should be involved in drawing up this code? In our view, it's everyone's business – from government to business to academia, all should pitch in to give their viewpoint on how we can make investment migration both ethical and effective.

And once drafted, will these be adamantine rules – fixed for all time? It's hard to see how they can be. Investment migration is a relatively new idea, and as we grope towards a truly ethical way of managing this process across different countries and jurisdictions, we will have to accommodate new viewpoints and adapt to changing economic and political circumstances and realities.

In fact, we've have made a start on this issue with our Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct: the first stab at creating a worldwide framework for industry best practice. To create the code, we consulted with external academics and professional practice experts to give as well-rounded a view as possible – but we don't believe that this document puts an end to all debate on the ethics of investment migration.

Rather, we see it as the first draft of a living, evolving document – one that every stakeholder from business, government and academia needs to help extend and improve.

The ultimate goal is to ensure that investment migration brings value to countries of destination and investment, and that the price for residence or citizenship ends up not in the pockets of kleptocrats, but invested in a way that will bring value to ordinary citizens.

What's more, by being open about the rigorous processes that aspiring citizens must go through, we can avoid the opacity that sours so much of the discourse around investment migration. We can ensure, for example, that we remove speculation that Tier One visas are all part of grand political and diplomatic games – as the coverage of Roman Abramovich's recent visa troubles has so heavily insinuated.

Investment migration suffers from staying in the shadows, and that's bad news for the countries who stand to gain so much – including the UK. Every citizen, every business and public body is, in their own way, responsible for making immigration work for all.

Bruno L'ecuyer, Chief Executive, Investment Migration Council

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.