Climate Change: 'Unexpected Increase' in Ozone Destroying Substance HCI

There has been an unexpected increase in a substance linked with the destruction of the ozone layer, scientists have said.

Under the Montreal Protocol, the 1989 treaty to protect the ozone layer by phasing out destructive substances, it was expected there would be a steady decline in these chemicals.

However, researchers at the University of Leeds working with an international team of scientists have found there has been an increase in atmospheric hydrogen chloride (HCI).

Published in the journal Nature, experts said the recent and unexpected increase is due to a temporary anomaly in atmospheric circulation, which changes the balance between CFCs and their breakdown product – HCI.

The increase in HCI was only seen in the northern hemisphere. Concentrations of the substance declined in the southern hemisphere in line with expectations.

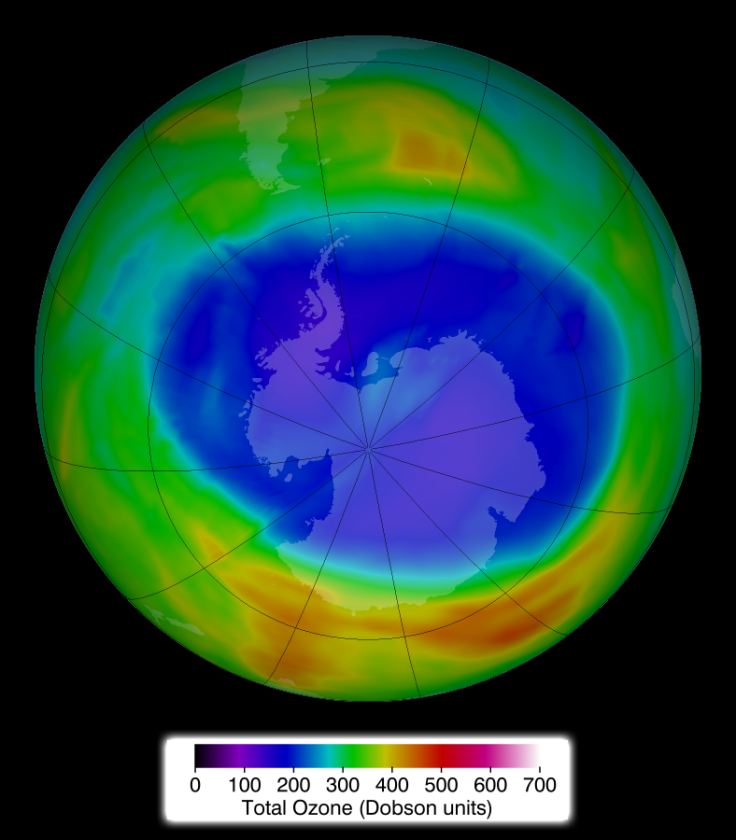

Nasa recently announced the ozone hole over the Antarctic was about the size of North America at its peak this year – a very small increase on the maximum reached last year.

Through comparison with detailed computer models, we have identified this decline as temporary due to changes in upper atmospheric wind patterns, so we remain optimistic that the ozone layer will recover during the second half of the century

Martyn Chipperfield, who led the modelling work for the study, said: "The expected deterioration of ozone-destroying chemicals in the atmosphere is certainly more complex than we had imagined.

"Rather than a steady decline, these findings have presented a rather more complicated picture.

"Through comparison with detailed computer models, we have identified this decline as temporary due to changes in upper atmospheric wind patterns, so we remain optimistic that the ozone layer will recover during the second half of the century."

He said there are natural differences between the northern and southern hemispheres, which explain the differences between the two regions in terms of HCI.

"While atmospheric chlorine levels remain high we may see cases of large ozone depletion, especially over the polar regions," Chipperfield said.

Researcher Peter Bernath, from the University of York, added: "Atmospheric variability and perhaps climate change can significantly modify the path towards full recovery and, ultimately, it will be a bumpy ride rather than a smooth evolution.

"The recovery of ozone-depleting chemicals in the atmosphere is a slow process and will take many decades. During this time the ozone layer remains vulnerable."

However, the team said their findings should not cause alarm.

Study leader Emmanuel Mahieu said: "It's important to say that the Montreal Protocol is still on track, and that this is a transient reversal in the decline of HCl, which can be explained through a change in atmospheric circulation, rather than rogue emissions of ozone-depleting substances."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.