Did humans turn the Sahara from a lush, green landscape into a desert?

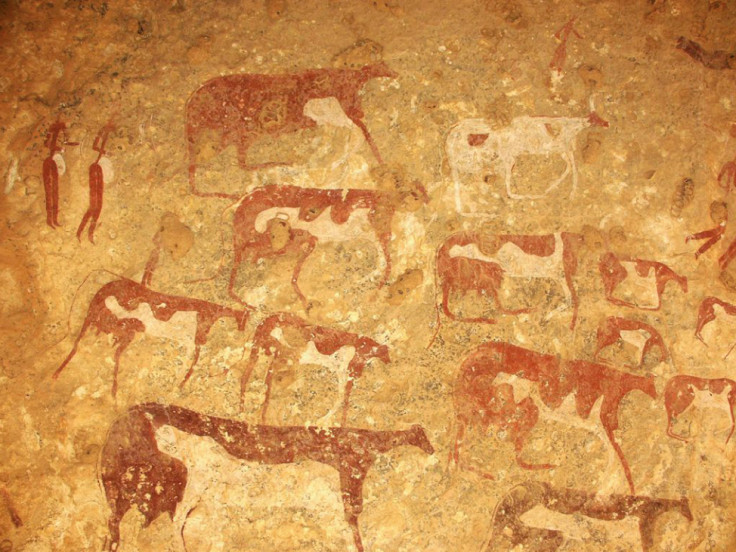

Cattle grazing on pastures that were on an ecological knife edge could have pushed the Sahara onto the path of desertification.

The Sahara used to be a fertile landscape with lush vegetation thousands of years ago, but something killed that landscape, leaving only desert behind. Neolithic humans may have played a role in pushing it over the edge of an ecological tipping point, an archaeological study finds.

The Sahara used to be a lush, green environment as little as 6,000 years ago, when humans grazed cattle on green pastures. Theories for what turned the Sahara into a desert in a period of just a few thousand years include shifting circulation in the tropical atmosphere and changes in the Earth's tilt.

Archaeological evidence now suggests that Neolithic humans who grazed cattle on the Saharan pastures played a role as well. These pastoral communities pushed the delicate ecosystem past a tipping point that led to widespread desertification, according to a paper published in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science.

Study author David Wright of Seoul National University, South Korea, mapped the spread of scrub vegetation, which is a precursor to full desertification, and evidence of Neolithic cattle grazing. As more and more vegetation was removed from the land, the albedo – or amount of light reflected from the ground – increased, changing the atmospheric conditions over the Sahara. This in turn made monsoon rains less frequent.

About 8,000 years ago, cattle-grazing communities originated near the River Nile and began gradually to spread to the west of the continent. Rather than the spread of the communities happening in response to desertification and loss of vegetation, the humans could have been actively driving the desertification, Wright suggests.

"During the period when agriculture was adopted in northern Africa, the regions where it was occurring were at the precipice of ecological regime shifts," he writes in the paper. Cattle grazing could have been enough to push them over the edge, he said.

More data is needed to test the theory, and Wright believes that this will come from the remains of ancient lakes in the Sahara.

"There were lakes everywhere in the Sahara at this time, and they will have the records of the changing vegetation," Wright said in a statement. "We need to drill down into these former lake beds to get the vegetation records, look at the archaeology, and see what people were doing there."

The findings are not only of archaeological interest, but could lead to insights on how humans are driving and adapting to desertification today. Chronic hunger in countries bordering the Sahara desert, including Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti, is a result of desertification due to climate change and a lack of government action to address the problem, according to the UN Desertification Convention.

"The implications for how we change ecological systems have a direct impact on whether humans will be able to survive indefinitely in arid environments," Wright said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.