Does virus crisis stoke case for united Ireland?

Cooperation between the jurisdictions of Ireland and Northern Ireland has historically been a thorny matter.

Ireland's coronavirus crisis is often described as an "all-island" emergency, shared with the British territory of Northern Ireland -- a sign, some say, that the pandemic has bolstered the long-fraught case for unification.

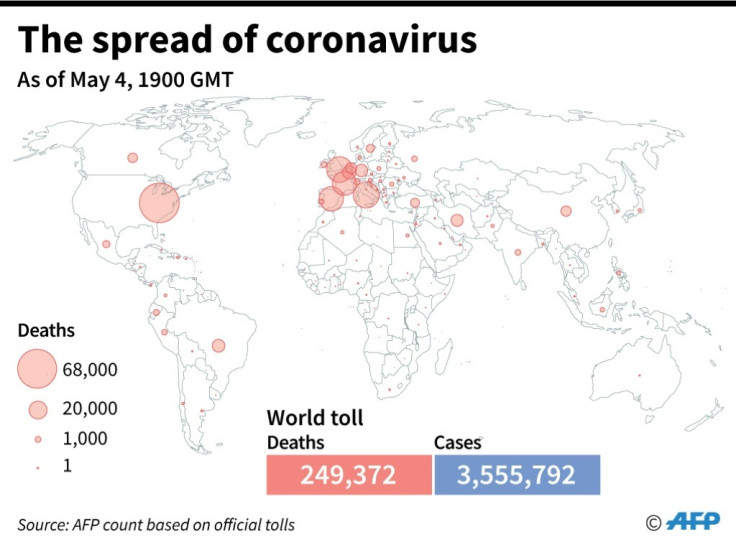

As the crisis has unfolded, death counts have often been tallied on an all-island basis -- a figure that stood at 1,684 at the start of this week.

"It knows no borders and we are all in this together," Irish Health Minister Simon Harris said as the contagion took hold last month.

"It is essential we continue to do everything we can across the island to fight this pandemic," he added.

In the decades-long debate over the destiny of Northern Ireland, his comments may be seen as freighted with particular meaning.

"Right now, people are viewing the question of Irish unity through the lens of epidemiology," wrote commentator Una Mullally in Britain's Guardian newspaper.

"The pandemic is many things, but it is political, and so too will be its consequences."

Cooperation between the jurisdictions of Ireland and Northern Ireland has historically been a thorny matter.

The British province to the north is traditionally divided between republicans who would gladly join the south and unionists who cherish links to the UK mainland.

Blood has been spilled over the divide -- 3,500 were killed in the three-decade-long conflict known as "The Troubles".

The violence largely ended in 1998 with a peace deal that created a devolved government for the province and included a clause to trigger a unity referendum in certain scenarios.

But relations between the two sides of the divide have remained fraught.

The COVID-19 emergency has rendered cooperation a medical necessity, however, as the disease spreads without regard for borders.

"It's a statement of fact that from an epidemiological point of view it makes sense for the island of Ireland to be as closely aligned as possible," Harris said as Dublin announced a plan on Friday to reopen the nation.

He said it was "not for any political reasons" and "purely from a public health point of view".

Even among Northern Ireland's most adamant unionists, there have been few publicly dissenting voices.

However, despite general promises to cooperate and coordinate, Northern Ireland and the Republic have taken different approaches to tackling the virus.

Ireland entered lockdown earlier and placed a strong emphasis on testing. In contrast, Northern Ireland followed Britain's less rigorous regime.

Some say the human cost of non-collaboration between the jurisdictions has become clear, as coronavirus cases surge in the Irish counties along the border with Northern Ireland.

The border county of Cavan now has an infection rate of 883 per 100,000 -- the highest in the nation ahead of even Dublin, according to data released Sunday by the Health Protection Surveillance Centre.

Gabriel Scally, president of epidemiology at the Royal Society of Medicine, told the Irish News that the lack of an all-island plan means "enormous risks" are being taken with lives.

"Data on COVID-19 in Northern Ireland is a black hole," he said.

"How do we find out why there are such high numbers of cases in border counties? Maybe there's spillover from the north. Who knows?"

Neighbouring nations the world over are wrestling with issues of alignment and coordination in the coronavirus crisis, most without debating issues of unification.

And the deference to science may be considered by many to be apolitical in contrast to the deeply political and emotional currents that will ultimately govern the question of Irish unity.

Eunan O'Halpin, of Trinity College Dublin, pointed to previous crises -- such as the 2001 foot-and-mouth disease outbreak -- which were dealt with on an "all-island" basis.

"You can have all the cooperation you like without having any political kickback from it," he said.

"This is a practical thing. It doesn't follow that unity is any closer."

Copyright AFP. All rights reserved.

This article is copyrighted by International Business Times, the business news leader