Election 2015: Ed Miliband lost Scotland forever during Question Time leaders' special

By accident or design, Ed Miliband furnished Scottish Labour with its very own "1979 moment" during his last Question Time, and helped lay the foundations for the landslide we saw in the election.

For the past 36 years, Labour has been able to claim the SNP was somehow responsible for Thatcherism, because it voted to topple James Callaghan's government on a motion of confidence in March 1979.

That's nonsense, of course – the vote simply brought the general election forward by a few short weeks and almost certainly didn't change the eventual outcome. But, to some extent, the legend has stuck. Labour has even attempted to get some mileage out of it in this very campaign.

And yet on the Question Time leaders' special, Miliband looked down the camera and told viewers he would rather let a Tory government take office than work with the SNP. This is 1979 on steroids.

Even more damaging for Miliband was his rationale for ostensibly preferring Tory rule, namely it would be unthinkable to offer a party such as the SNP any influence at all over the government of the UK.

SNP bends over backwards

Unfortunately for him, everyone in Scotland saw the SNP bend over backwards throughout this campaign to make itself a credible partner for Labour. Nicola Sturgeon and her party made clear they would act to provide good governance for the whole UK, not just for Scotland, and promised that even a clean sweep of Scottish seats would not constitute a mandate for an early second independence referendum.

In effect, the SNP eliminated each and every reasonable excuse for Labour to refuse to deal with them. When Miliband still insisted he wouldn't cooperate under any circumstances, the message Scottish voters heard, quite rightly, was: "Labour thinks there's one thing worse than Conservative rule, and that's the possibility of democratic Scottish influence over British affairs."

So what on earth was Miliband playing at? The most logical assumption is that he gave up entirely on Scotland and was targeting his message at English voters who, we were told, were scared of the idea of a distinctively Scottish party holding the balance of power, and might have been considering switching to the Tories as a result. But it never seemed quite as simple as that.

Miliband addressed Scottish voters directly on Question Time, implying they should heed his threat of putting the Tories in power and vote Labour to ensure he didn't do it. He truly seemed to believe out-and-out blackmail was likely to yield results, which raised serious questions over the quality of advice he was receiving.

First and foremost, anti-Tory voters in Scotland wanted to give their vote to a party that was actually committed to getting the Tories out of office. That decision became something of a no-brainer, given the SNP was clear it would seek to lock the Tories out in all circumstances and Labour was much more equivocal.

Bluffer hit the buffers

Some have suggested Miliband's words on Question Time were a gigantic conjuring trick, designed to reassure the English and bully the Scots, while not altering his actual stance at all.

It was noted that the only types of deal he explicitly ruled out were full coalition and a confidence-and-supply arrangement. In theory, this still left open the possibility of an informal – and most importantly deniable – vote-by-vote understanding with the SNP that would sustain a Labour minority government.

But there was a problem. Miliband couldn't have been much clearer that there are circumstances in which Labour would decline to take office to prevent SNP influence. Had this been impossible, his attempt to blackmail Scottish voters would have been, quite literally, meaningless.

We were left to assume that if the Conservatives were the largest party by a considerable margin, and if it was clear from the arithmetic that a Labour government would derive its legitimacy solely from the SNP's willingness to prop it up, Miliband would refuse a call from the palace.

This, however, would have entailed Labour abstaining on a Tory Queen's Speech, and being seen to actively install Cameron as prime minister. If the party had done anything else, it would be incumbent on Miliband's party to at least attempt to form a government, due to the provisions of the Fixed Term Parliaments Act.

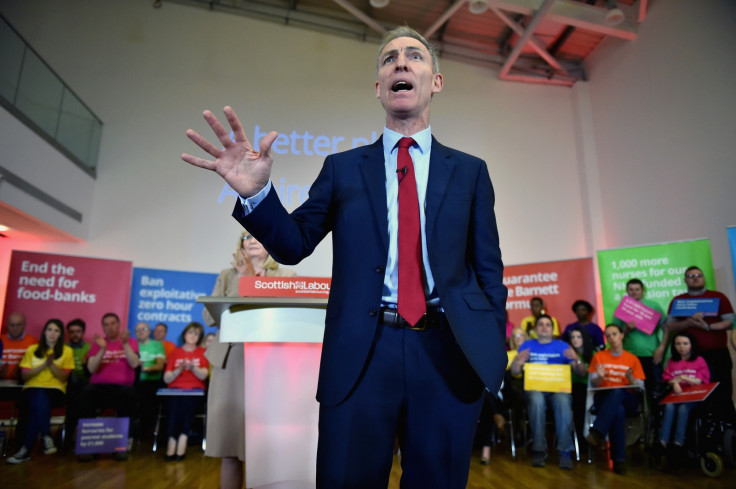

That dilemma - which, of course, is now redundant - was not helped by the fact that Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy was reluctantly coaxed by Nicola Sturgeon a few weeks before the election into confirming his party would definitely vote against a Tory Queen's Speech.

So the nationalists were left with a stark choice. Either Miliband was misleading us when he said there were some circumstances in which he would decline to seize power, or Murphy was misleading us when he said there were no circumstances in which Labour would refrain from voting down a Tory Queen's Speech. There wasn't a third possibility.

Perhaps Labour didn't even know which way they would jump. And, of course, it doesn't matter now. Miliband's strategy of clear, even if his public message was not. By the time Scottish Labour recovers from the fallout, it may be seeking power in an independent country.

James Kelly is author of the Scottish pro-independence blog, SCOT goes POP! Voted one of the UK's top political bloggers, you can hear more from James on Twitter:@JamesKelly

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.