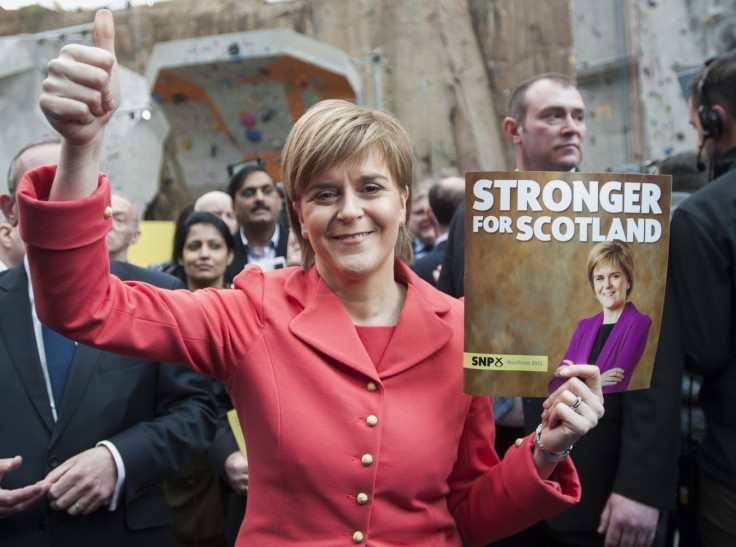

Election 2015: Who's afraid of Nicola Sturgeon?

Some 20 years ago, the BBC's Question Time was the setting for one of those very rare and special moments of destiny when two generations of political leadership unwittingly cross paths. It didn't quite have the historical resonance of a teenage Bill Clinton shaking hands with John F Kennedy, but it was about as close as you'll ever get to that within the political village of Scotland.

Donald Dewar, not long away from attaining his 'Father of the Nation' status by delivering devolution and becoming the original First Minister, was a member of the panel. He found himself being challenged by an indignant young woman in the audience, who demanded to know why Labour had abandoned its decades-long acceptance that the SNP could claim a mandate for independence if it ever won a majority of seats in the House of Commons.

Dewar patiently explained that it was possible to win a majority of seats without having a majority of votes, and that independence would require a much more unambiguous mandate than that, perhaps via a referendum. The suspiciously on-message SNP-supporting young woman was having none of it – wasn't it true that every Labour leader since Harold Wilson had said a majority of seats was enough? Who did Tony Blair think he was, shifting the goalposts now?

This was of course a case of one future First Minister challenging another, because the transparent SNP plant in the audience was fated to become known in some quarters as "the most dangerous woman in Britain" – or even (if you're Piers Morgan) "the most dangerous woman in the world". Back in those days, though, Nicola Sturgeon probably seemed more like a mild irritant to the SNP's opponents than any sort of threat. Dewar must have had a fair idea of who was taking him to task, because she was already well-known to TV viewers as the SNP's designated "youth person".

She would periodically pop up on our screens to intone the latest approved party platitude in the manner of an automaton, leaving the unfortunate impression of someone who rarely allowed a truly personal opinion to sully her thoughts. For one Party Political Broadcast, she was chosen to earnestly instruct bemused viewers on the SNP's new self-flagellating doctrine of maturity : if an election went the wrong way, it was either Scotland's own fault for not seizing control over its future, or it was the SNP's own fault for not making the case for independence effectively enough.

'She would periodically pop up on our screens to intone the latest party platitude in the manner of an automaton, leaving the impression of someone who rarely allowed a truly personal opinion to sully her thoughts.'

It was rather fitting that she ended up performing that role, because she was reputed to have made the decision to join the SNP after watching a Party Political Broadcast at the age of 16. An English journalist tweeted his bewilderment this week that Scottish Labour had failed to "spot" an obvious talent like Sturgeon at a young age, but that misses the point entirely – she had nailed her colours firmly to the mast long before talent-spotting in the university scene was even a theoretical possibility.

Her driving force was a sense of outrage at the devastation visited upon her own working-class Ayrshire community by the Thatcher government, and if that sentiment had led her to spontaneously join a party other than Labour in the prevailing climate of Scotland in the late 1980s, it's highly improbable that a tap on the shoulder would have made her see things any differently.

As the years wore on, Sturgeon subtly graduated from being the SNP's designated youth person to being its designated "next leader but one". Still in her mid-20s, she was selected to fight Glasgow Govan in the 1997 UK general election – a plum seat in the sense that it was the only one in the entire central belt of Scotland that the party was thought to have the slightest prayer of winning.

The Glasgow street fighter

Inevitably she fell short, but established her local legend as a street fighter by securing the only anti-Labour swing in the whole of Britain, as the Blair juggernaut swept all before it everywhere else. Her political home hasn't budged from that part of Glasgow in the years since.

'Miliband still comes across as a bit of a geeky weirdo lacking in leadership qualities, but less so than before. He has been confident and assured, seemed less rehearsed than usual in the debates, and is becoming more than just an abstract concept of a politician formed by the often unfavourable media reports about him.'

Read Shane Croucher's take on the 'sexing up' of Ed Miliband here.

By 2004, her ultimate destiny seemed to have caught up with her at lightning speed. Alex Salmond's successor John Swinney had been left with little option but to resign after failing to connect with the electorate, and in line with what had always seemed to be the long-term plan, the party hierarchy queued up to support Sturgeon's candidacy as leader. But she was only 34, and some of the SNP rank-and-file reacted with unease – they still saw the automaton and not the conviction politician underneath.

As the campaign progressed, it became abundantly clear that she was on course to be beaten by the more experienced Roseanna Cunningham. It was equally clear from a number of shaky TV performances that Cunningham was highly unlikely to lead the party to victory in the 2007 election. In a stunning bid to rescue the situation, Salmond announced just hours before nominations for the leadership closed that Sturgeon had agreed to withdraw in his favour, and instead stand for deputy as his running-mate.

So how precisely has Sturgeon gone from being effectively rejected by her party just one decade ago to becoming the undisputed queen of the entire pro-independence movement? And how has someone whose life story appears at first glance to be that of an archetypal career politician managed to earn such overwhelming warmth and affection from the public at large?

I think the answer to both questions lies in her modest background. As her communication skills blossomed in her late 30s and early 40s, many people recognised something of themselves in her – the person who took herself a touch too seriously in her youth, but was now comfortable in her own skin.

It's so much easier to identify with a working-class girl made good from Irvine than it is with a Cameron or Miliband, and it's certainly far, far easier to accept that she remains firmly grounded in the real world, in spite of barely having worked outside politics at any point in her life. Even the widely-reported shedding of her former geeky image has the feel of authenticity – rightly or wrongly, the injection of glamour from dress designers Totty Rocks comes across as an extension of the newly-liberated fun side of her personality, rather than something she has felt compelled to do out of political calculation.

If she ever finds her mind drifting back to that fateful encounter with her predecessor Donald Dewar, she might well reflect on the irony that the Nicola Sturgeon of 2015 would wholeheartedly agree with the argument Dewar used against her younger self.

She is absolutely clear these days that a majority of Scottish seats in the Commons is not in itself a mandate for independence. But the biggest irony of all is that she is the person who has at last taken the SNP to the brink of the supreme achievement of securing that majority – and she will also ultimately shape and define what the true meaning of that breakthrough is.

Mini-bio : James Kelly is author of the Scottish pro-independence blog, SCOT goes POP! Voted one of the UK's top political bloggers, you can hear more from James on Twitter:@JamesKelly

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.