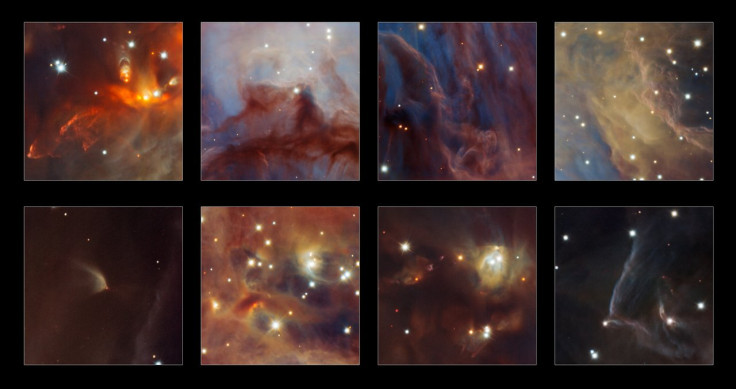

ESO's Very Large Telescope gives most detailed view of Orion Nebula ever seen

Spectacular view of Orion Nebula reveals 10 times more brown dwarfs and low-mass objects than were known.

A spectacularly detailed view of the Orion Nebula has been released, revealing a plethora of brown dwarf stars and – tantalisingly – the potential for many planet-sized objects. Scientists used the ESO's Very Large Telescope to peer deep inside Orion in the hopes of better understand the process and history of star formation.

The Orion Nebula sits in the constellation of Orion. It is 24 light years across and is visible with the naked eye from Earth – it is the fuzzy patch seen on Orion's sword. The nebula is particularly bright because of the ultraviolet radiation from the multitude of hot stars being born within it.

However, just how many stars and other planetary-mass objects there were inside it was not well known. In a study published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, an international team of scientists said the images returned from the VLT indicate a far higher number of brown dwarfs and potential planets than previously thought.

Indeed, they found 790 brown dwarf candidates and 160 isolated planetary mass object candidates (objects that could be planets) – "about ten times more substellar candidates than known before", they wrote.

The discovery suggests the Orion Nebula may be producing far more low mass objects than other closer and less active star formation regions. This, scientists say, will help them better understand how and when stars form. Study co-author Amelia Bayo explained: "Understanding how many low-mass objects are found in the Orion Nebula is very important to constrain current theories of star formation. We now realise that the way these very low-mass objects form depends on their environment."

While the VLT cannot be used to observe these low-mass objects and potential planets, the ESO's future European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) – which will begin operations in 2024 – will be able to. Lead scientist Holger Drass said: "Our result feels to me like a glimpse into a new era of planet and star formation science. The huge number of free-floating planets at our current observational limit is giving me hope that we will discover a wealth of smaller Earth-sized planets with the E-ELT."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.