Fidel Castro's shadow grows fainter as young Cubans choose cash and life over 'socialism or death'

Raul Castro's tin-pot police state has replaced his brother's Orwellian cult of personality.

Ten years ago, when the Cuban leader Fidel Castro turned 80, it was widely assumed that he was about to depart this mortal coil. I was in Havana at the time, and the preparations which the Cuban government had been diligently making for Castro's birthday had been abruptly halted.The figure which had dominated Cuban life for half a century had suddenly been taken severely ill with gastro-intestinal bleeding.

But rather than celebrating, as some outside the country might have expected of a people living under a communist dictator for half a century, the mood was subdued and vaguely fearful among the Cubans I spent time with. As a young Havana resident whose house I was staying in told me with visible trepidation. "His brother Raul is worse. He's a real military man."

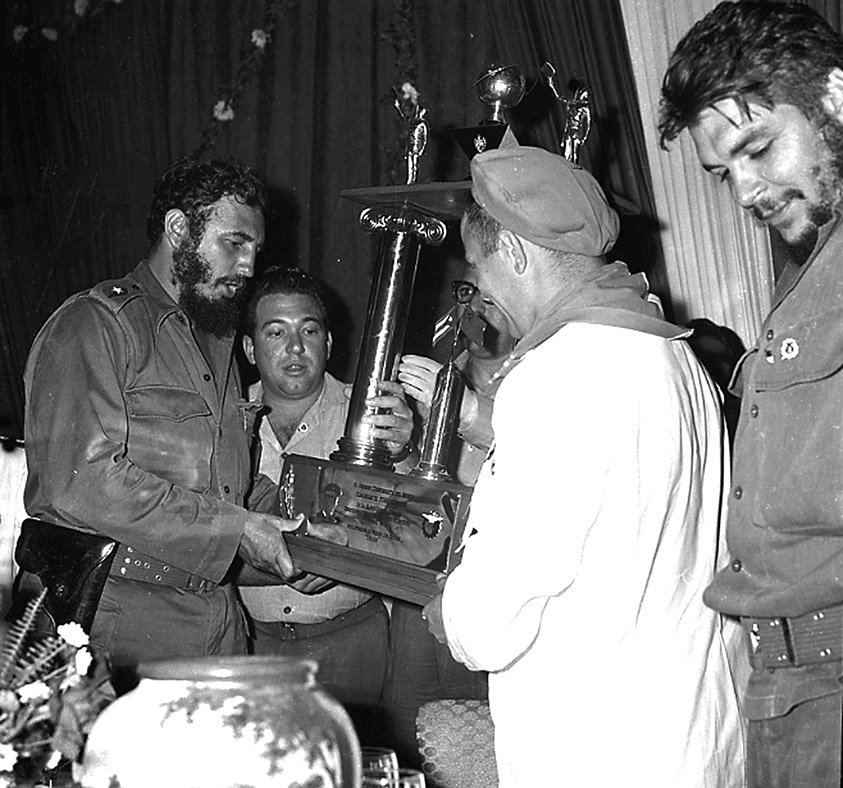

The popular view of current Cuban President Raul Castro as a doctrinaire hardliner – in contrast to the benevolent and charismatic Fidel - was acquiesced in by the Castro brothers during the decades after the 1959 revolution. Thus when Fidel was threatened with assassination by the CIA in the 1960s, he warned that 'behind me come others more radical than me' - widely assumed to be a reference to his younger brother Raul, the moustachioed defence minister.

There was of course a good deal of substance to the image of Raul Castro as the military hardman – or 'the little helmet', as some Cubans called him. Along with Ernesto 'Che' Guevara, Raul was one of the leaders of a small group of hard-line Stalinists within the 26th of July revolutionary movement during the earliest days of the Cuban revolution – a faction which ultimately triumphed over more liberal currents in the revolution. Raul was also alleged to have presided over the summary execution of 70 captured Batista soldiers during the revolutionary war, mown down with machine guns in front of an open trench near Cuba's second city Santiago de Cuba.

Yet, since assuming power temporarily in 2006 (and permanently in 2008) Raul has demonstrated the greater ideological flexibility of the two brothers. In the decade since Fidel's 80th birthday, Cuba has undergone probably a greater degree of change than in the previous 40 years combined. Hundreds of Cubans are now running private businesses, farming their own land and using cell phones and the internet. They are also allowed to travel overseas and stay in luxury hotels which were previously reserved for tourists (though the price is prohibitively expensive for most).

Fidel came to communism late (he didn't openly declare his allegiance until 1961) but it took Raul, the Cuban revolution's little Stalin, to move away from the failed command economic model which had impoverished Cubans when the subsidies from the Soviet Union disappeared in the early 1990s.

I travelled to Cuba again last year and there was still the museum piece air about the place - the Cadillacs purring along the Malecon; the salsa and cigar smoke wafting out of every fly-blown little bar – but the air in Havana felt a fraction more breathable than it had a decade before. Even in those areas of life where things hadn't changed a great deal – the average Cuban salary remained pitifully low at $25 a month - there was a palpable sense that the country was tentatively breaking out of its 50-year state of chrysalis.

Encouragingly, and despite the continued harassment of dissidents, I was told by Erasmo Calzadilla, a left-wing writer for the independent Havana Times website, that since Raul assumed office there had been a 'gradual disappearance of an atmosphere of fear mixed with the personality cult built around the 'Great Leader'. Less Nineteen Eighty-Four and more run-of-the-mill tin-pot police state, but not to be sniffed at all the same.

Cuba's young show little interest in the old slogans calling for 'socialism or death'

In a revealing interview which Che Guevara gave a French newspaper in 1963, he was clear that Cuba's commitment to the eastern bloc was "half the fruit of constraint and half the result of choice". Guevara and Raul Castro favoured the Soviet model quid quid accidit, whereas Fidel saw the Leninist one-party state (with its tentacles in every corner of Cuban society) as the surest way of shoring up his own tendency towards caudillismo. The United States, which was unwilling to tolerate even the most anaemic strand of Latin American leftism in the 50s and 60s, acted in such a way that an early rupture with the Castro government was inevitable.

But since Fidel nationalised the Cuban economy in the early years, politics on the island has been largely reactive, and has zig-zagged between repression and tentative openings. Events have dictated each sharp turn like a rudder steering a ship. Thus Cuba opened up a little to see off the 'special period' of hardship in the 1990s, only to clamp down violently on dissent in 2003 when the worst of the economic crisis had passed (during the 'Black Spring' of that year 75 journalists and human rights activists were rounded up and sentenced to lengthy prison terms).

Since Raul assumed office, another liberalisation has taken place. But with the ongoing economic meltdown in Venezuela, which provides Cuba with millions of barrels of heavily discounted oil, the country is facing yet another period of severe austerity.

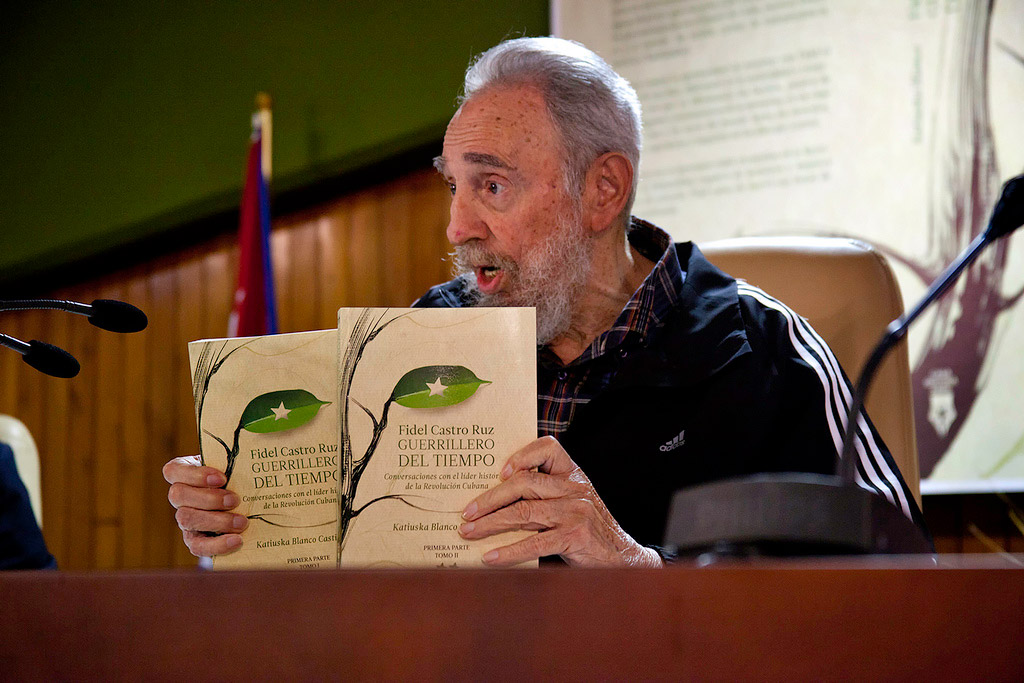

In his 2011 novel Tulum, the American writer David Seth Michaels remarks that if you turn on the television set in Cuba and see Fidel answering questions – rather than advertisements for McDonald's and Pepsi – you know the revolution is still in place. Va bien.

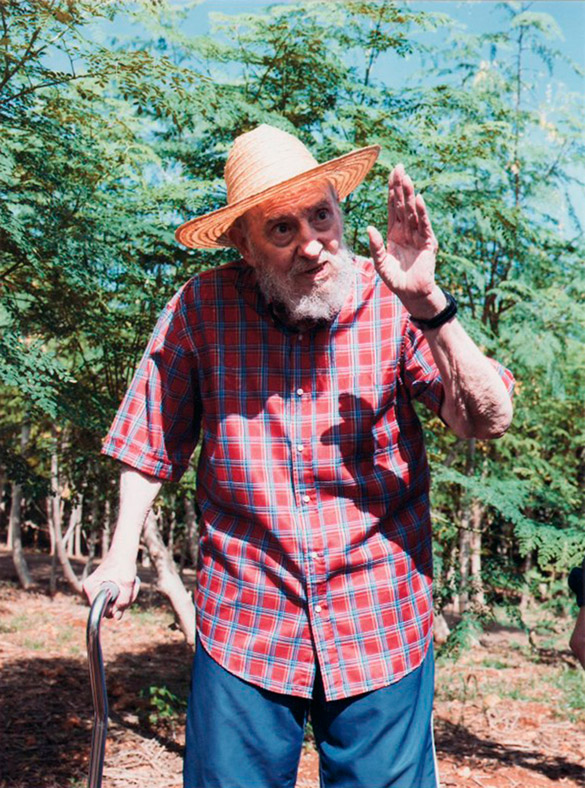

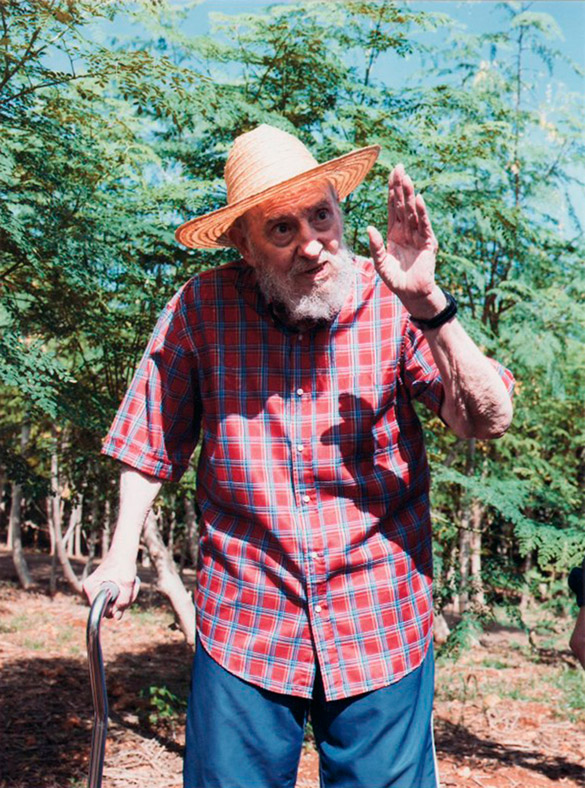

But Fidel in Cuba today is more like a shadow - a shadow which gets gradually fainter every year. A wizened old man may occasionally appear in photographs in the state newspaper, jabbing a mottled hand at foreign dignitaries, but the big combative solipsist who used to bestride the lectern in olive-green fatigues and harangue the Cuban people for one last sacrifice is gone; the only place he exists today is in the grainy archive footage played on state television in the interludes between loud and vacuous American movies.

Cuba's young show little interest in the old slogans calling for 'socialism or death'; they want whatever system puts enough money in their pockets for a new pair of jeans and a night out listening to reggaeton. The old question, then, remains about the most pertinent one as Fidel hangs on for another year: with another economic crisis imminent, can the revolution survive the evanescence of a man who, until a decade ago, involved himself in nearly every aspect of Cuban life?

James Bloodworth is former editor of Left Foot Forward, one of the UK's top political blogs, and the author of The Myth of Meritocracy.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.