Forensic science to reveal sex of prehistoric cave artists

A mock cave was used to test how good forensic scientists are at identifying artists' sex from hand stencils.

The artists who spattered paint around their hands placed on cave walls 40,000 years ago can now be identified as either male or female.

A new method borrows techniques from forensic science to find out a stencil artist's sex with 90 per cent accuracy, according to a paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

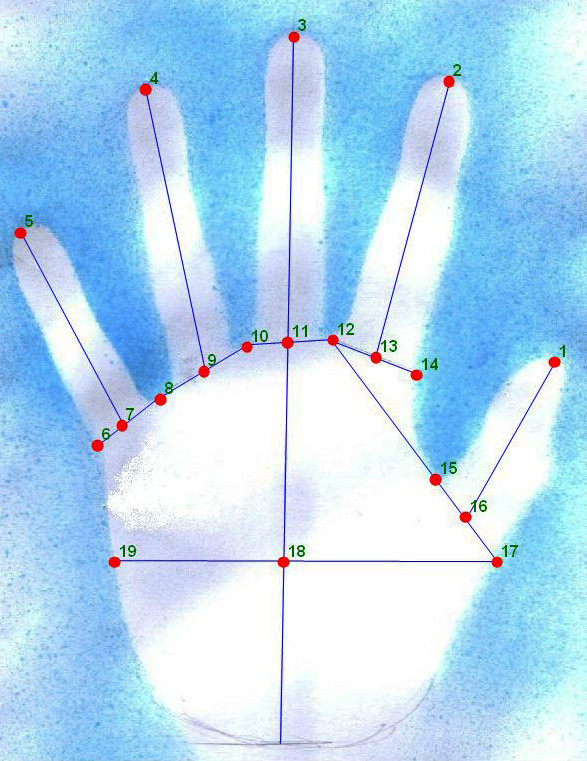

Modern-day volunteers did a bit of stencil art as part of the study, and the researchers then used a technique called geometric morphometrics – measuring a host of ratios and sizes of features of the hand – to work out from the stencils whether it was a man or woman who made it.

Mock prehistoric cave

Participants spattered poster paint around their hands to leave a stencil mark on a mock cave wall.

The researchers used the stencil to map features such as the points between fingers, the width of the base of fingers, the distance from the base knuckle of the thumb to the outer edge of the palm and the tips of the fingers of the study participants.

The mock cave helped make the hand stencil simulations more realistic and to see how the stencils look under different lighting, and proved popular with participants and the public.

Analysis of the distances between these features allowed researchers to predict with 90 per cent accuracy whether the stencil was made from a woman's hand or a man's hand.

The technique is a promising step towards understanding how Palaeolithic people across the world were making cave art. Hand stencilling was a popular Palaeolithic pastime: prints on rock surfaces have been found in the Americas, Africa, Arabia, Australia, east and south Asia and Europe.

A physical connection to the past

"Archaeologists are interested in hand stencils because they provide a direct, physical connection with an artist living more than 35,000 years ago," says Emma Nelson of the University of Liverpool in the UK, who led the study.

Geometric morphometrics also gets around the problem of hand prints where the artist had a digit missing – not such a rare occurrence tens of thousands of years ago. Previous attempts to determine the sex of these ancient artists relied on factors such as digit length and overall hand size, which were harder to estimate when fingers or thumbs were missing.

"This geometric approach is very powerful as it allows us to look at the palm and fingers independently," says Patrick Randolph-Quinney, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Central Lancashire in the UK and the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, who was also a study author.

"It revealed that the shape of the palm is actually most indicative of the sex of the individual, rather than the finger size or length."

As the application of geometric morphometrics to Palaeolithic cave art is a new step, the authors say that broader studies need to be done to factor in subjects of different ethnicities, as more than 90 per cent of the study's participants at Liverpool were white Caucasian. When the technique has been honed and standardised, it will be possible to apply it directly to ancient cave art to determine the artists' sexes.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.