Greek debt crisis: Greece takes axe to bloated pension system with retirement age hike to 67

Greece has pledged to raise its retirement age to 67 as part of a deal to avoid exit from the European Union, the latest reform to its bulging pension system that once saw hairdressers and TV presenters classified as "dangerous" professions and able to retire at 50.

As a result of years of concessions to trade unions by Greek governments, pensions were worth 17.5% of GDP in 2012 with one in five Greeks over the age of retirement. The government has already raised the age from 60 to 65 in return for bailouts from the EU.

It also acted to end to a system that saw as many as 580 professions listed as "arduous" and/or "dangerous" and therefore able to retire early, sometimes at the age of 50 for women and 55 for men. This included factory workers but also hairdressers (who work with chemicals) and TV presenters (who risk picking up germs from their microphones).

Vasilios Alevizakos, a political consultant and former director of the political office of the deputy minister and the ministry for foreign affairs in Athens until 2014, said that many of these jobs were struck off the list as part of a deal with Greece's EU creditors in 2012. As a result, the list of arduous professions has been reduced to around 100.

He said that TV presenters and hairdressers are no longer included in the list, which is now limited to dangerous professions, such as those that work with chemicals.

The government of Alexis Tsipras estimates that raising the age of retirement to 67 by 2020 would bring permanent savings of 0.25% to 0.5% of gross domestic product in 2015 and 1% from 2016, but its impact is more symbolic than anything. Greece's generous retirement system has long aroused anger in other European nations.

Spain too agreed to raise the retirement age to 67 earlier this year as it aims to reduce pension spending by around 3.5% of GDP by 2050. Italy has pledged to raise retirement age to 68 before 2050 (it is currently between 60 and 65). Germany is going the other way, reducing the retirement to 63 for some civil servants in 2014.

Alevizakos said that the retirement age has been one of the most contentious concessions by Tsipras, especially given that the Syriza leader had previously said that it was one of Greece's "red lines". The government has also pledged to end the EKAS grant system that the saw the pensions of the poorest retired Greeks topped up by government funds.

"It is definitely one of the most controversial aspects... as in the past Tsipras said that we would not even discuss it," he said.

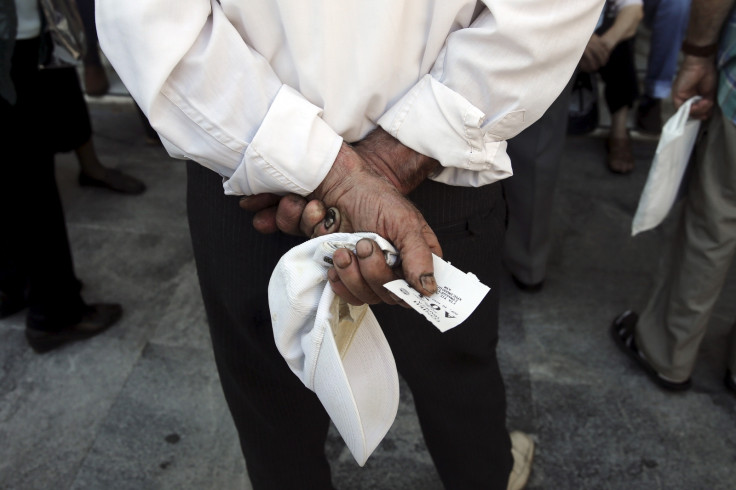

The cuts so far have been substantial, according to Greece's largest labour union, with the average pension totalling €833 (£600, $915) a month in 2015, compared with €1,350 (£731, $1,484) in 2009. At the same time, Greek pensioners are comparatively young. In 2012, the average age Greeks got their first pension was 57.8, compared with 59.6 for the Eurozone.

Itek Ozkardeskaya, a market analyst at London Capital Group, said that Greece's economic woes were clearly having a dramatic effect on pensioners in the short term, but that in the long term the impact of raising the retirement age would be minimal. This is because if and when Greece emerges from the crisis, its entire labour system will likely need to be reformed.

"The financial impact is not going to be huge in the long term," she said.

For Alevizakos, who lives in Athens and earlier this week told IBTimes UK how dramatic an impact the crisis was having on his life, there is a certain degree of anger that the government has proposed concessions that amount to €13bn (£9.4bn, $14.7bn) worth of cuts when the original deal offered to the government in February was only €1.2bn (£865m, $1.3bn) and two weeks ago was €8.5bn (£6.1bn, $9.5bn).

At the same time, he accepts that the pension reforms and the raising of the retirement age is essential to end the absurd system by which the government had topped up the coffers of Greek pension funds in order that they could pay out to Greek pensioners, as those same funds invested in Greek government debt that was progressively worthless.

"It is a difficult system but the fact is that the Greek pension system is bankrupt and the money has to come from somewhere. For decades now the government budget has been making up the difference between what the pension funds had and what they needed to pay out," he said.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.