How do volcanic arcs get their magma?

Lavas form when 'mélange' metamorphic rocks melt under volcanic arcs, geologists argue.

Evidence has been found to support a theory of how lavas form under volcanic arcs that was thought to be "fantasy" for decades.

How volcanoes in arcs – such as the famous Ring of Fire in the Pacific Ocean – get their lava was thought to be a fairly straightforward process. These strings of volcanoes stretching for many miles form along the boundary where one oceanic plate is forced underneath another plate.

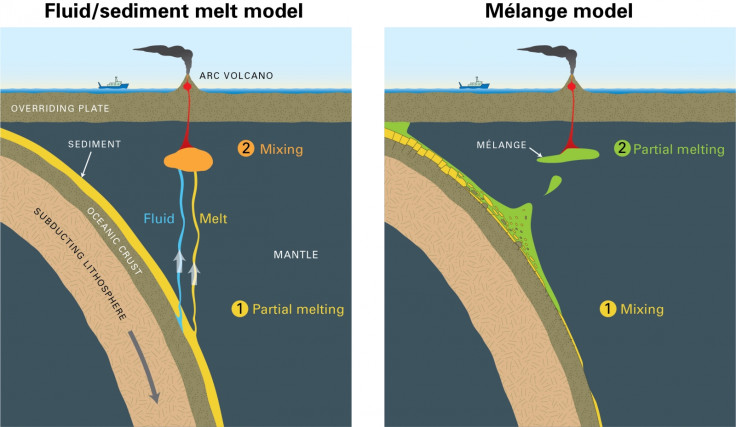

Traditionally it was thought that the sediment at the subducted plate would melt at its edge, and then start to rise back up through the mantle. This would then trigger more melting and mixing of rock in the mantle. Eventually, enough pressure would build up that the molten rock would force up through the crust and out to the surface in a volcanic eruption.

However, a study published in the journal Science Advances reports that the melting of 'mélange' rock, which is formed under very high temperatures and pressures at the subducted plate edge is the source of the magma.

The melting of these mixed metamorphic rocks was not thought to be the source of rising magma. But a low-density patch of mélange rock – called a diapir – could rise to the surface beneath volcanic arcs, argues study author Horst Marschall of Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany.

"The mélange-diapir model was inspired by computer models and by detailed field work in various parts of the world where rocks that come from the deep slab-mantle interface have been brought to the surface by tectonic forces," Marschall said in a statement.

"We have been discussing the model for at least five years now, but many scientists thought the mélange rocks played no role in the generation of magmas. They dismissed the model as 'geo-fantasy.'"

Analysing the composition of rocks at volcanic arcs worldwide, the authors argue that the mélange model describes how magma forms under the volcanoes better than the traditional model.

"A large fraction of Earth's volcanic and earthquake hazards are associated with subduction zones, and some of those zones are located near where hundreds of millions of people live, such as in Indonesia," said study author Sune Nielsen of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the US.

"Understanding the reasons for why and where earthquakes occur, depends on knowing or understanding what type of material is actually present down there and what processes take place."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.