How UK Income Tax Quirks Make Some Workers Worse Off

You might not realise it, but some of you are stuck in the income equivalent of quicksand.

That's because there are parts of the UK's tax and benefits system that aren't linked to inflation.

So some tax and benefit bands don't rise at the same pace as wages often do.

This means that the real terms value of the wages at each tax and benefit band falls as inflation rises.

And those who hit such particular bands are then swallowed by the removal of benefits or higher tax, despite their incomes being worth less than those affected even just a year before.

It is an anomaly in the system highlighted by Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) thinktank, in his latest paper "Tax Without Design: Recent Developments in UK Tax Policy":

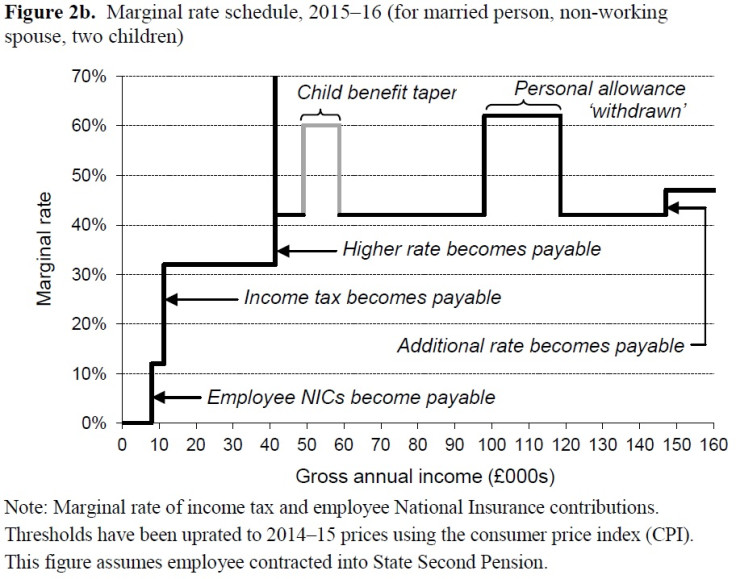

The band for the withdrawal of child benefit is fixed between £50,000 and £60,000. The point at which the personal allowance starts to be withdrawn is fixed at £100,000 – and as the level of the personal allowance has increased, the band of income to which a 60% tax rate applies has therefore continued to grow.

The £150,000 point at which additional-rate income tax starts to be paid is also fixed. The result is that, in real terms, the point at which these two higher marginal rates bite will, by 2015–16, have fallen by 12% (relative to the CPI) since they were introduced in 2010–11.

There was a good reason for default indexation of allowances and thresholds. Chancellors looking to fill their coffers as a result of fiscal drag will no doubt enjoy the effects of the lack of indexation of these new thresholds, but this looks like a move away from rational design.

Just to explain the 60% tax rate and the personal allowance for a moment – when an individual hits £100,000 a year, the personal allowance (the amount someone can earn before they start paying income tax) is taken away. So they pay income tax on every penny of their earnings.

The UK income tax rates for 2014/15.

Personal Allowance: £10,000

Basic Rate: 20% | £0 - £32,010

Higher Rate: 40% | £32,011 - £150,000

Additional Rate: 45% | Over £150,000

This, until they earn enough that the effect of removing the personal allowance has gone, puts them at an effective 60% tax rate.

So as the personal allowance is increased by the government, those earning over £100,000 have to take home even more to escape the effective 60% rate before it evens out to a 40% income tax rate again.

In 2009/10 the personal allowance was £6,475. It meant that there was an effective 60% income tax rate between £100,000 and £113,000.

In the 2014/15 tax year it is £10,000 – meaning a marginal 60% rate from between £100,000 and £121,000 before the earner has caught back up with the cost of losing the allowance.

After this the effective rate becomes 40% again until the top rate (called "additional"), at which the band is £150,000 and earnings above are taxed at 45%.

"There is no plausible rationale for a rate structure that looks like this," said Johnson of the IFS.

'Who designed that?'

Johnson also bemoans the other quirks of a tax system in which various tinkering has been made over the years, but without any overall holistic vision for how it should work – creating a haphazard cacophony of oddities.

For example, the employer national insurance contribution (NIC) increases each year by the Retail Price Index (RPI) measure of inflation.

But the employee NIC – the one people pay out from their salaries – goes up by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation measure.

"Who designed that?" asks Johnson.

What's more, he highlights the peculiarity of the tax break for married couples. This policy, a favourite of Prime Minister David Cameron, comes into effect if two spouses are paying the basic rate of income tax and one is earning below the personal allowance threshold.

The rest of the allowance – up to a cap of £1,050 – transfers over to the higher earning spouse as a tax break.

But as soon as one starts paying the higher tax rate, this allowance transfer is cancelled.

As Johnson points out:

The effect is that the additional £1 of income that takes this person into higher-rate tax will result in an additional £210 tax bill. This amount may be relatively small, but it never makes sense to have this kind of thing in a tax schedule. Perhaps more importantly, it looks like an indication of a lack of direction. Introducing a transferable allowance for married couples is a substantive change to the tax system.

It is a move back towards a degree of joint taxation. The amount that can be transferred is set at just £1,050 – worth £210 a year or £4 a week to the 30 per cent or so of married couples set to gain. Introduction on such a modest scale may make sense to keep initial costs down.

But introducing the transferable allowance in a way that will make it extremely hard to extend without making this cliff edge at the higher-rate threshold worryingly high smacks of a lack of long-term design.

A chart in the IFS report highlights just how erratic the tax and benefits system looks, though it does not include every welfare payment available.

Ultimately, despite the "huge political pressures" surrounding tax changes, Johnson urges policymakers to make the system simpler and to engage honestly with the public and experts as they do it.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.