Mice turned into zombie killing machines with special laser beam

Optogenetics used to target area of the brain related to emotion and motivation to trigger hunting behaviour.

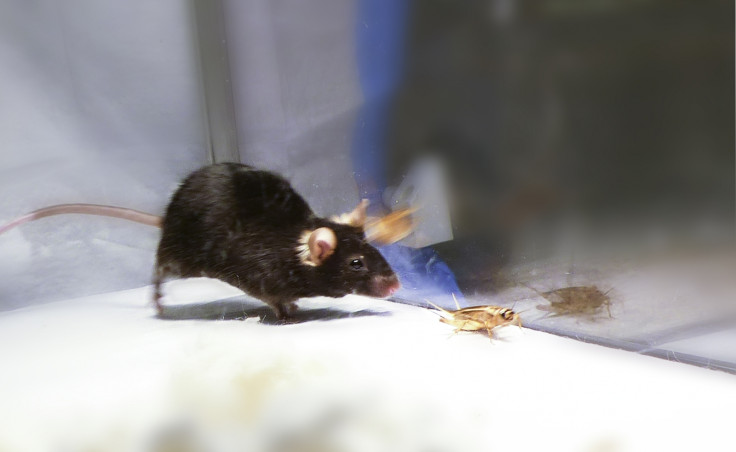

Mice have been turned into zombie-like killing machines by firing a laser beam at the area of the brain involved in emotion and motivation. Researchers at Yale University used optogenetics to trigger the mice to hunt and kill prey – and they say the same response could be created in other animals, including humans.

The team, led by Ivan de Araujo, targeted a set of neurons in the amygdala. They then targeted these neurons and fired a light at them, isolating and activating each set. When they did this, the mice – which had been behaving normally – began hunting and attempting to kill inanimate objects and live insects. "We'd turn the laser on and they'd jump on an object, hold it with their paws and intensively bite it as if they were trying to capture and kill it," de Araujo said.

Does this mean we could create an army of killer mice? Potentially, de Araujo said – but they would probably not be work together on a path of destruction: "We believe that the behaviour we elicited was specific to predation in the sense food seeking," he told IBTimes UK. "So one could in theory assemble groups of mice that will perform hunting more efficiently (always considering the huge difficulties of performing such experiments outside a lab). But I do believe that they would not act as a group and would individually forage for prey."

The research, published in the journal Cell, was primarily looking at what drives feeding behaviours in animals. Understanding what drives animals to hunt for food will help shed light on the evolution of predatory behaviour, and why jawed vertebrates (like us) became so successful.

"It is a major evolutionarily player in shaping the brain," de Araujo said. "There must be some primordial subcortical pathway that connects sensory input to the movement of the jaw and the biting."

The team mapped the brain areas related to hunted and feeding and they found one that was associated with predation alone. They then looked at each neuron and found specific ones were associated with hunting alone – when they triggered this with the laser, the mice would pursue the prey but not kill it. This shows the laser does not trigger aggression generally – it is aggression purely related to feeding.

When all the neurons were fired on, the mice would hunt down and kill anything in their way, such as bottle caps, wooden sticks and insects. They did not, however, turn on each other – something de Araujo and his team cannot explain: "We don't know but are interested in this question. But the general mechanism must involve a brain region that detects the presence of a conspecific and inhibits central amygdala."

Asked whether the same neurons could be activated in other species to illicit a hunt/kill response, de Araujo said: "In theory, one could elicit foraging/hunting for food in other species as this region is conserved in primates including humans. I do however stress that the behaviour seems specific to hunting for food, so any effects would be associated with hunting activities, not aggression per se –for example against other humans."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.