Monstrous 163-million-year-old crocodile discovered, shedding new light on ancient reptile evolution

Fossil belonging to the 'Melksham Monster' sat in the archives of the Natural History Museum for nearly 150 years.

Palaeontologists have identified a 163-million-year-old marine predator that sheds new light on the evolutionary history of modern crocodiles.

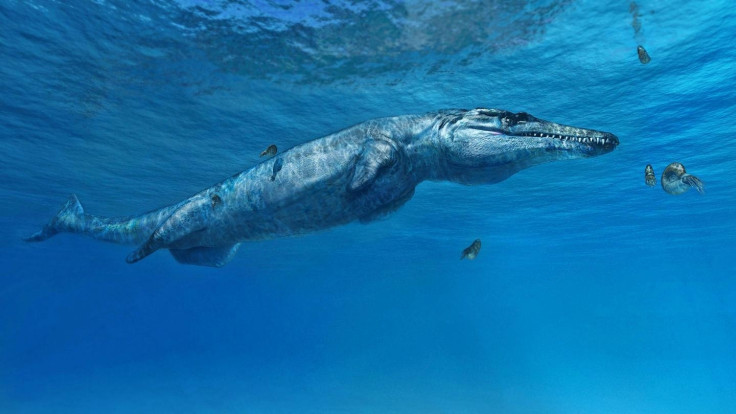

The new species was a 10ft aquatic reptile with powerful jaws and fearsome, serrated teeth, which would have allowed it to eat large prey such as prehistoric squid. It is thought to have lived in the warm, shallow seas that covered much of what is now modern-day Europe.

Researchers from the University of Edinburgh identified the new species by examining a heavily damaged fossil that had been sitting in the Natural History Museum's archives for almost 150 years.

The animal has been named Leldraan melkshamensis – or the Melksham Monster – after the town in England where it was first unearthed.

"The Melksham Monster would have been one of the top predators in the oceans of Jurassic Britain, at the same time that dinosaurs were thundering across the land," said Steve Brusatte, who was involved in the study.

The discovery reveals that the sub-family of aquatic reptiles to which the new species belongs – the ancestors of modern crocodiles, known as Geosaurini – evolved millions of years earlier than previously thought.

Until now, it was thought that Geosaurini originated in the Late Jurassic Period, between 157 and 152 million years ago. But the new findings, in conjunction with the re-analysis of existing fossil evidence, suggests that the sub-family arose millions of years earlier during the Middle Jurassic period. The study was published in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

"It's not the prettiest fossil in the world, but the Melksham Monster tells us a very important story about the evolution of these ancient crocodiles and how they became the apex predators in their ecosystem," said Davide Foffa, the leader of the study. "Without the amazing preparation work done by our collaborators at the Natural History Museum, it would not have been possible to work out the anatomy of this challenging specimen."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.