Moon for sale? US government says Bigelow Aerospace could set up lunar base with land rights

The United States government has taken a tentative step towards allowing commercial development of the moon by private companies.

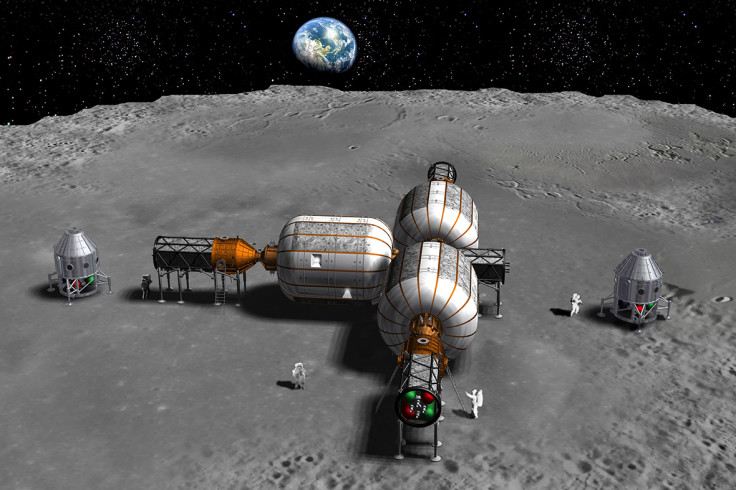

In a letter to Bigelow Aerospace, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) said the company could set up one of its proposed inflatable habitats on the moon, and expect to have exclusive rights to that territory - as well as related areas that might be tapped for mining, exploration and other activities.

However, the letter did note that "the national regulatory framework, in its present form, is ill-equipped to enable the US government to fulfill its obligations" under the 1967 United Nations Outer Space treaty, which, in part, governs activities on the moon.

The UN treaty requires countries to authorise and supervise activities of non-government entities that are operating in space, including the moon. It also bans nuclear weapons in space, prohibits national claims to celestial bodies and stipulates that space exploration and development should benefit all countries.

The FAA letter's author George Nield said: "We didn't give [Bigelow Aerospace] a licence to land on the moon. We're talking about a payload review that would potentially be part of a future launch license request. But it served a purpose of documenting a serious proposal for a US company to engage in this activity that has high-level policy implications."

Robert Bigelow, a Las Vegas-based construction contractor, real estate mogul and hotel businessman, said he intends to invest $300m (£199m) of his own funds, about $2.5bn in hardware and services from Bigelow Aerospace and raise the rest from private investors.

The FAA's decision "doesn't mean that there's ownership of the moon," Bigelow said. "It just means that somebody else isn't licensed to land on top of you or land on top of where exploration and prospecting activities are going on, which may be quite a distance from the lunar station."

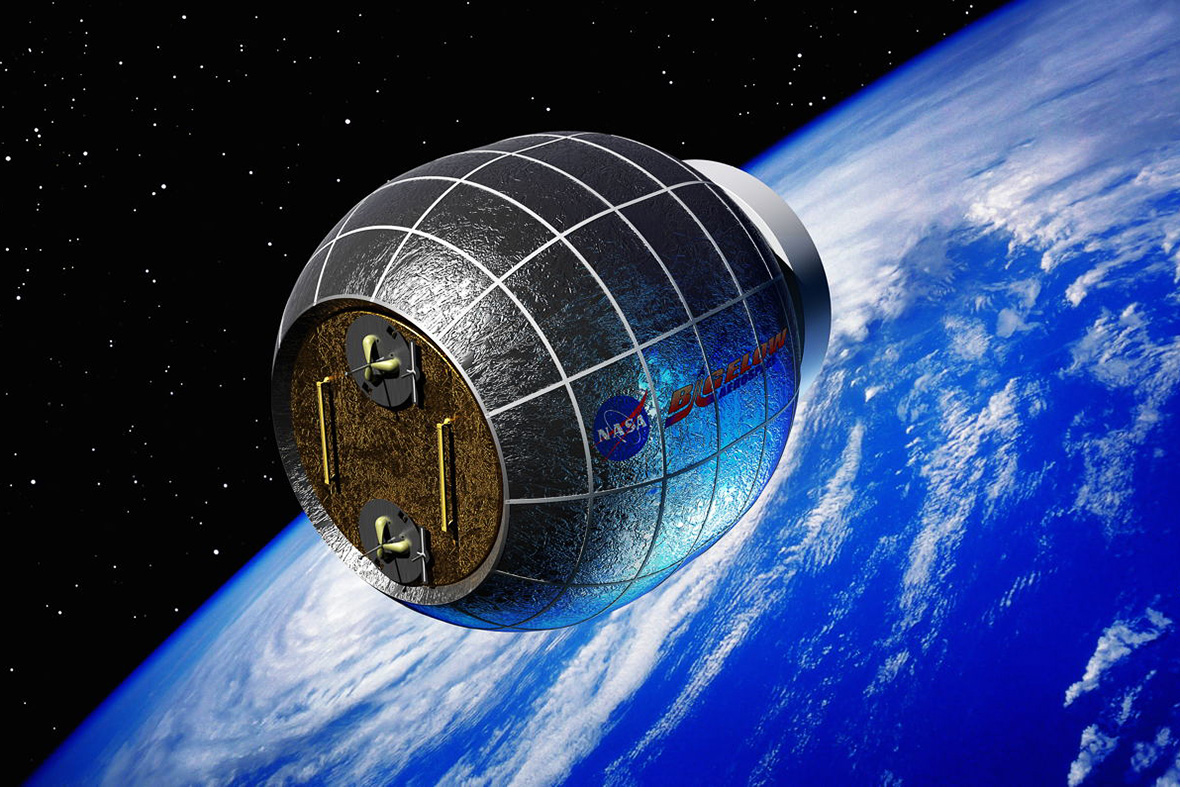

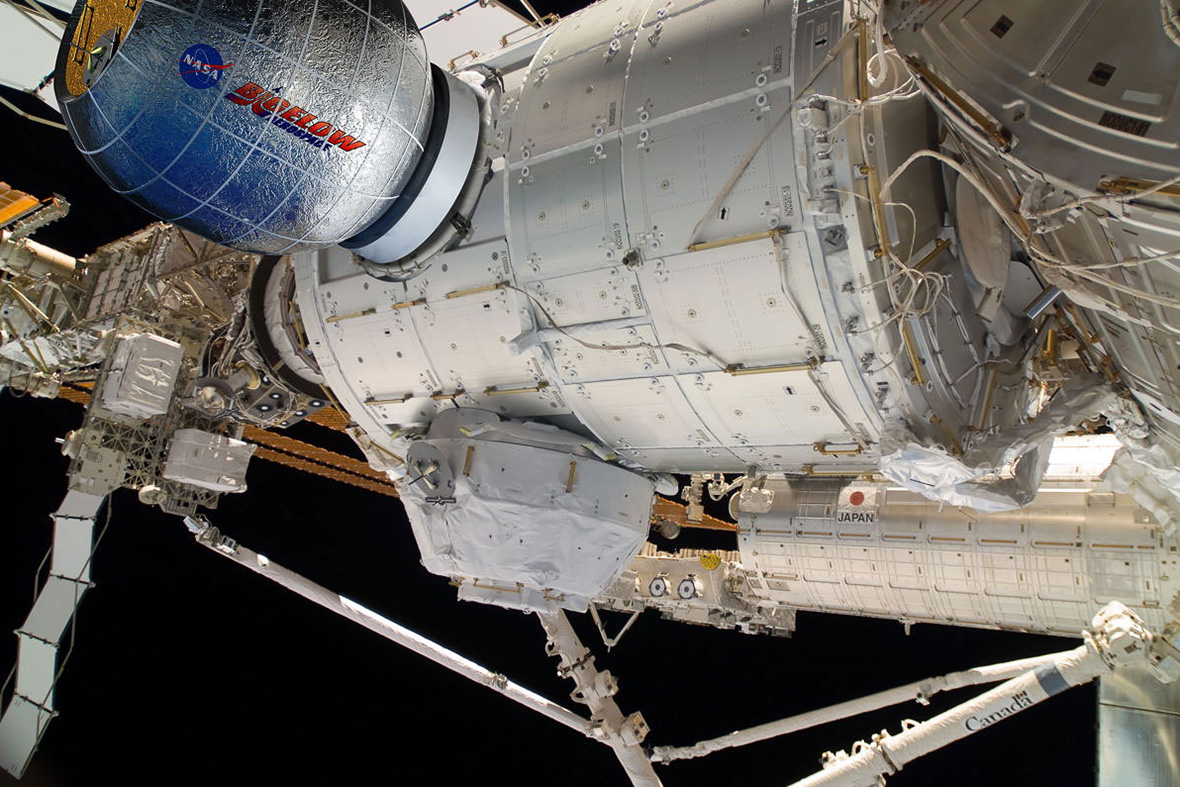

Bigelow Aerospace is expected to begin testing an inflatable space habitat aboard the International Space Station this year. Nasa awarded the company a $17.8m contract to provide a Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM), which is scheduled to be attached to the station for two years.

The BEAM is scheduled to launch aboard the eighth SpaceX cargo resupply mission to the station. Following the arrival of the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft carrying the BEAM to the station, astronauts will use the station's robotic arm to install the module on the aft port of the Tranquility node.

The station crew will then activate a pressurisation system to expand the structure to its full size using air stored within the packed module.

During the two-year test period, station crew members and ground-based engineers will gather performance data on the module, including its structural integrity and leak rate. An assortment of instruments embedded within module also will provide important insights on its response to the space environment. This includes radiation and temperature changes compared with traditional aluminum modules.

Following the test period, the module will be jettisoned from the station, burning up on re-entry.

The company intends to operate free-flying orbital outposts for paying customers, including government agencies, research organisations, businesses and even tourists. That would be followed by a series of bases on the moon beginning around 2025, a project estimated to cost about $12bn.

Other companies could soon be testing rights to own what they bring back from the moon. Moon Express, another aspiring lunar transportation company, and also an XPrize contender, intends to return moon dust or rocks on its third mission.

"The company does not see anything, including the Outer Space Treaty, as being a barrier to our initial operations on the moon," said Moon Express co-founder and president Bob Richards. That includes "the right to bring stuff off the moon and call it ours".

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.