Nasa chief technologist: Mars is first step in humanity's permanent migration into solar system

"Nasa really views our Mars mission as humanity permanently moving out into the solar system – not going to grab a rock, plant a flag and come home. This is to permanently make humanity a multi-planet species."

These words from Nasa's chief technologist Dr David Miller reflect the agency's shift in priorities since the Apollo missions: from that of conquering space, to colonising it. Miller believes that Nasa's current mission to get humans to Mars is only the first step towards a much more important goal of humanity's permanent migration into space.

Speaking to IBTimes UK at the recent Hello Tomorrow conference in Paris, Miller said that humanity's ability to survive indefinitely as a multi-planet species depended on first laying the foundations on Mars.

"There's a lot of potential markets: from travelling out into the solar system as a scientist, or as an entrepreneur, or as an explorer, or just as a tourist for a change of scenery," Miller said. "I think we're just trying to help set the foundation for making this a permanent step in the history of human endeavour."

Pioneering Mars 'should be an international endeavour'

The idea of conquering the Red Planet together, rather than individual countries, has been a popular notion in recent years, as more and more countries and companies combine their knowledge and resources towards joint space exploration.

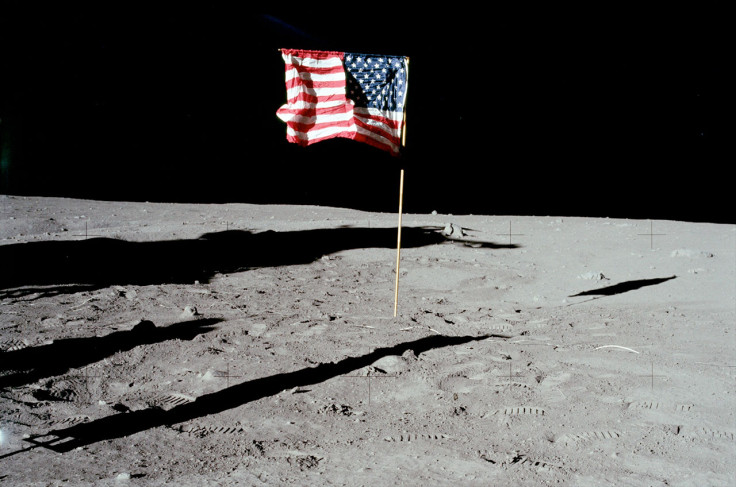

Last month, a Swedish university student designed an "International Flag of Planet Earth" in the hope that it will be adopted by future astronauts, regardless of nationality (see top picture).

"Current expeditions in outer space use different national flags depending on which country is funding the voyage," Oskar Pernefeldt said on the project's website. "The space travellers, however, are more than representatives of their own countries. They are representatives of planet Earth."

This is a sentiment shared by Nasa, which recognises that the driving reasons behind the Apollo missions no longer exist, Miller said.

"There is no more space race," Miller said. "This has to be and it should be an international endeavour, and in fact we're practising that right now on space stations. That's kind of our trial for working away from Earth as an international body."

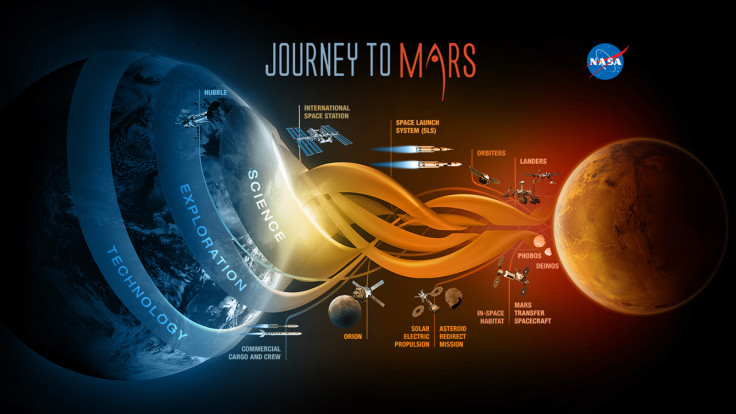

Miller said that beyond international collaboration, Nasa is taking advantage of the commercial sector in order to advance its own space exploration efforts. By doing so, Miller claims that the commercial sector will be pulled out further and further, from where it currently is in low-earth orbit, all the way to Mars.

'You're not going to recognise civilisation again'

Last year, the head of Nasa Charles Bolden outlined three "stepping stones" on the path to Mars, which include testing whether plants can provide reliable food supplies in space, "lassoing" an asteroid into the moon's orbit for tests, and exploring how effectively technologies like 3D printing can be employed for the Mars mission.

Following this plan, Nasa hopes to send humans to an asteroid by 2025 and to Mars in the 2030s. Before humans are sent to Mars, multiple robotic missions will take place to continue laying the foundations for a manned mission already started by the fleet of robotic spacecraft and rovers currently on and around Mars.

For Bolden, the "huge challenge" of getting to Mars and developing planetary independence is paramount for the survival of the human race. By achieving this, however, Miller believes the course of human history and civilisation will be irrevocably changed forever.

"Civilisation has always been challenged by crossing big rivers and traversing mountain ranges and sailing vast oceans, but every time we do it, in the long run the growth of civilisation has been positive," Miller said.

"Once we get over this big challenge of permanently getting out into the solar system, I think you're not going to recognise civilisation again. It's going to be a huge boost for civilisation. The question is when."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.