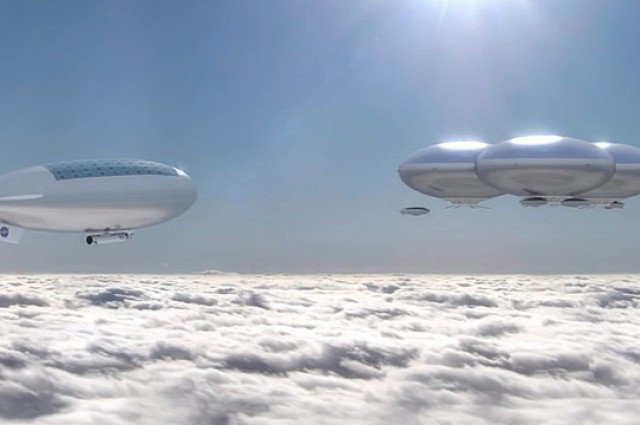

Nasa plans floating cloud cities on Venus to study planet

Venus could be one hell of a planet to land on, but scientists believe that mankind can inhabit floating cloud cities in its atmosphere.

Nasa's Langley Research Center has visualised exactly this in the High Altitude Venus Operational Concept (Havoc).

Dale Arney and Chris Jones from the Space Mission Analysis Branch contend that these cloud cities make Venus a better prospect than Mars for space-faring humans.

The surface of Venus is hellish, with 92 atmospheres of pressure and temperatures of nearly 500 °C. Not to forget the sulphuric acid rain. The planet also generates its own lightning.

But the atmosphere at 50kms is relatively much more hospitable, the team says.

With atmospheric pressure of less than a hundredth of Earth's, and gravity just over a third of Earth's and a temperature around 75 °C, the cloud cities have advantages over habitations on the Red Planet.

The amount of solar power available on Venus could power the floating cities while the atmosphere gives better protection from radiation than on Mars.

Being closer to Earth, and in orbital alignment, a crewed mission to Venus and back would take a total of 440 days using existing or approaching propulsion technology, writes IEEE.

Mars would take much longer with delays caused in waiting for orbital alignment.

Havoc comprises a series of missions that would begin by sending a robot into the atmosphere of Venus to check things out. That would be followed up by a crewed mission in orbit with a stay of 30 days, and then a mission that includes a 30-day atmospheric stay.

The project has been deeply thought out as is evidenced by the description of the vehicle and its journey ending up in the crucial atmospheric entry.

It details the initial moments of entry by the helium-filled, solar-powered airship at 7,200 metres per second till the point where it would start floating at 50kms above the surface.

Besides the European Space Agency's Venus Express orbiter which returned data on lightning on Venus recently, not much has been studied about the planet, unlike Mars.

Havoc is expected to characterise the environment not only for eventual human missions but also to understand the planet and its runaway greenhouse effect.

Meanwhile, the space agency got a boost when the US House of Representatives recently passed its spending of £0.7 trillion and approved £11bn pounds for the next year, surpassing more than its request.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.