Neanderthal DNA gives new timeline for human migration out of Africa

A femur found 80 years ago is shining a new light on Neanderthal evolution.

An ancient human bone discovered decades ago at the heart of a German cave has revealed that more than 220,000 years ago, a human species closely resembling our own left Africa. Its members interbred with Europe's Neanderthals, leaving their mark on Neanderthal DNA.

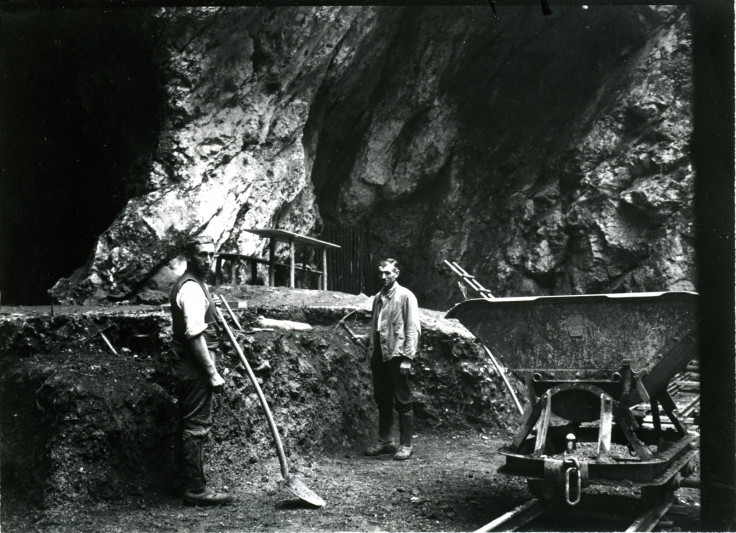

The Hohlenstein–Stadel cave is located in south-west Germany. Eighty years ago, an ancient femur belonging to an archaic human was discovered there. Teeth marks on both sides of the bones suggested that it had been carried in the depths of the cave by a carnivorous animal.

Due to its archaic features, scientists thought that this was the bone of an extinct hominin, but it wasn't until recently, when they succeeded in performing genetic analyses, that they were able to say that this was the bone of a Neanderthal. These findings are now published in the journal Nature Communications.

"People thought it belonged to an archaic group because of its morphology but there was no way to be sure until we performed a genetic analysis. It's only recently that we have developed technologies that allowed the recovery of DNA from the bone," lead study author Cosimo Posth of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany, told IBTimes UK.

"Before that it was impossible, not only because the DNA in the bone is badly preserved due to its age, but because there was a high level of contamination with modern DNA due to many people touching it over the last eighty years."

Neanderthal with modern DNA

The scientists analysed this archaic individual's mitochondrial DNA (see box), which is much more abundant in the bone than nuclear DNA. They wanted to use this genetic data to determine both which group of hominins the specimen belonged to and how old it was (the radiocarbon dating method did not work with such an ancient bone).

The mitochondrial genetic data showed that the specimen belonged to the Neanderthal branch, but to a different mitochondrial lineage than Neanderthals that had previously been analysed.

The researchers estimate that this individual diverged from other known Neanderthals far back in the past, at least 220,000 years ago. The differences between their mitochondrial DNA indicate that there was more mitochondrial genetic diversity in the Neanderthal population than was previously thought.

"We found that this archaic human was a Neanderthal, but that it split from other Neanderthals really early in time, before 220,000 years ago. We identified traces in its DNA of a genetic contribution from a group of hominins that would have closely resembled modern humans," Posth said.

"This is important because it reinforces a model which was proposed recently and according to which the mitochondrial of all Neanderthals comes from a modern human-related population that left Africa in an early wave of migration".

The study thus proposes that there was an intermediate migration out of Africa between 470,000 and 220,000 years ago, before the major dispersion of modern humans out of the continent sometime between 60,000 and 50,000 years ago. A group of hominins that was closely related to modern humans moved from Africa to Europe, introducing their mitochondrial DNA to the Neanderthal population as they interbred.

"We don't know if this group of hominins, which was similar to modern humans, subsisted on its own, but the individuals certainly left their traces in the DNA of Neanderthals, in the same way that many thousand years later, Neanderthals left their mark in us," Posth concluded.

What is mitochondrial DNA and how scientists use it :

Mitochondria are organelles that produce the energy necessary for our cells to function. These mitochondria have their own DNA, which is separate from our nuclear DNA and they are inherited from mother to child. Scientists can us mitochondrial DNA to retrace maternal lineages and population split times.

In fact, changes due to mutations in the mitochondrial DNA over time can be used to distinguish groups and also to estimate the amount of time that has passed since two individuals shared a common ancestor, as these mutations occur at predictable rates.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.