No one knows why ozone layer at lower stratosphere continues to erode despite improvement over the Antarctic

'The reasons for the continued reduction of lower stratospheric ozone are not clear; models do not reproduce these trends,' say researchers.

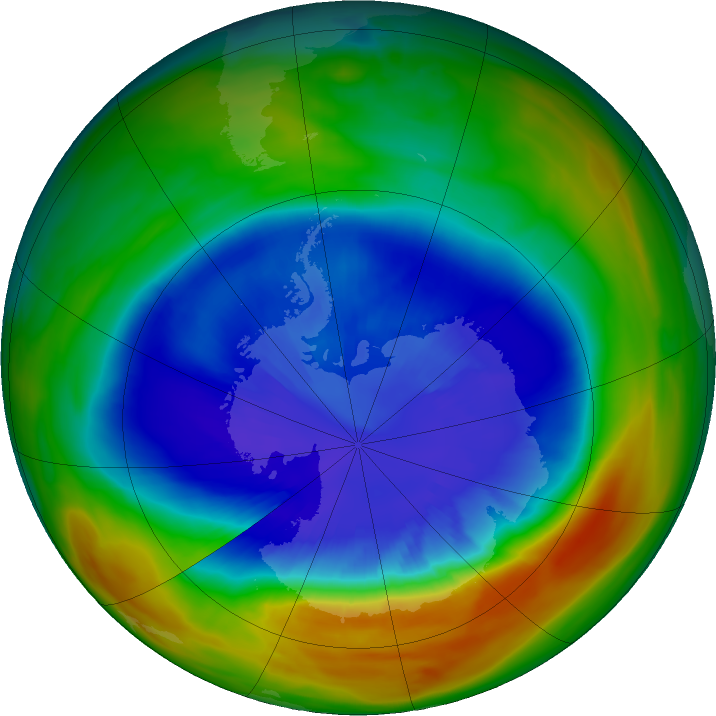

The ozone layer is getting thinner over areas with dense populations. The development is leaving people vulnerable to the harmful effects of ultraviolet (UV) rays as the sun shines brighter over these regions, researchers say.

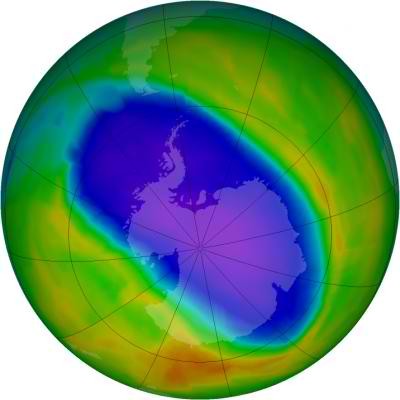

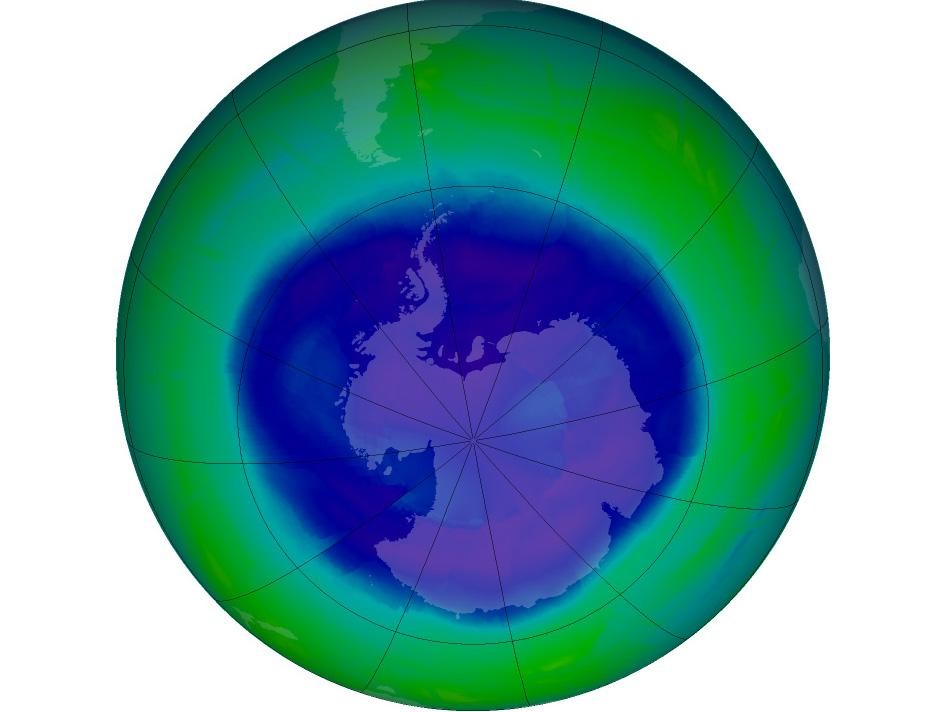

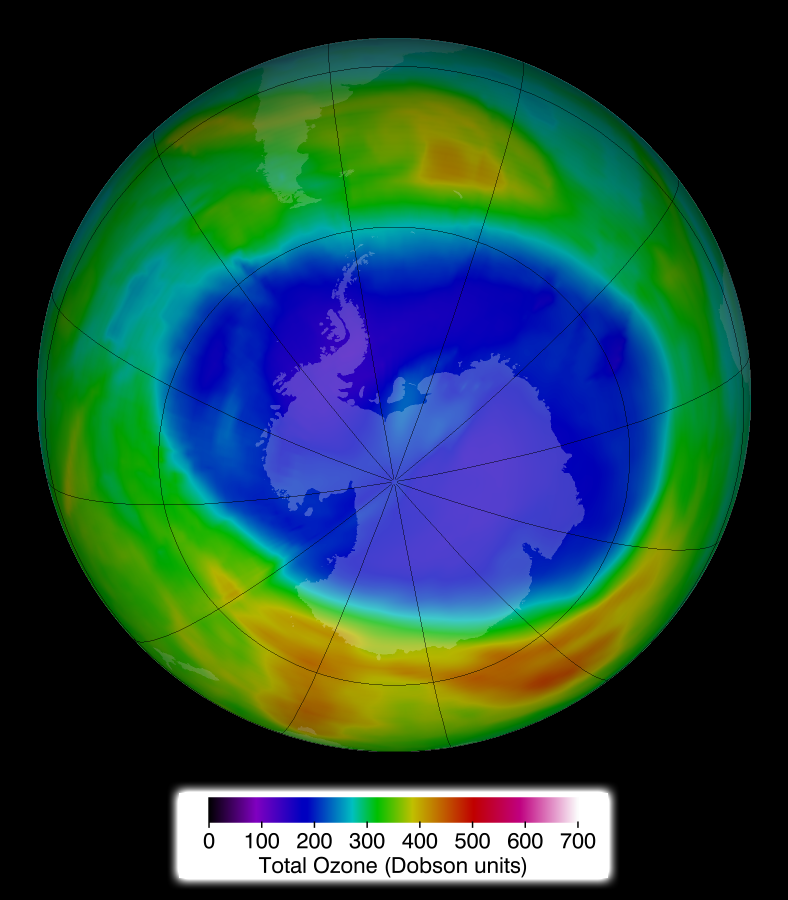

This comes after Nasa announced that the efforts of the Montreal Protocol -- a convention where the world came together to regulate and reduce the use of chemicals that harm the ozone -- had actually worked. The space agency even offered direct proof that the ozone was actually recovering and the large over the Antarctic was healing. The Montreal Protocol was signed in 1987, two years after the hole was discovered.

Now, researchers have found an inexplicable deterioration of the ozone layer in spite of its recovery. In a paper titled "Evidence for a continuous decline in lower stratospheric ozone offsetting ozone layer recovery" published by the European Geosciences Union, scientists have found that "even though upper stratospheric ozone is recovering, the continuing downward trend in the lower stratosphere prevails".

The Stratosphere is the layer of the atmosphere that sits 6 to 31 miles above the troposphere, which is the lowest layer and where weather happens. The lower portion of the stratosphere is where a major chunk of the ozone is and it is here that a good part of the UV absorption happens.

"The study is in lower- to mid-latitudes, where the sunshine is more intense, so that is not a good signal for skin cancer," study co-author and Grantham Institute for Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London co-director Joanna Haigh was quoted as saying by the Guardian. "It is a worry."

Scientists are still unsure why the depletion continues, especially considering the almost outright banning of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in most industrial regions which in turn led to signs of recovery at the lower latitudes in the upper stratosphere.

"Ozone has been seriously declining globally since the 1980s, but while the banning of CFCs is leading to a recovery at the poles, the same does not appear to be true for the lower latitudes," Haigh said in the release. "The potential for harm in lower latitudes may actually be worse than at the poles. The decreases in ozone are less than we saw at the poles before the Montreal Protocol was enacted, but UV radiation is more intense in these regions and more people live there."

However, the very short-lived substances (VSLS) -- ozone-depleting chemicals that have a short life -- are still found in paint thinners and aerosols, and according to the Guardian report, they are not currently banned. "The finding of declining low-latitude ozone is surprising since our current best atmospheric circulation models do not predict this effect," ETH Zurich university professor and study lead author William Ball said in the release. "Very short-lived substances could be the missing factor in these models."

So far, VSLS were not considered to be as dangerous because they were believed to not last long enough to cause any long-term damage to the ozone, but now, further study might be required.

"The reasons for the continued reduction of lower stratospheric ozone are not clear; models do not reproduce these trends, and thus the causes now urgently need to be established," concluded the study's abstract.