Pakistan's political wheel of fortune keeps turning after former PM Imran Khan's arrest

Former Pakistan PM Imran Khan was arrested this week in a corruption case that may have merit. Yet the reason for the move is unlikely to be anti-corruption.

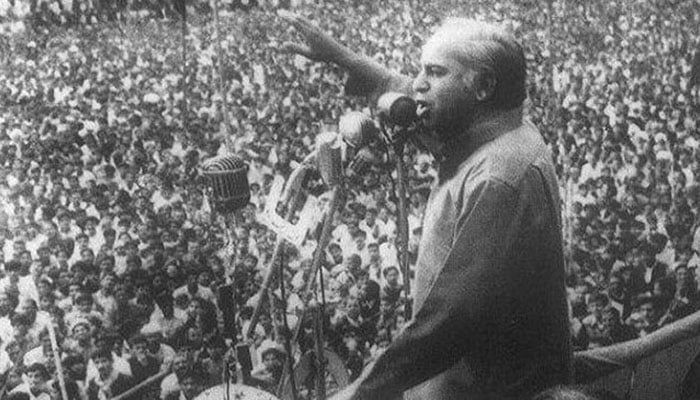

On the 5th of July, 1977, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, with little doubt Pakistan's most popular elected leader to date, was overthrown in a military coup and detained. General Zia ul Haq, the military dictator who took over, released him a month later in the belief that the unrest characterising Bhutto's last few months in office suggested the latter's declining popularity.

What followed shocked Zia - and almost certainly triggered the chain of events that led to Bhutto's hanging. Everywhere the ousted prime minister went, adoring masses followed in unimaginable numbers. He was banned from travelling by train, as the delays caused by the crowds were throwing off train schedules.

This week in Pakistan, another party leader was arrested – on Tuesday, former prime minister Imran Khan was taken away rather unceremoniously by paramilitary personnel – from a court of law, no less.

In response to his arrest, Khan's supporters have flooded the streets. Though crowd numbers are large, what has made them appear greater still is the mass arson that has followed in their wake. Many of Khan's younger supporters have termed the protests "unprecedented". History is perhaps not their strong suit.

Nevertheless, as another elected representative of the people is targeted through the courts in a thinly veiled move many agree has been green-lighted by Pakistan's powerful non-elected institutions, Khan's supporters are unwittingly lamenting the perennial curse of Pakistani democracy: elected representatives finding themselves in legal doldrums as soon as they fall out of favour with the powers that be – mainly the country's mighty military.

At this week's PMQs, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was asked a question about the turmoil in Pakistan following Khan's arrest; an arrest which, in a fresh turn of events, has been overturned by the Supreme Court of Pakistan already.

Sunak replied as any seasoned statesman would. The matter was an internal one for Pakistan. Britain wishes to see a prospering democracy in that country. Britain was following developments closely, but the Prime Minister would refrain from being drawn into commentary or speculation.

So far, so normal.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, the mob went so far as to breach the home of the Lahore Corps Commander – a rare confrontation with the country's military, from a party whose leader was until recently, a favourite of the establishment.

For some, the fact that the party has received no more than a slap on the wrist in the military's official response is proof that it still enjoys some goodwill from that quarter.

Leaked phone recordings – that favourite weapon of the Pakistani establishment – suggest that the raid on the Corp Commander's residence was orchestrated by the senior leadership of Khan's party, the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI).

At the time of writing, many senior PTI leaders have been arrested, the latest being two women in senior positions: Dr Yasmin Rashid and Dr Shireen Mazari. Internet services remain suspended in a move many are decrying as a further black mark on the record of a supposedly democratic government.

More level-headed pundits wondered why the sitting government of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), whose own senior representatives have been victims of similar targeting in the recent, and not-so-recent, past, allowed this politics of revenge to take its course – particularly in such a high-octane fashion.

It does not follow, however, that the case against the former prime minister holds no merit. As ever in Pakistan, many truths cohabit.

The real question in regard to the Pakistani government is how much sway it really holds in the face of the country's powerful non-elected institutions.

Back to Britain, however – which is not as divorced from proceedings in Pakistan as Sunak's words on Wednesday may lead one to believe. The Al-Qadir trust case, for which Khan was arrested, alleges that the former prime minister and his wife, Bushra Khan, received cash and a land grant as a bribe from Pakistani real estate mogul, Malik Riaz.

The allegation hinges on separate proceedings that took place in Britain in August 2019 whereby an investigation by the National Crime Agency (NCA) into the same Malik Riaz resulted in the repatriation of £190 million in funds understood to have been embezzled from the Pakistani state.

The NCA investigates money laundering and illicit finances derived from criminal activity in Britain and abroad, and in the case of the latter, returns the stolen money to affected states.

However, what began as a considerable victory for the NCA, which was the largest recovery of assets in its history, has come back to haunt the agency. In an agreement shrouded in secrecy, Shahzad Akbar, an aide to then-prime minister Imran Khan, travelled to Britain and persuaded the NCA not to litigate the matter.

The funds and land at issue in the Al Qadir case were received by then-Prime Minister Khan and his wife just days after the NCA settlement in the UK and the resulting repatriation of funds to the Pakistani state. It is not disputed that the Khan's benefactor, in this case, was Malik Riaz.

At the end of 2019, Khan's aide Shahzad Akbar presented a sealed envelope at a federal cabinet meeting. He said it contained a non-disclosure agreement pertaining to the settlement made between the NCA and Malik Riaz, and that he, Akbar, was seeking cabinet approval of it, without divulging the contents.

This bizarre request was queried by at least one cabinet minister present at the time, then-Minister for Human Rights, Shireen Mazari. The contents of the envelope, however, remained secret.

In subsequent years, one of Pakistan's own anti-corruption agencies, NAB (National Accountability Bureau), attempted to investigate Mr Riaz's dealings in the case.

According to sources familiar with proceedings at the time, NAB approached NCA in Britain through all the appropriate channels to obtain the details of the settlement. After all, the reasoning went, the money was embezzled from the Pakistani people and they deserved answers.

In a curious development, NAB hit a wall. The NCA would not disclose the details of its settlement with Malik Riaz - which brings us back to Khan.

According to those familiar with the NAB investigation, the document in Akbar's mysterious sealed envelope would help to shed light on two central questions of the case:

- How did funds belonging to the Government of Pakistan find their way into Malik Riaz's hands?

- How did Akbar, a representative of then Prime Minister Imran Khan, manage to present such a compelling argument to the NCA, an independent British agency, that the latter refuses, to this day, to reveal the details of the case to investigating agencies of the Pakistani state?

This newspaper's sources further predicted that without answers to the questions above, the NAB or any other investigating agency in Pakistan, for that matter, will find it very hard to prosecute Khan in the Al-Qadir case.

Ultimately, in their haste to dispense with Khan – rather conveniently a mere few months before a general election expected in October this year – the powers that be, for whom the elected government in Islamabad appears to be little more than a flimsy front, have not considered the matter fully – for they are not in possession of the crucial piece of evidence originating from the NCA's investigation.

As is the lot of many an emboldened political leader in Pakistan, Imran Khan dared to dream that he should have been able to call the shots in his own government independently of the shadowy non-elected institutions that may have helped him on his way to the top job. The belated audacity displayed by the 70-year-old ex-prime minister who has until recently enjoyed the support of the Pakistani establishment was clearly not appreciated by the latter.

There is no doubt, however, that in trying to oppose him, the establishment has reinvigorated his once-flagging popularity.

Pakistan's lot, meanwhile, is such that the epitome of political leadership is still the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto – despite his role in the dismemberment of Pakistan in 1971, despite his problematic economic policy, despite his heavy-handedness with political opponents – the list goes on. It is no wonder then, that although he has been dead for 46 years, Pakistanis of all stripes remember him vividly still.

Bhutto, mounting his own defence at his final appeal, said: "I am entirely at peace with my conscience in this black hole of Kot Lakhpat (jail). I am not afraid of death. You have seen what fires I have passed through."

For all his considerable flaws, many would concede there are none in the current Pakistani political dispensation that can fill Bhutto's shoes. Khan's supporters, on the other hand, ardently believe they have indeed found their messiah – who, in addition to his current troubles, escaped a potential assassination attempt late last year.

Those who don't quite see it that way observe that Khan has already found relief through a Supreme Court Justice known to be sympathetic to the PTI. Further, the party's senior leadership is moving to disavow the violence of its supporters – lest they alienate their erstwhile military well-wishers past the point of no return.

The only constant seems to be that the cycle of political instability churns on in Pakistan, with political leaders facing the courts whenever they may be getting too big for their boots - whether or not the charges against them are valid is almost peripheral to the matter.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.