The Palestinian Dispossessed: Bearing Witness to the Nakba

Mounir is from the last living generation that experienced the Nakba, the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians from the Holy Land in 1948. This is his story.

Some 18 years after the HMS Endeavour made landfall at Botany Bay in 1770, the British crown colonised Terra Australis under the legal concept of terra nullius – or land belonging to no one. The Latin "nullius" more accurately means "having no legal standing".

The British were of course aware of the existence of the indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, and so the phrase more fully denotes "the absence of 'civilised' people capable of land ownership" according to the Australian Museum in Sydney.

The doctrine was declared null and void by the Australian High Court, some might say quite belatedly, in 1992. Other countries where such notions were to be found in the law, followed suit.

There is a notable exception, however.

In some shape or form, the idea has permeated the consciousness, practice and even law, of the founders of the State of Israel, and their successors.

Golda Meir famously said: "I don't say there are no Palestinians, but I say there is no such thing as a distinct Palestinian people" – also that "there was never a Palestinian nation."

Whilst acknowledging that Palestine was inhabited, Zionism, even at its most benign, insists that those inhabitants do not form a "people".

It is an early embodiment of the dehumanisation of the Palestinian people over the last century that has most recently allowed an Israeli campaign of genocidal proportions to go unchallenged - with more than 10,000, including more than 4,000 children, dead as of today, with no end in sight.

It is no accident that the first country to cut diplomatic ties with Israel is Bolivia, where the majority of the population is either indigenous or of mixed "mestizo" heritage.

Ben Gurion University Professor, Oren Yiftachel, says that in Israel "implementation of the terra nullius approach commenced in 1948 and picked up steam after 1967 – when personal dispossession became collective dispossession, preventing the realisation of Palestinian statehood."

Yiftachel offers, for example, the "legal manipulation" of land in the Negev:

Since the 1970s, Israel has declared lands in the Negev not formally registered at two different points in time – in 1858 and 1921 – as mewat, or 'dead lands'.

He goes on to explain that "these are supposedly uncultivated, unpossessed, abandoned and remote lands, not belonging to anyone, and therefore property of the state. Israel did all this despite the historical Bedouin ownership of the land, most of which was cultivated and settled, according to traditional law, and recognised by the Ottomans and British".

The man I am speaking to today may have something to say about that.

Mounir's Story

Aida is already standing in the open doorway as I reach the top of the staircase to the first floor of her art deco apartment block in North London, tidying up a console table. As she turns around, her face breaks into a wide smile, crinkling her eyes.

I am here to talk to her husband, Mounir. I hear his voice down the hall before he appears himself, moving around with an energy that belies his 82 years.

A Lebanese news channel plays in the background with coverage of the carnage in Gaza. I sense that this has been their constant soundtrack since 7 October.

Aida ushers me into the living room where I sit at the dining table near the balcony. Would I like tea or coffee?

I try to explain that I have just had a cup of coffee but am swiftly made to realise that this is not an acceptable response.

Let's start from the beginning, I tell Mounir as he joins me and my coffee (and biscuits of course) at the dining table.

"I was born in Haifa in Palestine in 1941."

Mounir is a Palestinian Christian – part of a dwindling generation of Palestinians who have experienced firsthand the dispossession of their land and everything that came after - who have memories of a childhood in a place called Palestine prior to 1948.

I am here today to bear witness to his story.

Mounir continues, "We were lower middle class. My father, Morice, worked as a railway mechanic in the Palestinian Railway - that used to go from Palestine via Lebanon to join the Hejaz line - the one that was bombed by Lawrence of Arabia."

The Arabs bombed the railway as part of their resistance against the Ottomans - a resistance supported by the British for their own aims – T. E. Lawrence being one guise of that support.

Mounir talks to me of the callous way in which the Allies cleaved the former Ottoman empire into various fragments, based on contradictory, oftentimes secret agreements.

Whilst the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement drew up spheres of influence between Britain, France and other allies for the Ottoman Empire to be carved up under a mandate system, Britain's allies were not made aware of ongoing discussions that culminated in the Balfour Declaration of 1917 in which the British lent support to a homeland in Palestine for the Jewish people – neither was Hussein, ruler of the Hejaz, who was in separate negotiations with the British, made aware of such an offer to the Zionist movement.

Hussein was given to understand that the British would support a united Arab state up to the Mediterranean excluding some territories further north in what is now Lebanon and Syria, in correspondence that is now the subject of considerable controversy.

The secret Sykes-Picot agreement carving up the Ottoman Empire caused a prodigious scandal for the British when Lenin exposed it following the Russian Revolution.

Seeking Safety

"We were a family of 5," Mounir said, explaining he had a brother and a sister.

"Trouble (was instigated) by certain Zionist gangs in Palestine, which was at the time, under the British mandate. (We) witnessed massacres perpetrated by the Haganah and Lohamei Herut Israel Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) gangs; and the Stern gang – headed by Menachem Begin, who later became prime minister of Israel."

Mounir then recalls, "(Begin) was wanted at the time as a terrorist by the British for his involvement in the bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, which was the headquarters of the British Mandate Authority."

The reference is to the July 1946 bombing of the hotel, in which 91 people were killed. It was carried out by the Zionist paramilitary organisation Irgun, at the time headed by Begin – on the orders of the Haganah.

The bombing was a response to British action against the Jewish insurgency in Palestine between 1944 and 1948. It has been called "one of the most lethal terrorist attacks of the twentieth century" by American security analyst Bruce Hoffman.

Nevertheless, the bombing did not shake the resolve of the cross-Atlantic alliance in "having regard to the sufferings of the innocent Jewish victims of Nazism", with Attlee emphasising to Truman that it "should not deter us from... bring(ing) peace to Palestine," by which he meant the Jewish nation in Palestine.

It is a stark contrast to the lack of empathy extended to the indigenous Palestinians then or now, despite the 76 years of dispossession they have suffered.

Indeed, Menachem Begin said in 1982: "The Palestinians are beasts walking on two legs." No wonder then that the IDF chief is employing language such as "human animals" these days.

Mounir recounts that his family "could not take the horrors anymore, witnessing the massacres" of fellow Palestinians and that they were "scared for their children".

He says: "Like many others, we were victims of ethnic cleansing."

The young family ended up in Beirut in Lebanon, 90 miles from Haifa, in March 1948, just before the declaration of the State of Israel in May.

"We came on the back of an open truck, which was driven by a relative of mine. Many others fled from the sea from Acre, south to Egypt, and some to Syria and Jordan," Mounir recalls.

Mounir's family expected a temporary relocation, not the permanent catastrophic expulsion that is today called the Nakba in Arabic.

"We moved into a makeshift house. We came with basic items, expecting to go back. All my father's property was in Haifa – and they took it over," he says, referring to Zionist gangs.

"My uncle, who was a young, single man at the time, opted to stay (in Haifa). From him, we know that the property was housing new immigrants – from Eastern Europe."

Since Mounir was so young when he left Haifa, his memories are blurry. He said: "I have a little memory of our house and the side street it was on. The neighbouring house was shared by my uncles. My parents were renting out a room to a Jewish lady.

"Before the Zionists dispossessed us, we were living together harmoniously - Muslims, Jews, Christians, Druze."

Amongst Mounir's memories are also less pleasant reflections of a childhood marred by increasing violence.

"I could not attend school because of sporadic strikes, demonstrations and Zionist attacks. I remember that my cousins lived nearby and whenever it was safe, we would go out on the pavement to play together."

"One Month's Stay"

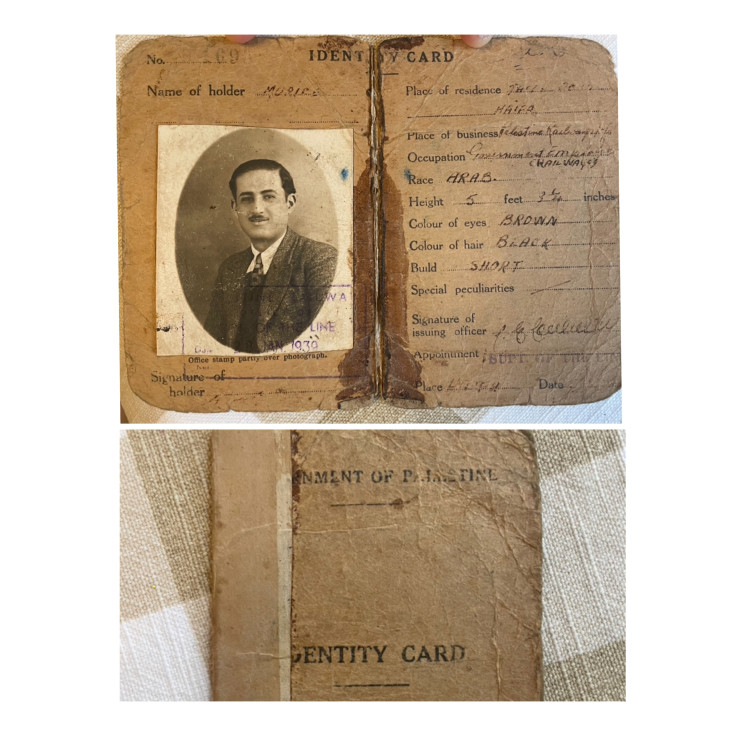

Mounir showed me his father's British mandate-era passport.

He points to the word at the bottom: "Palestine."

"It embossed!" he emphasises.

Leafing through the worn pages, Mounir said, "Let me show you the date when we crossed over into Lebanon - and that was the last time we ever set foot in Palestine."

He points to a stamp filled out in a mix of French and Arabic.

16 April 1948 is the date of entry.

"Sejour au Liban limité" - i.e. stay in Lebanon limited to: "Shahr Wahid" - the latter is arabic for "one month".

"One month's stay! It is now 76 years and counting," Mounir says.

Mounir's life in Beirut was again beset by challenges - this time the hardships of refugee status, following the pain of dispossession. He recalls being enrolled in a "very rudimentary" school for refugees that he and his brother walked to - and not being "appropriately dressed... for the extreme cold".

Mounir earned a Business degree at the American University of Beirut and then studied Law. However, there were restrictions on refugees' ability to work.

"As refugees, we only had a document called "Laissez Passer" that bestowed a right of residency on the holder, but not the right to work.

"Unofficially, you could find menial work. My father was a construction crane operator. We were very poor. We were surviving on UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency) rations," he recalled, observing that there are still countless refugee camps in Lebanon today.

Mounir, however, had better luck than his father.

Employers could apply for work permits for refugees if they so desired. Still, as Mounir noted, these permits did not come with social security.

"I managed to find work with an auditing and accounting firm owned by Palestinian businessmen. As part of my job, I travelled to Saudi Arabia, Libya and other parts of the Arab world."

By this time, Mounir was married. His wife, Aida, is also of Palestinian Christian descent. Younger than Mounir, she was born to Palestinian refugees in Beirut.

As for many Palestinian refugees in the region, more upheaval was on the way.

Civil war broke out in Lebanon in 1975. The largely sectarian conflict featured a dizzying array of warring factions, backed by various foreign sympathisers.

The Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) became a party to this bloodshed. After a massacre of Palestinians at Karantina, the PLO perpetrated tit-for-tat bloodshed at Damour.

Invading Lebanon in 1982, the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) became a significant party to the conflict - unfortunately, another theme in this region.

With an eerie sense of déjà vu, Mounir recalled: "There was a lot of bloodshed; killing at Dbayeh and Damour (1976), that preceded the more well-known massacres at Sabra and Shatila (Palestinian refugee camps)."

Israel's infamous role in facilitating the massacre of Palestinian refugees by the Lebanese Christian Phalangist militia at Sabra and Shatila in September 1982 is the subject of two subsequent inquiries, domestic and international.

Both hold Israel responsible. The independent commission led by Seán MacBride found Israel to be responsible for the actions of the Lebanese militiamen and thus complicit in genocide. The death toll was estimated at 2,000-3,500.

Israeli Deputy Prime Minister David Levy later commented: "I know what the meaning of revenge is for (the Phalangists), what kind of slaughter... Therefore, I think that we are liable here to get into a situation in which we will be blamed, and our explanations will not stand up."

Mounir recalled: "At that time, I opted to leave for Greece. In Greece, in 1978, I started a family. I had one girl and two boys – I lived in Greece for over twenty-five years and was granted Greek nationality."

He has wonderful memories of Greece, saying that he found Greek society very generous and sympathetic – a fitting reflection of the Greek state's long-standing enthusiastic support for an "independent Palestinian state".

Mounir rails against "the Zionist myth was that this was just an empty land".

There is convincing evidence against the notion that the early Zionists claimed the land was truly empty. However, the dehumanising "terra nullius" approach is hardly any better – having at its heart the belief that those who already lived on the land were not worthy of it.

We see it in popular culture. A 2004 episode of the popular US sitcom The West Wing, is an example of this disregard.

In the episode, Chairman US Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Fitzwallace (cast as a black man, for good measure), stands on the Gaza border and addresses the displacement of the Palestinians by saying: "You know, after fifty years, one option might be to get over it."

One may be forgiven for asking if the scriptwriters of an otherwise very liberal show engaged in denial of the Nakba with those lines.

As Mounir said: "There were people. There were people there with a civilisation, agriculture, minor industry, peaceful villages – but the Zionist movement destroyed all that peaceful coexistence."

David Ben-Gurion displayed more self-awareness – though not much more sense of justice – when he said: "[Palestinians] see but one thing: We have come and we have stolen their country. Why would they accept that?"

Yet to look at the news coverage today, it seems this basic fact of history is knowingly ignored.

As the death toll in Gaza climbs, this dehumanisation is itself a weapon of war. No amount of civilian casualties, thousands of dead children amongst them, seems to warrant the world saying: "Enough."

Neither do calls by sitting Knesset members to "flatten it like Dresden" or to perpetrate a "second Nakba" seem to awaken the conscience of those in the halls of power.

I ask him, finally, about the right of return. Does he want to go home?

"It is my only wish before I die. I still have the address of my house there. My cousins still live in Haifa. I don't even want compensation for my seized property – I just want the right to return."

Does he think Palestine will become a free, sovereign country?

"I have no doubt that justice will prevail. It will take time. Probably not in my lifetime; but it will be returned to us. This struggle – it's not a piece of property we're fighting for. It's morality and justice."

As I collect my things and prepare to go, I spot some cushions on an armchair. I recognise the Palestinian Tatreez embroidery on them. In the centre is a highly stylised Arabic word I cannot quite make out.

"What does it say?" I ask Aida.

There's a passing look of incredulity when she turns towards me. "Al-Quds."

Silence.

"Jerusalem!"

To paraphrase Blake amidst the current reality where the UK government is mulling the possibility of banning the waving of the Palestinian flag, perhaps we should say:

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my standard sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In that ancient Holy Land.

For what is the alternative? That a hundred years from now, there will be no more Palestinian people in the land from the river to the sea?

That our grandchildren will stand in a museum in some delightfully "neutral" European locale such as Amsterdam right next to the Anne Frank Museum – tutting at that awful genocide that their forbears let slip by? Except, "slip by" will be a difficult label to slap on to the world's first live-streamed ethnic cleansing.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.