Rare and tiny pterosaur discovered from the age of flying giants

Discovery alters traditional view that skies of Late Cretaceous period were dominated only by large beasts.

Between 100 and 66 million years ago – otherwise known as the Late Cretaceous period – flying reptiles, called pterosaurs, roamed the skies of ancient Earth. These animals were the earliest known vertebrates to have evolved powered flight and most were large – some were comparable in size to a giraffe and had wingspans bigger than a small plane.

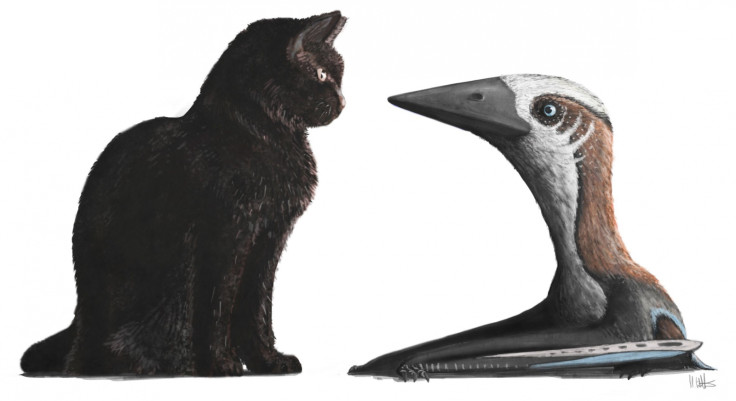

However, a new pterosaur specimen has been discovered in British Columbia, on the west coast of North America that defies the norm. The 77 million year-old fossil is a rare small-bodied pterosaur with a wingspan of only 1.5 metres, unusual given that most pterosaurs had wingspans of between four and five metres. The finding has been reported in the journal Open Science.

The fossils have been identified as those of an azhdarchoid pterosaur, a group of short-winged and toothless flying reptiles which dominated the last phase of pterosaur evolution in the Late Cretaceous. Previous studies of this period suggest a time where the skies were home only to large pterosaur species, as well as birds. However, the new finding challenges that view and provides important information about the diversity and success of pterosaurs at this time.

"This new pterosaur is exciting because it suggests that small pterosaurs were present all the way until the end of the Cretaceous, and weren't outcompeted by birds", said Elizabeth Martin-Silverstone, the lead author of the study, and a palaeobiology PhD student at the University of Southampton. "The hollow bones of pterosaurs are notoriously poorly preserved, and larger animals seem to be preferentially preserved in similarly aged Late Cretaceous ecosystems of North America. This suggests that a small pterosaur would very rarely be preserved, but not necessarily that they didn't exist."

Dr. Mark Witton, a pterosaur expert at the University of Portsmouth, analysed the fossil in collaboration with Martin-Silverstone. "The specimen is far from the prettiest or most complete pterosaur fossil you'll ever see, but it's still an exciting and significant find," he said.

"It's rare to find pterosaur fossils at all because their skeletons were lightweight and easily damaged once they died, and the small ones are the rarest of all. But luck was on our side and several bones of this animal survived the preservation process. Happily, enough of the specimen was recovered to determine the approximate age of the pterosaur at the time of its death. By examining its internal bone structure and the fusion of its vertebrae we could see that, despite its small size, the animal was almost fully grown. The specimen thus seems to be a genuinely small species, and not just a baby or juvenile of a larger pterosaur type."

The absence of small juveniles of large pterosaur species – which must have existed - in the fossil record suggest that there is a preservation bias against small pterosaurs from the Late Cretaceous. According to Martin-Silverstone this adds to a growing body of evidence that "the Late Cretaceous period was not dominated by large or giant species, and that smaller pterosaurs may have been well represented in this time."

"As with other evidence of smaller pterosaurs, the fossil specimen is fragmentary and poorly preserved", she said. "Researchers should check collections more carefully for misidentified or ignored pterosaur material, which may enhance our picture of pterosaur diversity and disparity at this time."

The new finding comes as scientists announced the discovery of a superbly preserved fossil in the Patagonia region of South America which belongs to an entirely new species of pterosaur from the Early Jurassic period – spanning the period between 200 and 175 million years ago. The new species has been named 'Allkauren koi' from the native Tehuelche words for brain – 'all' – and ancient – 'karuen'.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.