Refugee crisis: Pakistani migrants in Greece 'treated like animals'

"I didn't come here for money, I had money in my country, I was a farmer with land and animals. But now my brother is dead, I am the only son left in my family," Gulfam Hassan, 33, is a refugee fleeing political violence in Pakistan.

As a campaigner for the PTI, the Pakistani political party led by former cricketer–turned–politician, Imran Khan, Gulfam became the target of extreme violence – he claims to have been tortured to the extent that he required plastic surgery.

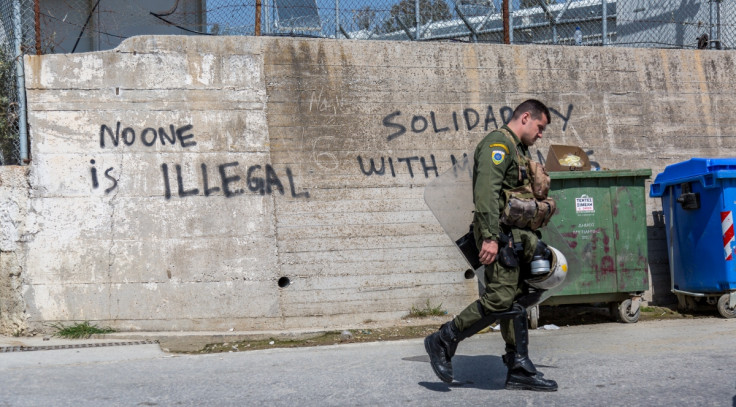

But now detained against his will in the Moria refugee detention camp, on the Greek island of Lesbos, Gulfam finds himself once again involved in life-or-death political action, as the leader of a hunger strike against conditions inside the camp.

Pakistanis inside the camp have held daily protests against what they claim is a deliberate attempt to single them out for deportation. Some 156 Pakistanis have been on hunger strike since last week. Gulfam claims that Pakistanis are being confined in a high-security detention facility inside the camp called "Section B" and that they are not are not being given proper access to claim asylum.

"Greek officials are breaking the laws and don't give us our rights," he told IBTimes UK over the telephone. "Everybody here wants asylum,but the police arrest us and send us to detention. They want to deport us to Turkey.

"Only Pakistani and Bangladeshi people are being targeted. I think Greek officials hate us. They are treating Pakistani people like animals."

Gulfam's brother was killed and he was wounded in a polling station shooting. As the sole remaining son, his parents convinced him to travel to Europe to seek safety. He worries about the safety of his family, particularly that of his father who suffers from a kidney disease.

Asylum services overwhelmed

Amnesty International, which has managed to obtain access to the restricted site, describes conditions in the camp as "appalling" and warns that "automatic, group-based detention is by definition arbitrary and therefore unlawful.

"People detained on Lesbos [...] have virtually no access to legal aid, limited access to services and support and hardly any information about their current status or possible fate. The fear and desperation are palpable."

The latest agreement between the EU and Turkey, which came into force on 20 March, means that all refugees arriving on Greek shores will be detained until their asylum claims are processed. Those whose claims are rejected will be returned to Turkey. The detentions should apply only to those who arrived after 20 March.

However, understaffing and continued arrivals have overwhelmed authorities on Lesbos. As a result, many who arrived before the date are also being swept up and detained. Shamshaid Jutt, a 21-year-old computer science student from Sialkot, Pakistan, has an arrival slip which proves he landed on Lesbos on 28 February – almost three weeks before the new deal. But due to the backlog he was not registered until 22 March – two days too late. He has now been detained inside Moria.

"There are only two officers inside taking interviews," he says, "and they are taking interviews on Skype and sometimes the internet doesn't work. There are thousands of refugees and it's a problem because they only interview 15-20 refugees per day. The process is very slow."

Shamshaid believes that Pakistanis are being overlooked because of a belief that Pakistan is a safe country. "I asked why Pakistanis cannot register for asylum and the reply was that because Pakistan is not involved in an official war," he says. "Yes, Pakistan is not involved in an official war, but inside there are many wars in other shapes – shootings, terrorists, Taliban, mafia, gangs, kidnapping and poverty."

Shamshaid fled Pakistan for those very reasons. His family are the target of criminal groups, known in Pakistan as ishtiari gangs. His father was shot by members of the gang during a robbery, leaving him permanently disabled, while his brother, Ajaz Ali, was gunned down and killed by the gang as he waited at a bus stop.

After the arrest of the murderers, the gang threatened to kill all the remaining children in the family if Shamshaid's father refused to pardon the killers, legally absolving them of the murder.

"They said if you don't forgive us we'll continue to target your family," he says, "even your children when they go to school, we will target them and kidnap them. So, as my parents care about me and I am the only person in my family who has got an education, they sent me to Europe to be safe."

But his journey through Iran and Turkey was far from safe. He was kidnapped and held to ransom while travelling through Iran. His surviving brother, Arfan Shahbaz, transferred $700 (£491) to the kidnappers to secure his release, but not before Shamshaid was beaten and left with scars on his arms and shoulders.

"After I was released I travelled to Turkey over the mountains by foot. I think I crossed 10 or 12 mountains. The mountains are very high there, it was very dangerous. Sometimes I crossed ice rivers up to my chest."

"I want to go to Finland to finish my studies. My family already sold everything we own so I don't have the money to pay for university, but I was told there are no tuition fees in Finland."

But before he can reach Finland, Shamshaid must first get out of Moria. "I'm scared because I don't know what will happen tomorrow or next week," he says. "I am scared that any time the police will put me in the detention area and will send me to Turkey."

'Anxiety and confusion are widespread'

The EU has come in for heavy criticism from the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR) and aid-groups for sending migrants and refugees back to Turkey, which many have described as being an unsafe destination where proper access to asylum cannot be guaranteed.

According to 26-year-old Kaleem Akmal from Sahiwal, Pakistanis fear for their safety in Turkey. "They are scared about kidnappers in Turkey who pose as taxi drivers," he says. "They say they will give you a lift, free of charge, but then kidnap you and beat you. They demand money, they take your phone and your things."

Kaleem left Pakistan due to poverty and an inability to find work as an electrician. He spent $4,500 (£3,600) on his journey to Europe and now fears being deported to Pakistan even poorer than before he left.

According to Boris Cherishkov, spokesperson for the UNHCR on Lesbos, anxiety in the camp is leading to desperation amongst the inhabitants. "Anxiety and confusion are widespread among the population because of overcrowding and food shortages," he tells IBTimes UK. "We have seen bouts of violence among individuals and sometimes groups.

In response to the allegations, Lieutenant-General Tsirigoti of the Hellenic Police denied that anyone in Moria was being denied access to asylum and stated by email that "registration and identification by the police is taking place for all those who enter our country illegally, including economic immigrants [such] as Pakistanis" and that all refugees inside Moria are "are thoroughly informed of their rights and obligations in their own native language".

Will Horner is a freelance journalist based in Athens covering the refugee crisis and Greek politics. A masters graduate in European Politics, his work has been featured in the Independent and Middle East Eye. His Twitter handle is @willhorner.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.