Right to be Forgotten - Google rejects 70% of 250,000 removal requests

On 13 May 2014, the Court of Justice of the European Union made a historic judgement in favour of Spanish man Mario Costeja González who had claimed that an auction notice about his repossessed house in Catalonia dating from 1998 should no longer appear when someone typed his name into Google.

The court agreed with González and said that "inadequate, irrelevant or no longer relevant data" should not appear in results returned from search engines like Google or Bing. Despite the borderless nature of the internet, the ruling only applied to search carried out within Europe on local versions of the search engines.

The ruling was widely criticised at the time, with Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales calling it "ridiculous".

One year on from the ruling, it remains unclear just whether the decision was a positive move by the European court, but what we can see is just how many people have sought the right to be forgotten (and why), what percentage of these have been successful (and why), and what impact if any the ruling has had on websites around the world.

Google refused 70% of 250,000 requests

Just two weeks after the court's ruling, on 29 May, Google published an online form which allowed those seeking "to be forgotten" to request the removal of a link from search results.

According to Google's latest Transparency Report, the search giant has received 253,617 requests, dropping from a high of around 1,500 per day in the first three months to the current level of about 500 per day.

Google, which said initially that it had been "disappointed" with the decision, has had to put a lot of resources into dealing with these requests. Initially it was taking an average of 56 days to process each request. That wait time is now just 16 days.

These statistics come from identity management company Reputation VIP, which launched the website Forget.me in June 2014 to allow people "to exercise their right to be forgotten efficiently and easily".

So far the company has sent 61,753 URLs to Google giving them a significant set of data about how Google handles these requests, the rate of refusal and the reason why an application is not successful.

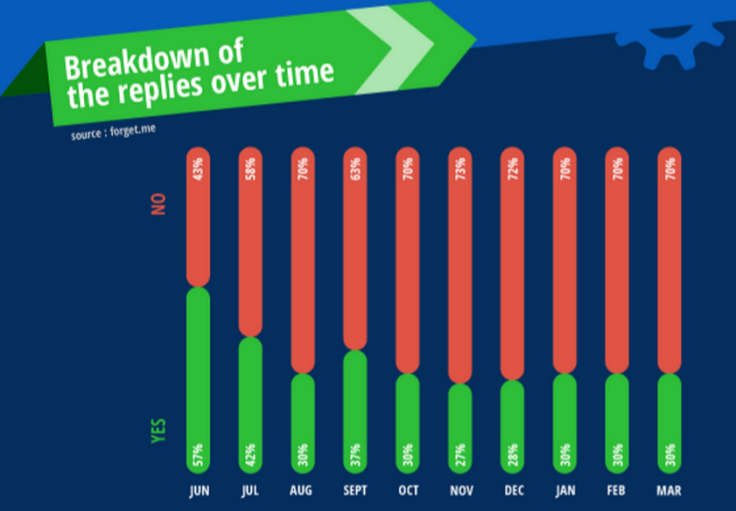

While Google's official transparency report says that it has removed 41.3% of the URLs it has evaluated (it says it has evaluated a total of 920,258 URLs for the 253,617 requests it has received), Forget.me says that the refusal rate based on individual requests has now stabilised at 70%.

Initially Google was refusing just 43% of requests though this was likely down to the fact that Google – along with just about everyone else – was unclear about just how to implement the ruling.

Invasion of privacy

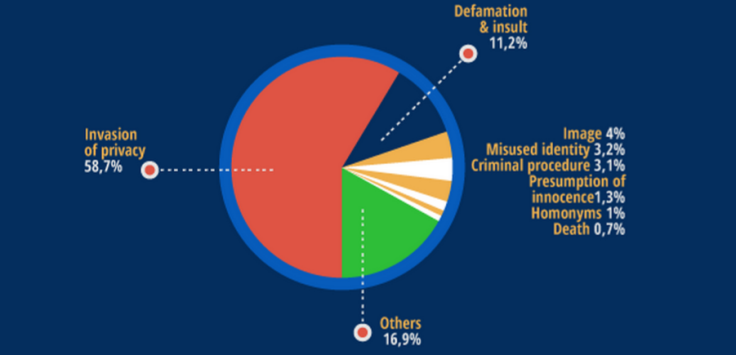

The reasons for an individual seeking to have a link removed are numerous and include legal proceedings, violation of the presumption of innocence, homonyms, damage to reputation or image, and identity theft, but by far the biggest reason for seeking the removal of a link is invasion of privacy, accounting for almost 60% of all applications.

When refusing an application, Google gives applicants a reason why the request has been denied, and here Google seems to be particularly reticent when a URL is related to a person's professional activity with 26% of all refusals saying it "concerns your professional activity".

The other main reasons for refusal are that the link is "in the public's interest" and that "you are at the origin of this content".

This aspect of the Right to be Forgotten ruling is one of the most contentious. Google is a private company yet is in the strange position of having to be the "arbiter of history", as Jimmy Wales told IBTimes UK last year.

Wales was part of an advisory council set up by Google in the wake of the ruling to try and get to grips with what it meant, and speaking about this aspect of the ruling in the council's report, Wales said:

I completely oppose the legal situation in which a commercial company is forced to become the judge of our most fundamental rights of expression and privacy, without allowing any appropriate procedure for appeal by publishers whose works are being suppressed. The European Parliament needs to immediately amend the law to provide for appropriate judicial oversight, and with strengthened protections for freedom of expression.

Reputation

Dave King, CEO of reputation management company Digitalis agrees with Wales:

"The guidance by the court was limited in terms of how Google should determine, for example, what constitutes public interest; which is one of the reasons it can cite for not removing links to content. Some might rightly say that's a pretty subjective call for a private company to have to make."

The Advisory Council was set up by Google in the wake of the ruling to "advise [Google] on performing the balancing act between an individual's right to privacy and the public's interest in access to information."

The council held a series of public consultations across Europe before issuing its report in February.

When Google began removing URLs from its results pages in June 2014 there was an outcry from media publications who complained that the process of de-listing articles about certain individuals would adversely affect their business.

Media sites unaffected

That does not appear to have transpired however, with Forget.me reporting that just 3.3% of all URLs that have been requested to be removed coming from press sites, and just 0.4% of these requests being complied with by Google.

Requests to remove links from social media websites accounted for 20% of all applications, with directories (where people's name and address are published online) the next biggest at 14.8%.

As for where the requests are coming from, the UK and Germany lead the way making up over 50% of the total number of requests alone.

Positive or negative?

So, back to the first question we asked, has this been a positive move by the European Union?

It is clear that some, such as Wales, see it as a negative move, but others are not so sure. Bertrand Girin from Reputation VIP says that "one year on, the debate is still far from over".

Girin added that those people whose applications are refused have no way of challenging the ruling, and this needs to be addressed:

"The number of requests regarding privacy is huge, a fact that means simple cases have become more common and that everyone has a right to be forgotten. In view of the number of rejections (70%), it seems right to ask how people who make requests that are dismissed by the search engines can take recourse. It is a subject that deserves the attention of our lawmakers, as part of Europe-wide regulations on the protection of personal data. "

Research carried out by YouGov on behalf of Digitalis says that 92% of people in business Google someone before or after meeting them - and that most are influenced by what they find.

While still having some reservations, King believes that the move has been overall a good one:

"We see the judgement as being a positive result for the man on the street looking to remedy errors of fact or no longer relevant, historic information. In that sense, it's a good thing. But for the high-profile individual or for those with interests in multiple jurisdictions it can enhance rather than mitigate the reputational fallout of historic issues."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.