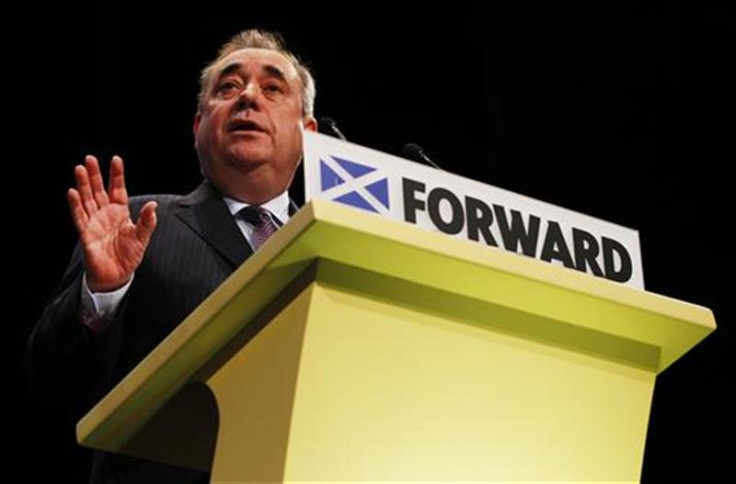

Scottish Independence and Alex Salmond's Currency Dilemma

Alex Salmond, Scottish first minister and leader of the SNP, says Scotland will keep sterling if it gains independence - but there are a number of problems

Amid the glens and the lochs, in the taverns on the streets of Edinburgh, and around the isles broken away from the mainland, hearty debate is taking place about whether or not to break up a union that dates back 300 years.

When once a stone wall was constructed to keep the Scots from going below the border, it is now a fiercely independent nation that is building a political wall to keep the Sassenach away, though only from Holyrood's halls of power.

English tourists and their wallets are still welcome, of course, but should they bring pounds, euros, or some other currency to lavish on their neighbours?

Scotland's government, occupied by the Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) after a barnstorming victory in the 2011 elections, wants full fiscal and political independence from Westminster and to leave the United Kingdom of England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Recent polls suggest as many as 40 percent of Scots support independence, with around 10 percent undecided, as the SNP steps up its campaign to split.

What is as unclear as the outcome of any referendum on independence is how exactly Scotland would manage its currency - or even what currency it would use.

Scottish euros? Alex Salmond backs sterling

At one point it was mooted that a newly independent Scotland could join the eurozone, but this ill-fated single currency area, mired in financial crisis, may have a shorter life left than the UK.

Alex Salmond, leader of the SNP and Scotland's first minister, has pledged to keep the pound and said that an independent Scotland would join the European Union (EU).

However Salmond should not take future EU membership as inevitable and even if Scotland were to join, there are a number of issues arising.

Firstly there would not necessarily be automatic membership granted. All EU member states must agree to a new member joining.

There is no certainty that they will all agree.

As pointed out in a blog by Dr Jo Eric Khushal Murkens, a senior lecturer at the London School of Economics, member states "may oppose independence as secession, and as a dangerous precedent which should not be encouraged in Europe.

"In any event, an independent Scotland would have to join the EU as a new accession state, a process that could take many years," Murkens, who is an expert in Scottish independence, writes.

"Scotland could keep a low profile and go for smooth and rapid acceptance by the EU, or it could enter negotiations in a spirit of confrontation and renegotiate the terms of membership."

Renegotiating a different set of membership terms to those Scotland enjoys as part of the UK could take a long time. Then there are the numerous treaties.

One of the most important, and one the UK managed to secure an opt-out for when it was originally signed, is the Maastricht treaty, which laid the foundations for the euro.

This means Scotland, if it joined the EU, would agree to Maastricht and be expected to join the euro in the future. In fact, as of 2004 EU rules mean new states are legally required to join the euro.

"Both EU membership and the issue of the euro will not be decided by the SNP or by the people of Scotland, but will be regulated (in principle) by the EU Treaties and (on the detail) by the Commission and the other Member States in negotiations with an independent Scotland," Murkens wrote.

Eurozone lessons

Even if Salmond pulls off the diplomatic and legal wrangling to join the EU but keep the pound, he should not ignore the eurozone as there are lessons to be learned.

One of the biggest criticisms levelled at the eurozone is its lack of political and fiscal union between the 17 member states.

Some argue that it is impossible to have a single currency without one central government that holds ultimate power over the economy, with states having local, federalised political power to make their own decisions on social policy.

This ability to make sweeping macroeconomic decisions at times of crisis would help dampen the effect of a meltdown.

What has made the eurozone's response to the current crisis so impotent is its lack of clarity and direction, something that should come with the central government it lacks.

Macro decision-making becomes time consuming and stuttered, punctuated by disagreement between sovereign nations who understandably want to defend their own national interests.

If Scotland were to become independent yet keep the pound, or at the very least keep a new currency pegged to sterling, it would lose that crucial ability to take sovereign monetary action when it is needed.

Without its own central bank to set monetary policy and interest rates, relying still on the Bank of England, Scots would never hold true autonomy from the UK.

"At the moment the SNP leadership seem to be taking a 'don't scare the horses' approach trying to get people to vote for independence on the basis that nothing will change," Patrick Harvie, the Scottish Green Party co-leader and a supporter of independence, recently told the Daily Telegraph.

"This is a strategy for failure. It's about transformational change, not a mini version of the UK state run from Edinburgh instead of London."

Harvie demanded a deadline for transferring to a new and "genuinely independent" currency if Scotland ever gets its independence, though he conceded that there may be a short period of transition where it has the pound.

One of the authors of the SNP's manifesto, Stephen Noon, who is also a post-graduate student in EU law, has set out the case that the Bank of England is as much Scottish property as the rest of the UK nations.

"The UK's central bank is something Scotland and the rest of the UK own together - we must not forget that," Noon wrote in a blogpost.

"This means the rest of the UK does not have exclusive rights to the institution, or an exclusive say on its future.

"Scotland will be entitled to its share of this asset and, as 'part-owner', Scotland will be entitled to representation (something we don't have just now)."

No date has been set on the proposed independence referendum, but it will take place before 2016 when the next round of Scottish elections take place.

Before then the SNP will face difficult questions on the complexity of independence and if it is really possible at all.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.