Spain: Civil war graves exhumed, allowing 90-year-old woman to finally lay her father to rest

A 90-year-old woman will finally be able to give her father – killed in 1939 by General Franco's forces in the aftermath of Spain's Civil War – a proper burial after the mass grave where he was buried was exhumed on request of an Argentine judge.

Historians estimate as many as 500,000 combatants and civilians were killed on the Republican and Nationalist sides in the war. Atrocities were committed on both sides. The victors under Franco executed thousands more after the war, according to British historian Paul Preston's book "The Spanish Holocaust".

Spain passed an amnesty law in 1977 to draw a curtain over the violence. The United Nations and human rights organisations have urged Spain to revoke the law, but Spain has stood by the legal embodiment of the so-called "Pact of Forgetting". Hundreds of Spaniards turned to Argentina for help in uncovering crimes committed during the 1936-1939 civil war and the subsequent 36-year dictatorship, by using international human rights law.

Spanish campaigners have now dug up a mass grave in Guadalajara, after the Argentine court piled pressure on Spain to confront its troubled past. At the request of the Argentine judge, a Guadalajara court authorised the exhumation of the grave, containing 22 bodies of people believed to have been killed by Franco's forces in the months after the end of the civil war. The exhumation is the first agreed to by a Spanish court at the behest of the Argentine investigators.

Wrapped in a fur coat and woollen scarf, 90 year-old Ascencion Mendieta arrived at the cemetery in Guadalajara, north-east of Madrid, to finally see the remains of her father Timoteo, who was shot in 1939 in the months after the Spanish Civil War and buried in a mass grave along with 21 other people. She sobbed as she stood over a deep open grave and murmured "my father" to the unearthed skeleton lying at the bottom.

Mendieta was 13 when her father was executed. "The last memory I have of him was when they took him away to the jail in Sacedon. He was sleeping and they came to take him away, that is the last memory. I never saw him again," Mendieta told Reuters.

She travelled to Buenos Aires in 2013 to give evidence about his death. She was one of hundreds who have used international human rights law to turn to an Argentine court to seek justice for crimes carried out during and after the civil war.

Archaeologists started to dig on 19 January, working from a town hall ledger which meticulously noted in a copperplate hand the names, ages and position of those buried in the town cemetery. Those working on the project believe about 200 bodies in total are buried in pits in this corner of the cemetery, which was sealed off from the rest of the graveyard by a wall until after Franco's death in 1975.

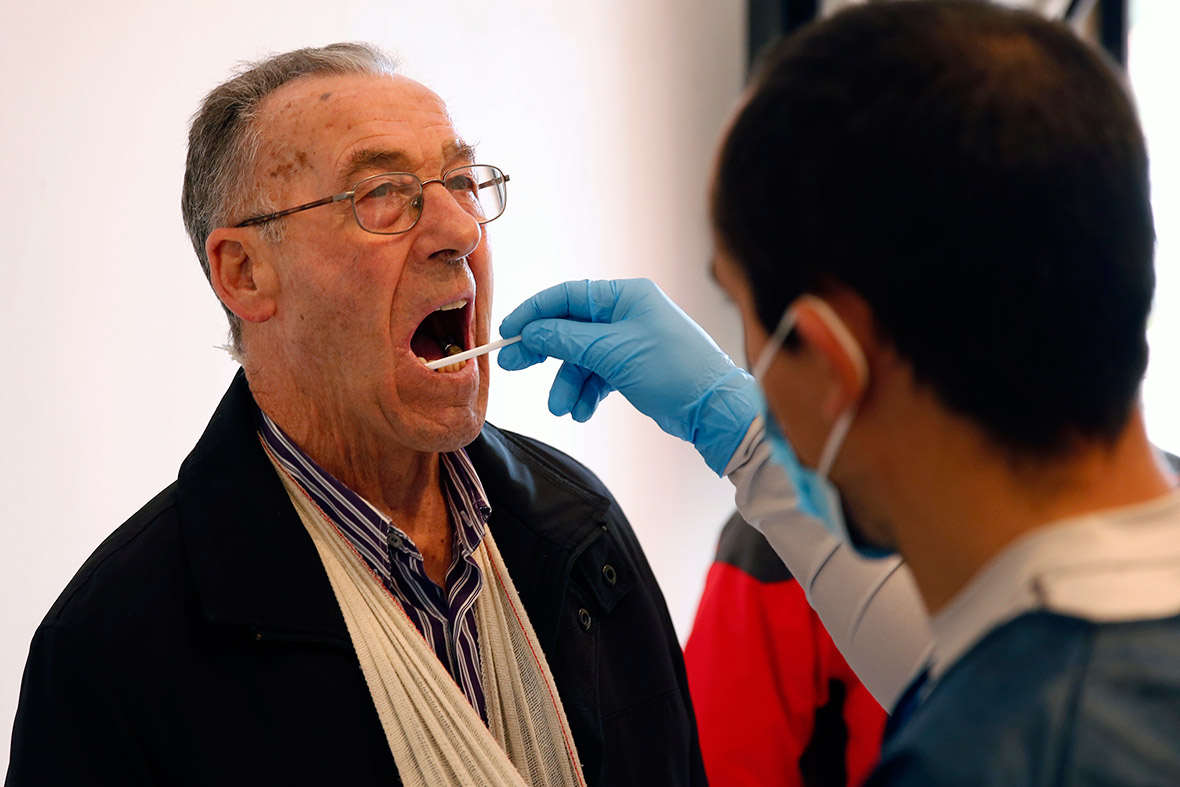

Timoteo Mendieta's body is believed to be the 19th or 20th of the bodies stacked in the grave. As archaeologists worked on digging them up, dozens of families came to the site to find out about relatives they believe to be buried there. Samples from the bones and teeth of the skeletons from the grave in Guadalajara will be sent to Argentina along with saliva swabs from relatives, so identities can be established. Argentina will carry out the tests for free, a service that has not been offered by Spain, Rene Pacheco, the head archaeologist said.

Spain itself used the international law in 2005 to prosecute Argentine naval officer Adolfo Scilingo in a Spanish court for crimes against humanity during that country's "Dirty War". Spain's most famous human rights judge, Baltasar Garzon, played a leading role in the trial, which led to Argentina's 1987 amnesty laws being overturned. Garzon opened an inquiry into Franco-era crimes in 2008 but later dropped the case – an example of the issue's political sensitivity.

Argentine Judge Maria Servini is looking to override the amnesty law to seek justice for Franco-era crimes ranging from torture to shootings in a cross-border lawsuit opened in 2010. Lawyers working on the case with Servini said the case in Guadalajara is the first concrete victory of the Argentine cause and it will likely lead to other graves being exhumed.

"Ascencion Mendieta may have recovered the remains of her father but many other families have turned up wishing to do the same with their loved ones who are in the same grave and other families are looking at the possibility of doing so in the adjacent graves," said Ana Messuti, one of the members of the legal team working on the Argentine cause.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.