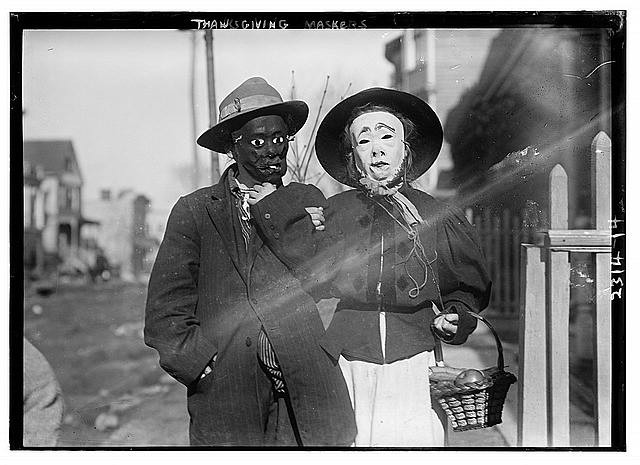

Thanksgiving 2014: The Century-Old Forgotten Tradition of Masking, Cross-Dressing and Ragamuffin Day

Thanksgiving "masking" - dressing up - came from a satire of poverty

Most thanksgiving traditions have stood the test of time. This year, the United States alone will eat 46 million turkeys on Thanksgiving – approximately one for every seven people. Around 46.3 million Americans will travel 50 miles or more from home for the national holiday, and Thanksgiving pumpkin pie is so popular it has spawned poetry.

But a custom dating back more than 100 years ago has long been forgotten – one with a striking resemblance of modern-day Halloween. Thanksgiving "masking" derived from a satire of poverty and the tradition of mumming, an ancient pagan custom in which men and women would swap clothes and visit their neighbours to ask for food or money for Christmas, often in exchange for music.

By the late 19<sup>th century, "masking" had transformed into a day in which children dressed up in costumes, poverty-inspired "ragamuffin" rags and masks, taking to the streets to beg for sweets or money. Thanksgiving soon became known as Ragamuffin Day.

"Thanksgiving masquerading has never been more universal," a report from the New York Times read in 1899. "Fantastically garbed youngsters and their elders were on every corner of the city. Not a few of the maskers and mummers wore disguises that were recognised as typifying a well-known character of myth."

"There were Fausts, Uncle Sams, Harlequins, bandits, sailors. All had a great time. The good-humoured crowd abroad was generous with pennies and nickels, and the candy stores did a land-office business."

Cross-dressing

Dressing in women's clothing was one of the most popular options for boys, in an excuse for mischief on the national holiday. Popular among children and teenagers, the LA Times reported in the early 20<sup>th century that Thanksgiving was "the busiest time of the year for the manufacturers of and dealer in masks."

Unsurprisingly, however, masking, cross-dressing and Ragamuffin Day clashed with the historic and austere traditions of the harvest festival. Frowned upon by society as a distraction from the true meaning of Thanksgiving, some blamed "ill-bred children" for taking part in the celebrations. Others criticised the mocking of the destitute.

"It's difficult to find too much enthusiasm for this unsavoury traditions in newspapers of the day," the Bowery Boys history blog reads.

"Editors preferred to focus on family gatherings, recipes and table placements, not only out of social convention but on the behest of advertisers, who made more money selling turkey and china than cheap masks."

Origins

The exact origins of Thanksgiving masking remain unknown, but reports of "ragamuffin" children begging for sweets began to emerge at the beginning of the 1900s. In November 1909, the New York Tribune dated the phenomenon back to around 1870 in the city. By the 1920s, Thanksgiving masking had morphed into a Halloween celebration.

Although historians have claimed masking was also popular in Chicago and Los Angeles, it is widely accepted that Ragamuffin Day began in New York City.

"This play of masking is deeply rooted in the New York child," a 1909 issue of Appleton's magazine stated. "All toy shops carry a line of hideous and terrifying false faces or 'dough faces' as they are termed on the East Side."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.