UK Government appoints Director for Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom

In recent times free speech has been a controversial topic in Western civil society. This month the government passed new legislation which seeks to protect and promote free speech at British universities.

Freedom of speech is a core value of Western democratic society. In the history of political thought, the philosopher John Stuart Mill has been one major advocate of freedom of speech.

In his famous essay "On Liberty", John Stuart Mill argued: "If all mankind minus one were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

As a key individual right of a civilised society, Mill's philosophy implies that the only grounds on which the right to speak can be impeded are where utterances violate the "harm principle". This means that the individual right to speak should only be deemed illegitimate when it causes direct and serious to others. For example, stirring up an angry mob to behave violently towards others.

However, freedom of speech is a controversial subject across the West today. One example of this controversy is Cathy Newman's interview with Jordan Peterson on Channel 4 News. Jordan Peterson is a Canadian academic and clinical psychologist who became controversial because of his criticism of Bill C-16 which pertains to the expression of gender identity in Canada.

His interview with Cathy Newman caused quite a stir at the time back in January 2018. Whatever your opinion of who is correct in their exchange, it reflects the ongoing controversy of free speech as an issue today.

Accordingly, central to debates on free speech is the question of whether individuals ought to possess the right to offend others in their utterances. In the context of Mill's philosophy, the question is whether the offence caused by an utterance constitutes a serious enough form of harm to justify the constraint of free speech.

On this very subject, when asked why his right to freedom of speech should "trump a trans person's right not to be offended", Peterson argued that "in order to able to think, you have to risk being offensive". Moreover, free exploration and expression of ideas risks causing offence, even if it is not intended to.

Why does the free exploration of ideas matter, you might ask? In the words of British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak: "A free society requires free debate." Moreover, Sunak had previously stated: "A tolerant society is one which allows us to understand those we disagree with." By implication, it is one which allows us to articulate potentially offensive ideas.

Others who have run into controversy over free speech include Elon Musk, who bought Twitter for $44 billion with the intention of upholding free speech. Upon acquiring Twitter, Musk tweeted that "the Bird is freed." However, Musk's management of Twitter has been associated with a rise in antisemitic content.

Musk used his control of Twitter to reinstate the accounts of those who had been previously removed from the platform. This move included Jordan Peterson, alongside others such as Donald Trump and Kanye West. Moreover, another key question is whether we should see social media platforms like Twitter as part of the "public square" where there are limited restrictions on who speaks and what they say.

However, whilst questions around free speech today centre around the use of social media, free speech is no less a controversial issue at the university. In the context of campus life, controversy exists over whether students and student organisations should be able to prevent the platforming of controversial and offensive speakers at university institutions such as student unions and debating societies.

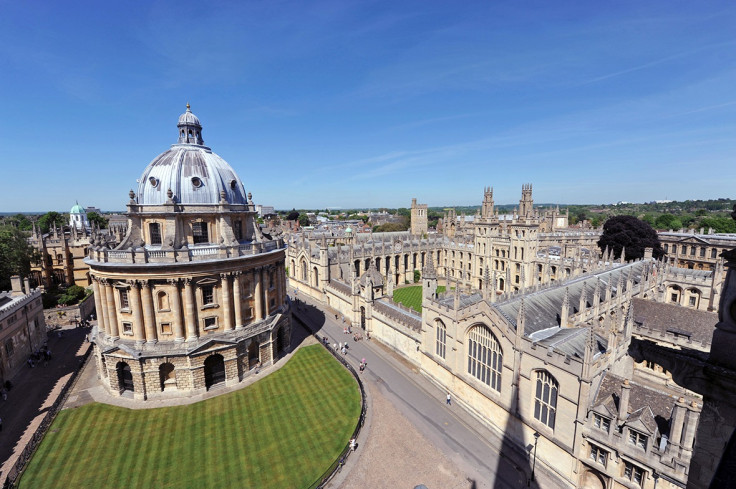

For example, this year, the University of Oxford has been embroiled in controversy over the invitation of Kathleen Stock to speak at the Oxford Union. Kathleen Stock was a professor of philosophy at the University of Sussex until 2021 when she resigned following controversy over her views on gender.

The invitation of Stock to speak at the Oxford Union sparked opposition from the University of Oxford LBGTQ+ Society who called for the invitation to be rescinded. Specifically, they referred to Stock as "transphobic and trans-exclusionary".

However, published in the Telegraph, a Letter signed by over 40 academics (including Professor Richard Dawkins) defended the right of individuals such as Stock to express their views in forums like the Oxford Union. According to the letter, Stock has articulated that "biological sex in humans is real and socially salient, a view which until recently would have been so commonplace as to hardly merit asserting".

This is not the only example of controversy over free speech in university life. Other examples include the pulling of an invitation to former Home Secretary Amber Rudd to speak at the Oxford Union back in 2020. The UNWomen Oxford UK Society had invited Rudd to speak about her role as Minister for Women and Equalities, only for the event to be cancelled just an hour before its scheduled start.

The Freedom of Speech Act

Amidst these free speech controversies, the government have made its position clear. On the 11th of May, the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023 officially became law. The act pertains to "freedom of speech and academic freedom in higher education institutions and in students' unions", with new measures becoming active before the 2024/25 academic year.

English universities, or "registered higher education providers", will be tasked under the law with protecting free speech and academic freedom on campus. The new legislation builds on existing statutory duties which require universities to protect free speech.

For example, the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 articulates the responsibility of universities to uphold free speech in accordance with the law.

There are limits here. According to a blog post by the Department for Education, the act doesn't permit "unlawful speech" which could include "harassing others or inciting violence or terrorism".

Instead, the purpose of the Act is to ensure that university classrooms and campuses are places where students can freely express ideas. Crucially, where certain kinds of course material have the capacity to offend students, the Act is intended to ensure that free and open debate remains the bedrock of university life.

In my experience as a university student, issues such as the history of the British Empire, race, sexuality and gender are areas of discussion where things can get heated in the classroom, potentially leading to students becoming hostile to each other.

In addition to universities, student unions will also be subject and accountable "to the same legal responsibilities" to undertake measures to protect lawful free speech on campus. Failure to undertake these responsibilities could lead to fines for both higher education providers and student unions.

The new 'Director for Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom'

More specifically, following the passing of the new free speech legislation, a new complaints system will be established which is available to "students, staff and visiting speakers" that believe they have been the victim of unreasonable constraints on free speech or academic freedom.

This "free-to-use complaints scheme" will be run by England's higher education regulator, the Office for Students (OfS) and will strengthen the duties of universities and higher education providers to protect free speech.

Undertaking responsibility for investigating reported breaches of the conduct now expected of universities is the newly appointed Director for Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom, Professor Arif Ahmed, who will sit on the board of the OfS.

The Department for Education has referred to Professor Ahmed's appointment as "a huge step forward" in the protection of the right to free speech in university life.

Professor Ahmed lectures in philosophy at the University of Cambridge. He takes an empiricist outlook in his work which focuses on "questions in metaphysics, the theory of rational choice and philosophy of religion".

He has articulated his clear support for free speech and academic freedom. In his view, they "are vital to the core purpose of universities and colleges. They are not partisan values. They are also fundamental to our civilisation". In other words, the implication is that free speech is important for the functionality of wider civil society, and not merely the university.

The promotion of free speech

However, the Act goes beyond merely requiring universities to quietly respect free speech and academic freedom. Universities will also be required to promote the value of lawful free speech and academic freedom for students, university intellectuals and academic staff at higher education providers.

Specifically, the Act states that this responsibility pertains to the "governing body of a registered higher education provider". So presumably individual academics teaching subjects like political theory will be free to teach students about arguments against free speech. It would seem contradictory if they were not.

Even so, this requirement could be interpreted as a controversial one. It is one thing for the state to require universities to protect and respect free speech on campus. It is another thing for the state to require the explicit promotion of free speech in law by university governing bodies. Moreover, does the protection of free speech on campus require that university governing bodies go out of their way to promote free speech? I'll let you decide.

Furthermore, the Act also seeks to protect the reputation of British universities as "centres of academic freedom". On this point, for those interested in foreign policy, the protection and promotion of individual freedoms in universities could constitute part of Britain's soft power in the world. That is, the power of influence and attraction Britain exercises as a nation-state.

In a recent debate in the House of Lords on Britain's role in the world, the Lord Bishop of St Albans made the link between Britain's soft power and our universities. He referred to a 2017 study which "found that 58 world leaders had been educated at British universities, compared with only 57 in America and 33 in France". Moreover, one interesting question is the extent to which the global reputation of British universities is contingent on the protection of free speech.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.